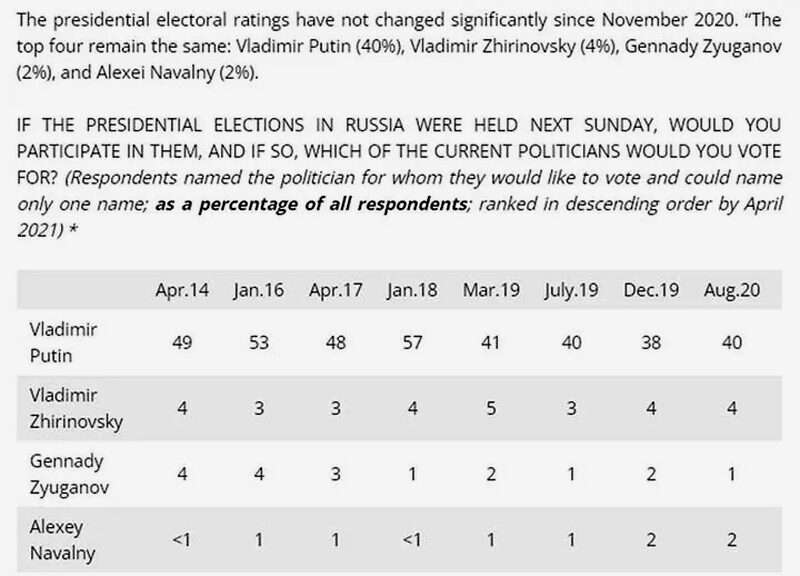

The Oscar-winning 2022 documentary film Navalny tells the story of the opposition figure who has become the West's favorite Russian activist. Despite having garnered the support of about 2% of Russian voters, according to the polling firm Levada, Alexei Navalny is presented in the film as a national hero whose anti-corruption work made him such a threat to Vladimir Putin that he had to be targeted for elimination.

The film's authors are Canadian Daniel Roher, who admits to having never visited Russia or speaking Russian; Bulgarian Christo Grozev of Bellingcat, an "open source" media organization openly hostile to the Russian government, and which acknowledges financing by governments of the US, UK and EU. The production team also includes the Russian opposition activist Maria Pevchikh, who has worked for Navalny's organization but has lived mostly outside Russia since 2006 and in 2019 obtained a British passport. CNN and Der Spiegel, which have put their names on the findings put forward by the film, acknowledge they collaborated on an investigation with Bellingcat. This fact severely undercuts the film's credibility as an independent production.

The film's protagonist, Navalny, boasts strong ties to Washington. In 2010, Navalny graduated from the Yale Maurice Greenberg World Fellowship, which hosts US-backed opposition figures from around the world and is named for the CIA-tied former CEO of the financial firm AIG. The first program director of the Yale World Fellows was Dan Esty, energy and environmental policy adviser for the 2008 Obama campaign. Esty said the goal of the program was "training leaders."

When Navalny returned from the US to Russia, he launched an anti-corruption campaign effusively endorsed by then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. Navalny is also allied with exiled oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky, who was jailed for ten years for documented tax evasion using offshore shell company transfer pricing to launder profits of oil company Yukos, which he obtained through the infamous corrupt loans for shares deal in the Boris Yeltsin years.

Despite his reputation as an anti-corruption crusader, Navalny has faced his own criminal fraud problem, along with his brother Oleg.

In 2008, when the state-owned Russian Post decided to end collecting parcels from clients' distribution centers, Oleg Navalny (Alexei's brother) persuaded several companies to shift to the privately owned Chief Subscription Agency (GPA). Oleg did not reveal it was a company that he, Alexei and their parents had just set up in the tax haven of Cyprus.

Later, Yves Rocher Vostok of the famed French cosmetics firm sued the Navalny's on the grounds that they deprived him of free choice and did not inform him that GPA was using subcontractors which charged around half as much as they paid it, while the Navalny cutout kept the difference as profit. A court gave Alexei a suspended sentence of 3.5 years and his brother a prison sentence of the same term.

