Now, more precise dates, reported last month in Earth and Planetary Science Letters (EPSL) and in November 2022 in Science Advances, show the eruptions preceded the Snowball Earth event by 1 million to 2 million years. The lag points to a particular way the fire could have triggered the ice: through a chemical alteration of the fresh volcanic rocks known as weathering, which sucks carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere, turning down the planetary thermostat. The studies highlight the power of weathering as a key driver behind shifts in Earth's climate, and how components of the planet as disparate as rocks and the atmosphere are inextricably linked, says EPSL study co-author Galen Halverson, a sedimentary geologist at McGill University. "Nothing can be understood in isolation."

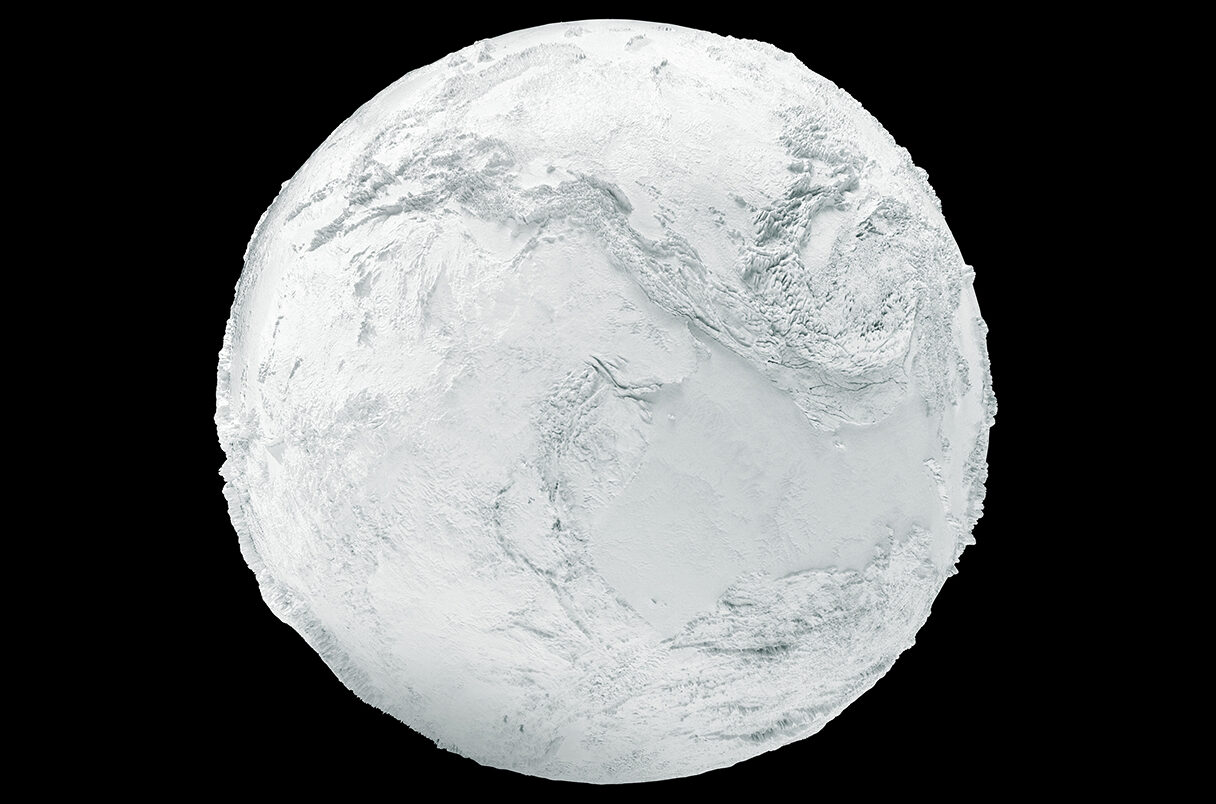

Geoscientists debating the cause of the so-called Sturtian glaciation, which lasted 57 million years, have pointed to a number of possibilities — meteorite strikes, biologic activity, shifts in Earth's orbit, and more.

Comment: That 'more' that caused 'Snowball Earth' is likely to be our sun's twin: Volcanoes, Earthquakes And The 3,600 Year Comet Cycle

But recent studies have zeroed in on one of the largest volcanic outbursts ever, preserved today across northern Canada in what's called the Franklin large igneous province (LIP). The eruptions spewed lava across an area at least the size of Argentina — and perhaps bigger than China.

Volcanism can trigger cooling in two main ways. In one, eruptions release sulfur-rich gases, which form aerosols that block sunlight and cool the planet. A section of the Franklin lava likely even burst through rocks full of sulfur-rich minerals that could have supercharged the plumes. The other mechanism is weathering. Lava rocks are particularly susceptible to the reactions, in which CO2 in rainwater reacts with the rocks, ultimately forming minerals that precipitate in the ocean.

"The difference between all these proposals is the timescales on which they happen," says Judy Pu, lead author of the Science Advances study at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Sulfur aerosols, for example, only linger in the atmosphere for months to years. Weathering, however, is much slower, requiring 1 million to 2 million years before the cooling effects peak.

Yet until recently, the estimated timing for the Franklin LIP spanned more than 10 million years, making it impossible to discern which of the two mechanisms could have been the trigger. Improvements in dating — and the two teams' sheer determination to recover rare minerals to date — are helping finally pin down the timing. "Everything starts with good ages," says Ashley Gumsley, a geologist specializing in LIPs at the University of Silesia in Katowice who was not part of the study teams.

