England's chief medial officer has claimed the nation faces a rising death toll from heart disease and cancer cases due to pleas to protect the NHS. Knock-on effects of dealing with Covid, which saw thousands of routine treatments and appointments delayed, will also fuel a surge in excess deaths.

The comments came from a 'technical report' published on the pandemic, advising health chiefs in the future on how to deal with similarly disruptive viral threats.

The report was also authored by Sir Patrick Vallance who, with Sir Chris, became a household name during the pandemic, appearing next to then-Prime Minister Boris Johnson during tense Downing Street briefings to talk the nation through the crisis.

In one section, the team warned their successors that the 'extraordinary' speed at which vaccines were developed could lull politicians in the future into a false sense of security.

Sir Chris and Sir Patrick said testing shortages in the 'critical months' at the start of the outbreak hampered efforts to track the virus. 'This may well be a repeated problem in future pandemics', they wrote.

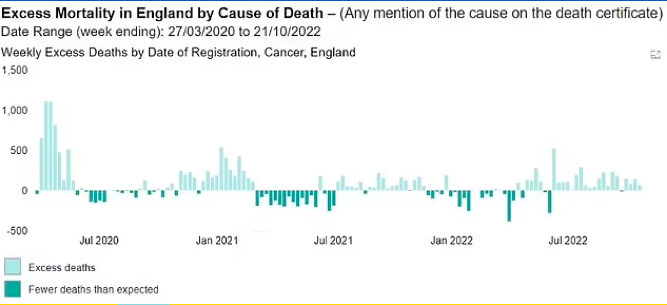

Hundreds more Britons than expected are currently dying each week, despite the worst of the pandemic being over.

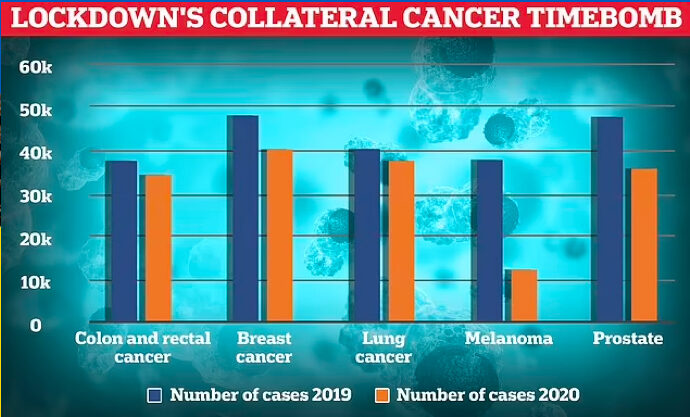

Experts say the collateral effects of Covid on treating cancer are to blame for a big proportion of those.

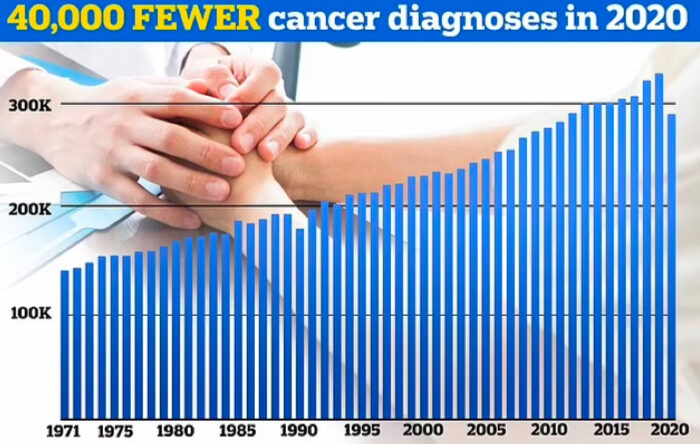

Cancer checks effectively ground to a halt during the pandemic and patients faced delays for treatment as oncologists were put on Covid wards and patients were told to stay at home to protect the NHS.

And thousands fewer people than expected have started cancer treatment since the pandemic began — despite NHS performance recovering slightly this summer.

The report also touched on the controversial policy on discharging potential Covid positive residents into care homes during the pandemic. Campaigners have stated the decision played a role in the deaths of thousands of elderly Britons.

In the report, Sir Chris and Sir Patrick called dealing with care homes 'some of the most complex' decisions of the pandemic. Officials tried to slow the spread of the virus without producing staff shortages in care and leaving vulnerable residents isolated. Despite criticism of the policy, Sir Chris and Sir Patrick wrote that that 'does not appear to have been the dominant way in which Covid entered most care homes'.

Their report also hints at tensions with politicians, describing a 'craving for certainty' at a time when scientists were still grappling with the at-the-time unknown virus. They wrote:

'Policymakers are often comforted by being able to see a line on a graph purporting to show what will happen under a given policy, but modelling will never be able to precisely predict the future.The pair acknowledge the downsides of lockdowns and school closures, saying they were always a matter of the 'least bad option'.

'Delays in drugs or vaccines being available, or the emergence of a variant with greater transmissibility, vaccine escape or leading to more severe disease, could result in longer deployment of non-pharmaceutical intervention.'