The European Court on Human Rights found, "By all accounts, GPA was set up for profit-making purposes and the applicants thus pursued the same goal as any other founder of a commercial entity." So, in spite of questionable insider tricks, the European court deemed it no crime, because that is how business is done. Yet the insider trading scandal was nonetheless a black mark on the reputation of the famed anti-corruption crusader.

Although the plaintiff, Yves Rocher, was part of a French company which sued for damages in France, Western media depicted the trial as a sham instigated by President Vladimir Putin and failed to report the full details of the case. Navalny's violation of his parole by refusing to return to Russia as soon as he had recovered his health in Germany formed the basis for his arrest on January 17, 2021, and his subsequent court sentence to prison, where he remains. It is highly unlikely that US court rules for parole violations would allow any different treatment.

By this time, Navalny also become a player in America's Russiagate operation. He published a video in 2018 claiming that Russian businessman Oleg Deripaska acted as a messenger between President Donald Trump's ex-campaign chief Paul Manafort and a top Kremlin foreign policy official.

Navalny's lone source was a Belarusian escort named Nastya Rybka, who has attempted to earn money by auctioning off a photo of herself sitting on Trump's face. Rybka issued her allegations against Deripaska while detained in Thailand, where she had been posing as a "sex coach" as part of a notorious prostitution ring. She had offered the US government damaging info on Trump and Russia in exchange for her freedom, but wound up pleading guilty to prostitution charges in Thailand.

As even the UK's Guardian acknowledged, Navalny never produced proof to support the incendiary claims supplied to him by the desperate escort. Deripaska, for his part, called the allegations "scandalous and mendacious," and successfully sued Rybka.

Navalny has not corrected his video on Deripaska and Trump. This confirms not only his standard for truthfulness in documentary work - or lack thereof - but also highlights the kinds of alliances he has forged inside the US.

Indeed, Navalny appeared far more popular within US government circles than among the Russian public.

During the Russian regional election campaign of 2020, Navalny claimed popular support, though a poll by the respected Levada agency showed him drawing no more than 2% among Russians countrywide. His base remained among a slice of young Russians in urban centers.

Doctors in Omsk said Navalny issued a "main working diagnosis" for the opposition figure's illness on August 21. "Today we have [several] working diagnoses. Among these working diagnoses, the main one that we are most inclined towards is a carbohydrate deficiency, that is, a metabolic disease. This could have been caused by a sharp drop in blood sugar on the plane, which caused a loss of consciousness," chief physician Alexander Murakhovsky stated.

According to IntelliNews, published in Berlin, "Navalny said himself that he suffered from diabetes in 2019."

While subsequent medical analyses by Western doctors disputed Murakhovsky's claim, the Western-backed Russian media outlet Meduza noted that it is possible to lose consciousness as a result of this condition: "The brain consumes a significant amount of the glucose that comes from food or is produced in the body, so a sharp decrease in the amount of glucose in the bloodstream can result in the brain no longer having enough energy to function," Meduza wrote.

The Oscar-winning documentary film starts with Navalny returning to Russia after several months in Germany and then relies on flashbacks.

Navalny on a campaign stop in Novosibirsk on August 18, 2020, before he travelled on to Tomsk. He complains about the absence of police trailing him, which would have confirmed his threat to the government.

In one of the flashback scenes, Navalny makes a candid admission that is worth noting. He complains that he had gone to Siberia to make a film about local corruption. He then states, "I expected a lot of people who'd try to prevent our filming, confiscate our cameras or just break our cameras or try to beat us. I expected that sort of things and I was very surprised, like, 'Why is nobody here? Why is there kind of... I even have this strange feeling like, like a lack of respect. Like, seriously? I'm here and where is my police?'"

This is a tacit admission from Navalny that he was far less important than he, the Western press, and the filmmakers have claimed he was. It casts doubt on the premise laid out at the beginning of the Navalny film that the president of Russia, Vladimir Putin, was out to personally destroy him, and had sent hitmen to Tomsk.