By measuring the ratios of trace amounts of uranium and lead trapped in tiny crystals of the mineral zircon — and knowing how fast uranium decays to lead — the teams discovered that the Franklin LIP formed in just 2 million years or so, much faster than most previous estimates. And the primary pulse of volcanism happened 1 million to 2 million years before Snowball Earth, which has been dated through analysis of rocks scoured up by glaciers and eventually deposited in the ocean.

That's exactly the sort of time frame required for weathering to cause the cooling. "They're just stunning the extent to which [the dates] all line up," Halverson says. Additional analysis by Pu and her colleagues suggest the Franklin LIP formed a broad volcanic highland that would have been battered by wind and water, speeding up the weathering.

Pu says other factors may have dialed up the weathering enough to cause a Snowball Earth event. For starters, all of Earth's landmasses at the time were located near the equator, where temperatures were warm and rain frequently pelted the surface. The floods of lava also emerged during the breakup of the Rodinia supercontinent, which exposed fresh rocky surfaces to weathering and may have already begun to cool the global climate. And Gumsley says other large eruptions probably took place at this time in Siberia, China, Africa, and Antarctica, adding to the overall weathering effect.

Case closed? Not for Harvard University geologist emeritus Paul Hoffman, a coauthor on the Science Advances study who led much of the early work on Snowball Earth. Even if the timing of the Franklin LIP has improved, that of the global glaciation remains slightly uncertain, he says. Forming the ice-scoured rock that marks the start of the episode requires the flow of thick ice at sea level, a process that may not have started until several hundred thousand years after the oceans froze over.

Other Snowball periods remain mysterious. Some 650 million years ago, not long after the Sturtian glaciation, the planet plunged into another deep freeze — but no volcanic outburst preceded it, notes Linda Sohl, a paleoclimatologist at Columbia University who was not part of the study teams. Still, Halverson says weathering may have been a key factor then, too, because all the scouring by glaciers during the earlier Snowball would have exposed fresh rock.

For the Sturtian glaciation at least, the case for a weathering trigger has grown, Sohl says. "In the very least, a revisit with weathering models seems in order," she says. "The snowball glaciations are such fascinating events that are going to keep all of us quite busy for years to come."

doi: 10.1126/science.adj7226

A version of this story appeared in Science, Vol 381, Issue 6654.Download PDF

Reader Comments

Should anyone out there wish to do the same one will find a unnerving pattern where historical catastrophic events do align to such an arrival of said Planet ( our Sun's Twin )

Academia has done a brilliant job of pulling the proverbial wool over everyone's eyes, problem is, they can't this time around ( Planet X is now over due )

I believe our star has its own binary a dead or dying red or brown star, with 4-6 planets in tow( aside from being part of the multi star system orbiting Sirius). However i believe the time span beween its(red/brown dwarf) "arrival" is closer to the 11,000 year mark www.nova.org/~sol/solcom/x-objects

Which also times out exactly when our perpendicular orbit to the milky way passes "through" the milky ways plasma field. Twice during our systems orbit. Each passing " resets or flips" the earths magnetic poles. 11,000 years of sun rising in east, 11,000 yrs of sun rising in west.

More [Link]

[Link]

Tiamat was struck by ? Our binary? An Rogue object? Whatever hit it, destroyed part and sent the huge remaining chunk on an orbit 70° or so off the elliptical plane of our system

I think Hercolobus is the remains of Tiamat

All this stuff ties itself together when presented alongside all these theories

imo

But, im just a carpenter who enjoys amature astronomy. So what do i know

Fun to think about though. It sure beats whats on "the news"

I appreciate how , here on sott, we can post "crazy, outlandish" stuff and not be ridiculed. Sure i sound crazy. So does every "scientist" with a microphone or podcast. Great, intelligent, independent, informative, often humorous info an perspectives in the comments sections of sott.

However the last ice age "ended" some 11,000 odd years ago ( even though the earth is still coming out of the last, current declining ice age) is it a coincidence that the roughly 11-13000 yr cycle started or ended with the last ice age, 11,000 yrs ago?

We are indeed approaching one half of the climactic events our ancestors knew well about the orbit of our system. Which is why i believe all forms of bipods took shelter "below ground" for generations. As our system passes through these areas of space the earth gets pelted by cosmic rad, cosmic particles, meteor, asteroid, electromagnetism blah blah blah

These areas an objects cause sickness, mental disorder, confusion, navigation an migratory issues with animals. Massive planetary , solar, system wide upheaval,

I believe the "ancients" knew of this an built henges an monuments ( just one of giza pyramids true funstions, the other being a power source)) to track sirius and the progression of our systems orbit of sirius, through space, the plane of the milky way (twice) , the dust/particle field created by the milky way devouring our TRUE galaxy. The Saggirarius Dwarf Galaxy/ Nebula

imo

I also believe all these great minds throughout history were partially correct.

Its the marvel of the worldwideweb that allows all this "different" info from "different" sciences and arts and times to be made available in one convienient location. Most of this "stuff" ties together when overlaid, compared and analized together. People throughout history have been trying to prove their point or narratve. Never realizing they were just discussing one part of the whole engineered design of our multiverse.

it's getting late and I've somethings to close down, plus Earth is now expecting a significant solar Storm for the 18th with solar winds upto 700km/sec, so things are getting interesting.

WN3.

Thank you for your sharing and consideration.

Have a wonderful day!

Earth's history illustrates one thing quite clearly, that past civilisations capitalised on the remains of previous occupations, they could only do so because such previous inhabitants were removed from their homesteads by a cataclysmic event, Machu Picchu illustrates this perfectly.

So the remains of previous civilisations do give an indication that something untoward happened, the Pyramids of Giza do this as the Pyramids are sat on monolithic stonework.

I will continue this post as time once again is against me, and I'll try next time to demonstrate time lines.

WN3

I will leave it here as time is yet again running short but will continue my journey back in time.