But they admitted the policy risked having 'lasting effects on children's education, developmental and life chances'.

The shift to online GP appointments helped to reduce transmission but a reluctance to see a doctor among some patients resulted in 'significant unmet need', which could lead to further deaths and illness. They wrote:

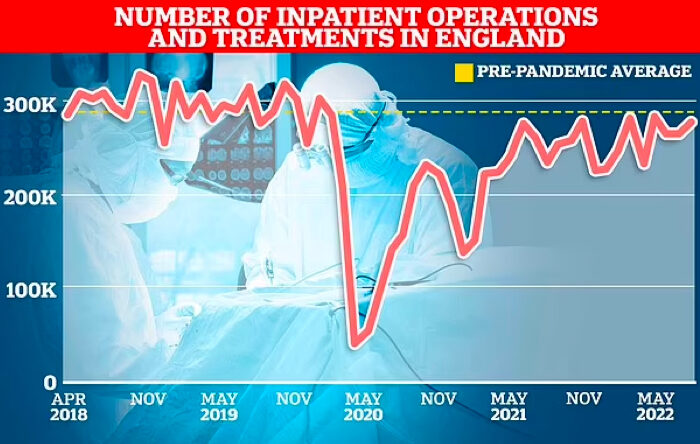

'There is little doubt that delays in presentation, reductions in secondary prevention (such as statins and antihypertensives), postponement of elective and semi-elective care and screening will have led to later and more severe presentation of non-Covid illness. The combined effect of this will likely lead to a prolonged period of non-Covid excess mortality and morbidity after the worst period of the pandemic is over.'Covid famously led to the cancellation thousands of elective operations and diagnostic tests due to how the virus disrupted the health system.

The public was told to help protect the NHS, and while medics consistently urged people to come forward if they had worrying symptoms, many stayed away.

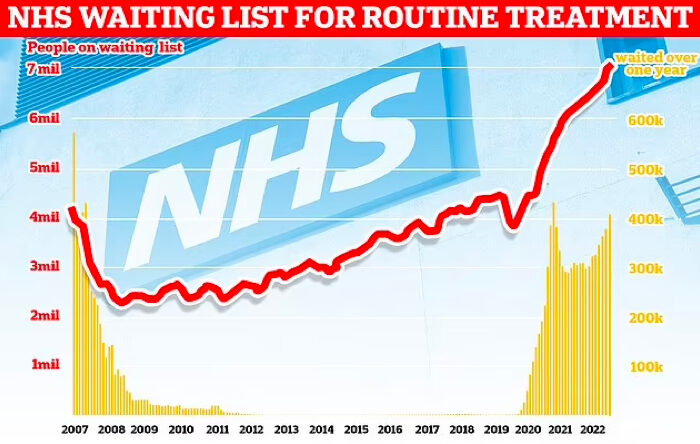

The NHS has still failed to recover from the pandemic.

Official figures show 7.1 million people in England waiting for routine hospital treatment, such as hip and knee operations, by the end of September, the latest available data.

This figure also includes more than 400,000 people who have been waiting for over a year, often in pain and discomfort.

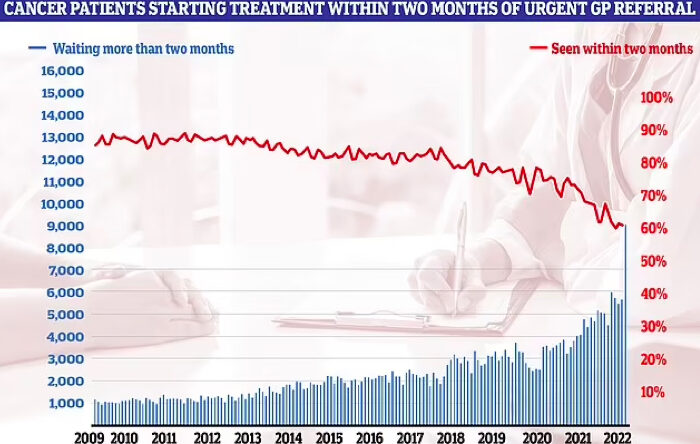

NHS cancer care, which has struggled to reach targets for years, has further floundered to a record low post-pandemic.

The latest data shows just 60.5 per cent of patients started cancer treatment within two months of being referred for chemotherapy or radiotherapy. The figure is down from 61.9 per cent one month earlier and is the lowest ever recorded in records going back to October 2009.

The NHS states 85 per cent of patients should start treatment within this timeframe.

Poor NHS performance comes as the health service prepares for a grim winter over fears of a 'tripledemic' of Covid, flu, and other seasonal infections exacerbating health service delays.

Integral part of the plan. Thank Bill and co.

Gaslighting much!? They we’re the WORST options to take!

Up from last year’s twindemic. Mmmm, I wonder what next year will be?

But fear of a tripledemic must be pumped as guess what they’re working on now? [Link]

Or have been working on but have only just admitted it, because this was the plan all along.