The film is also marred by several deceptive claims. One arrives during long section about Bellingcat's Christo Grozev buying travel and contact data on the darknet to find the names and phone numbers of Federal Security Service (FSB) agents who had been traveling on planes to Siberia in August of 2020. There is no way to verify that data Grozev and Bellingcat marshaled to identify the supposed agents that targeted Navalny is in any way credible. Their claims would have almost certainly fallen apart if put forward by prosecutors in a US court. In fact, as CNN noted on December 14, 2020, "CNN cannot confirm with certainty that it was the unit based at Akademika Vargi Street that poisoned Navalny with Novichok on the night of August 19."

The great phone call hoax

The real test of the veracity of the film - the big reveal that is intended to confirm its devastating thesis - comes in the form of a hoax telephone call between Navalny and his supposed pursuers.

Those who made the film clearly understand how to manipulate audiences. In an apparent bid to make viewers feel like witnesses of an elaborate trick that exposes the malign intentions of the bad guys, Navalny is showing putting on a hidden body mic. But why? He is not going anywhere to secretly record an FSB agent. Only his own team is in the room. The real recording microphone, a sound boom, is off camera, where the film audience can not see it.

Navalny then "calls" three supposed FSB agents. This is a setup for a veracity diversion, a factoid - that's a seeming truth disguising a fake. We can be sure of this now because he says to each of the agents, "I am Navalny; why do you want to kill me?" And the supposed spies - or whoever they are - hang up. This performance is clearly aimed at convincing the audience that the FSB was being telephoned.

But then there's his pièce de résistance, the interview with "the scientist" whom Grozev tells Navalny to call, because he will be more likely to talk than the regular FSB agents.

Impersonating a Russian security official, Navalny declares (as translated in the Bellingcat video below), "Konstantin Borisovich, hello my name is Ustinov Maxim Sergeyevich. I am Nikolay Platonovich's assistant." He continues, "I need ten minutes of your time ...will probably ask you later for a report ...but I am now making a report for Nikolay Platonovich ... what went wrong with us in Tomsk...why did the Navalny operation fail?"

According to Bellingcat, the real Kudryavtsev worked at the Ministry of Defense biological security research center and is a specialist in chemical and biological weapons. He is supposedly not so stupid.

But the unusally talkative "Konstantin" proceeds to spill the beans: "I would rate the job as well done. We did it just as planned, the way we rehearsed it many times. But when the flight made an emergency landing the situation changed, not in our favor.... The medics on the ground acted right away. They injected him with an antidote of some sort. So it seems the dose was underestimated. Our calculations were good, we even applied extra."

How conceivable is it that the filmmakers, Navalny and Bellingcat would get exactly what they needed from the source they targeted?

Like the rest of Western media, CNN highlighted the phone call without a shred of critical scrutiny:

Navalny was questioned by the Berlin Staatsanwaltschaft (District Attorney) on December 17, 2020. Did he tell them about the phone call to Konstantin Kudryavtsev, which allegedly took place on December 14?

The office confirmed the interrogation took place, but when I sent the Berlin prosecutor a link to Navalny's claims about the December 14th "call" three days earlier, a spokesman said they could not comment further.

There are key clues to the film's fabrications. They deal with dates and timing which are not subject to dispute: the qualities of Novichok, the date of Kudryavstev's "cleaning" in Omsk, the timing of lab reports and the date of the phone calls.

The shifting Novichok delivery devices

Yulia Navalnaya says in the film, "After a week I was unexpectedly called to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs." As the Navalny group arrived August 22, that would have been about August 29th. "They said we have discovered that your husband was poisoned with an agent from the Novichok group."

It was not the Charité lab that found this. The German Government announced not one, but two weeks after the group's arrival, that a laboratory of the German Armed Forces had identified a nerve agent from the Novichok group in blood samples collected after the patient's admission to Charité.

Unlike the civilian doctors, who had not found Novichok, the military lab would not release details of its tests. There was no toxicology report, no name of the expert in charge of the testing and of the interpretation of the results, no name and formula of the chemical compound of the "Novichok group." The Germans refused to send any medical or toxicological evidence they claimed to substantiate the attempted homicide to Moscow prosecutors investigating the crime. From then on, by hearsay and without evidence, Western media concluded that Putin personally ordered the poisoning of Navalny.

Second, there is the issue of Navalny's underpants. Navalny, his wife Yulia, his assistant Pevchikh, his press spokesman, others in his group, and the reporters acting as their de facto stenographers had claimed until that moment that the mechanism for delivering the Novichok had been a tea cup at the airport café. They then claimed a water bottle in the Tomsk hotel room was used to poison him.

Navalny's wife repeatedly told the press that Pevchikh had filmed the removal of the hotel room water bottles, taken them secretly to Omsk, then loaded them on the medevac flight to Berlin in the luggage of one of the medevac crew, and delivered them from the German ambulance into the Berlin hospital by hand. But then, after four months had elapsed, the story changed again, with Navalny's underpants taking center stage as the delivery mechanism.

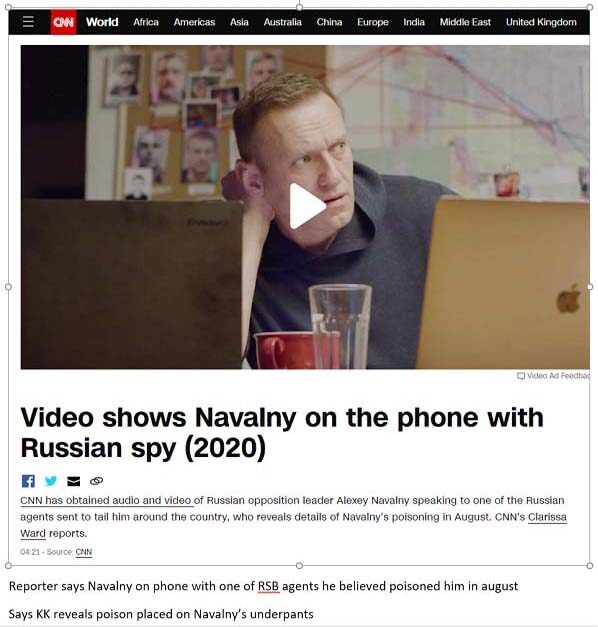

A report by CNN's Clarissa Ward not featured in the Navanly film claims the poison was applied to the underpants "across the seams" at the button flap. According to toxicologists consulted by CNN, "it appears the assailants used a solid form of the nerve agent." So was the FSB counting on Navalny not to notice or feel moisture as he dressed? Was the poison then in direct contact with his body?

On the plane, Navalny fell ill, and the pilot diverted to Omsk, where he was transferred to a hospital. The calculated lethality of the dose should have been fatal after the onset of symptoms. However, the first symptoms appeared only after several hours, and they remained non-lethal for at least one more hour between Navalny went to the toilet cabin on his flight and his reaching Omsk hospital.

On the timing of Kudryavtsev's trip and "cleaning"

CNN declares that "Kudryavtsev" flies from Moscow to Omsk on August 25, five days after the event, to take possession of Navalny's clothes and "clean" them. It displays a visual of a flight from Moscow. But the FSB would have known of the diversion to Omsk August 20. Would it have waited five days to send an agent there?

The film script places Kudryavtsev in Tomsk for the job. At least he knows the details of where the Novichok was placed. He says, "We did it as planned."

The film "Kudryavtsev" voice says, "When we arrived [in Omsk], they gave [the underpants] to us, the local Omsk guys brought [them] with the police." Did any police fall ill?

"Kudryavstev" says, "When we finished working on them everything was clean." He explains that solutions were applied, "so that there were no traces left on the clothes." CNN, in its video, has "Kudryavtsev" saying that he also cleaned Navalny's pants, not mentioned in the film. Alexei is shown in Berlin holding the underpants. Did the Omsk police ship the "decontaminated" item to Germany?

Conflicting reports, suspicious timing expose more holes in the story

Conflicting reports raise questions about whether Navalny's underpants remained in Omsk.

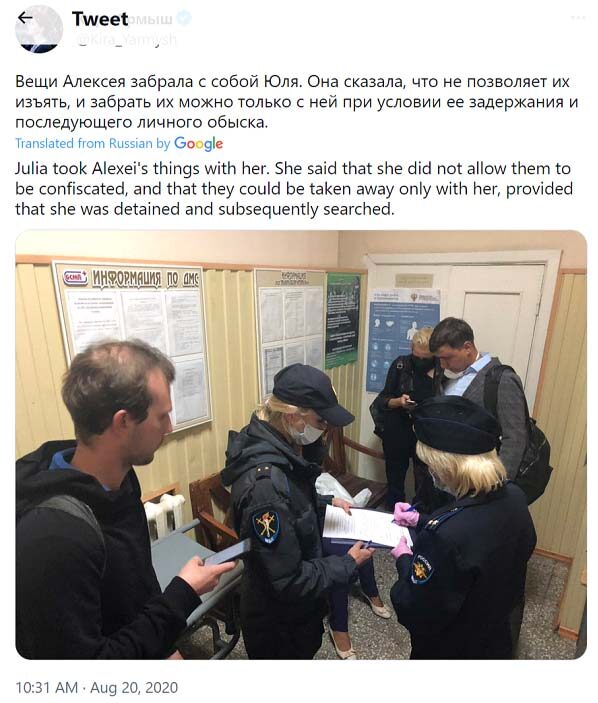

Navalny's press secretary Kira Yarmysh posted a tweet August 20, 2020 with the text: "Julia took Alexei's things with her. She said that she did not allow them to be confiscated." However, The Guardian reported on September 21 that Navalny "demanded that Moscow return his clothes."

Ronald Thomas West, a self-identified US Special Forces veteran working in Europe, raised more questions about the call's timing:

"The poisoning happened on 20 August, the 'hoax call' is made on 14 December, and released by Bellingcat on 21 December. Now, wait a minute. The context of the call, a desperate demand for answers of what went wrong (why Navalny didn't die) for a report to higher up authority, is something you would expect within the first 48 hours, not nearly three months later. By the time this call was made, that dust should have settled and been vacuumed up by Russia's intelligence services. Everyone would have been debriefed by this time, including the target of the hoax call."The film supports a bogus analysis of Russian politics

An unidentified woman appears in the Oscar-winning documentary to declare,

"What to do with Navalny presents a conundrum for the Kremlin, let him go and risk looking weak, or lock him up, knowing it could turn him into a political martyr." A US broadcast reporter is also featured stating: "Unexpectedly, Vladimir Putin has a genuine challenger. More than any other opposition figure in Russia, Alexei Navalny gets ordinary people out to protest."Eric Kraus, a French financial strategist working in Moscow since 1997, offered a different view of the so-called opposition leader:

"Mr. Navalny was always a minor factor in Russia. He had a hard-core supporter base — Western-aspiring young people in Moscow and St. Petersburg — the 'Facebook Generation.' He was never much loved out in the sticks and could never have polled beyond 7% nationwide, even before the war. Ordinary Russians now increasingly see the West as the enemy. Navalny is seen as the agent of forces seeking to break or constrain Russia. Now, he would get closer to 2%."(Kraus has been cited as an expert by the New York Times, among other Western outlets.)

Kraus said,

"He is the supreme political opportunist. In Moscow, speaking in English to an audience of Western fund managers and journalists, it is the squeaky clean, liberal Navalny. Full of free markets, diversity, and social justice. Hearing him a few months later out in Siberia, speaking in Russian, one encounters an entirely different animal - fiercely nationalistic, angry and somewhat racist. There, his slogan is 'kick out the thieves,' but especially 'Russia for the ethnic Russians' - anyone without Slavic blood, especially immigrants from the Caucuses, are second-class citizens."Below is a Navalny-produced video in which he calls for migrants to Russia to be treated like cockroaches.

The Council on Foreign Relations threatens to strip me of membership for questioning "Navalny" filmmakers

As a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, I was invited to a November 9, 2022 "Navalny" screening by CNN at 30 Hudson Yards in Manhattan. Timothy Frye, professor of post-Soviet foreign policy at Columbia University, moderated the discussion with the filmmakers after the screening.

During Q&A, I asked the filmmakers a question that went as follows:

"My name is Lucy Komisar, and I'm an investigative journalist. I want to delve more into the Kudryavtsev story. Mr. Navalny was questioned by the prosecutor in Berlin on December 17th. And three days earlier was the phone call with Kudryavtsev. Did he tell the prosecutor about the phone call which I assume they would have to check the authenticity of, and what did they determine about him? He claims on the phone call he examined these things on August 25 .... But on August 20 ...."[In fact,"Kudryavtsev" didn't give the August 25th date, Bellingcat did.]

I was then interrupted by Professor Frye, who attempted to shut down the event with a convoluted comment: "This is all on the issue and nobody else, which is that after we stop in 10 minutes. There will be drinks. Okay, that's...."

I interjected,

"The point is the press secretary said Alexei [Navalny's] things were taken by Yulia before that, and she didn't allow them to be seized. So how could they have been examined by this man after they were already taken away? And finally, the Berlin doctor said they didn't detect any poisoning in Navalny's blood, but two weeks later it was the German Armed Forces laboratory that said, yes.Christo Grozev of Bellingcat responded indignantly: "Almost none of this was actually correct and including the sequence of events. I mean, this was reactive and FSB officer on screen, on recording that I made on my phone confessing to all of that."

So, all these things I think are contradictory and I would like to know the facts of why these contradictions exist."

"You said it's him," I said, "but we don't know it's him."

"Well, I think the rest of the world knows and now okay," Grozev assured the audience before suggesting I was somehow an agent of the Russian government: "Be nice to know who you work for because...."

"Oh, is this gonna be a [Joe] McCarthy question now?" I asked him.

Once again, Prof. Frye moved the end the discussion: "Well, thank you, Tim, Maria, Christo and Daniel. Thanks also to CNN HBO Max Warner Brothers Pictures ... ."

He invited us all to drinks at Milos, a trendy restaurant inside the complex. I went to the reception and asked Roher if I could interview him. He angrily refused and accused me of working for the Russians.

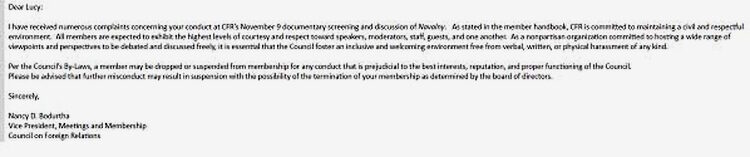

Days later, on November 17, I received an email from Nancy Bodurtha, the Vice President of Meetings and Membership for the Council on Foreign Relations. She had apparently received complaints about my conduct at the screening. Her email threatened me with the termination of my membership for asking pointed questions of the makers of Navalny.

"Per the Council's By-Laws," I was informed, "a member may be dropped or suspended from membership for any conduct that is prejudicial to the best interests, reputation, and proper functioning of the Council."

Please be advised that further misconduct may result in suspension with the possibility of the termination of your membership as determined by the board of directors."

A version of this piece was originally published at The Komisar Scoop.

Grayzone Editor's note: The Grayzone has amended this article, removing two claims that were not properly sourced in the article originally published by The Komisar Scoop, and replacing one regarding Navalny's health condition with articles sourced to Intellinews and the Western-backed Russian opposition outlet, Meduza. Lucy Komisar's article also incorrectly stated that Daniel Roher had not previously produced a documentary feature. Roher has previously produced Once Were Brothers.

Lucy Komisar is an award-winning investigative journalist. Her website is The Komisar Scoop

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter