That faith, in evolution as a fact, is so strong that I'm sure many have already left this page and are searching for the unsubscribe option for this Substack. The same sort of reaction someone believing the mRNA 'vaccine' is safe and effective would have to an 'anti-vaxer'. "What the hell is Winston on about now! He's lost the plot and deluded!" The concept is so deeply embedded into our psyche that to oppose it can elicit a visceral retort or religiously zealous combativeness.

But for those of you who have not yet unsubscribed and headed off to a better Citizen, the planet Barsoom, or to look for a cat, or be intrigued by political evil (reciprocal links fully expected guys ;-) ), let me assure you our journey will be a fascinating one through the complexities of our genome, space, philosophy, geology and so much more. Yes, I intend this series "A Strong Delusion" to be somewhat extended, as it touches on so many intriguing aspects of our existence.

Are you up for it?

I want to kick off this series by looking at our genome and a concept known as genetic entropy - a concept that flies directly in the face of Darwinian evolution (which supposes the genome increases in complexity and order over time) but is in agreement with classical physics and our common sense observations of the material world. It will be a bit of a journey as there is some groundwork required for those not familiar with genetics - but don't worry - I'll write in layman's terms and use lots of metaphor so you can easily get the concepts without having a masters degree in biology. I'll start that in the next instalment of this series.

But first I wanted to just share something that has been motivating me for some time now around this topic. Not just because of the psycho-social-spiritual implications, but because it's so frustrating that no one in Biology 101 even thinks to question the beginning of the so called evolutionary tree of life. Apparently the biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky said, "Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution." Yet when I consider the beginnings of evolutionary history, for me, "nothing in biology makes sense in the light of evolution." Yet just about every mainstream scientist and philosopher, even my beloved Iain McGilchrist, are completely convinced that evolution must be the truth and anything else is a fairy tail.

But let me get to the point quickly before I launch into a rant...

Acclaimed neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux, whom I deeply respect for his work on the neuroscience of emotions, wrote a book called The Deep History of Ourselves: The Four-Billion-Year Story of How We Got Conscious Brains. In that book he explains the beginning of the tree of life - LUCA (Last Universal Common Ancestor) which was the first cell, or cells, derived from "protocells", which were even earlier bits of RNA, DNA, and proteins floating around in the water before the first cell.

But where did the protocell RNA or DNA come from?

LeDoux cites an experiment from the '50s by Stanley Miller who tried to create the building blocks of life in a test tube by heating and zapping an atmosphere of hydrogen, ammonia, and methane. He did produce some amino acids, the building blocks of proteins. But then we jump from producing a few amino acids to RNA or DNA - an incredibly complex structure even for the simplest of living things. There's no explanation for how such a structure came about.

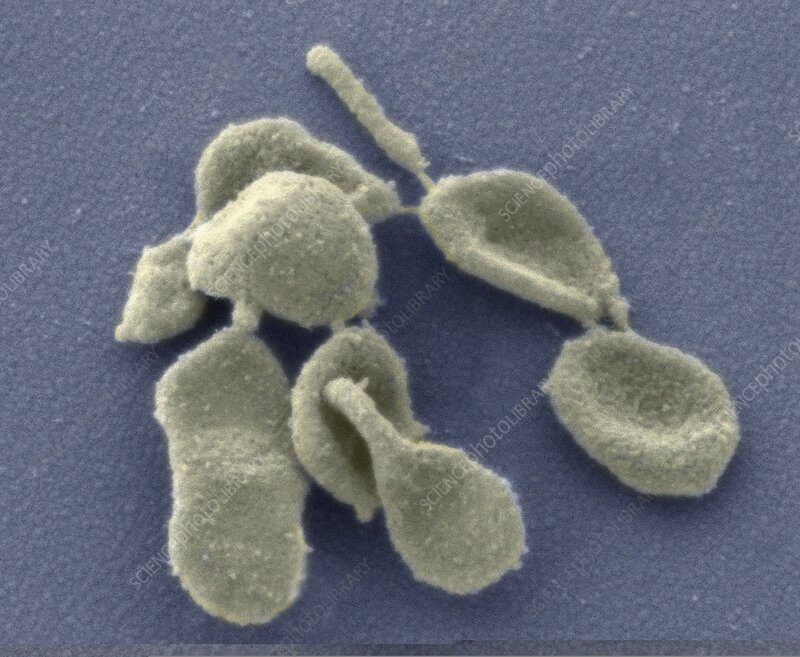

One of the simplest organism, genetically, that we know about is Mycoplasma genitalium, with 525 genes comprised of 580,070 base pairs. What are the chances this combination of genetic code came about by chance? Say you had to guess what the combination of a lock was on a highly secure vault. You have to punch in a combination of letters (a base-pair sequence) that looks a bit like this: ATCGATTGAGCTCTAGCG (this is just 9 pairs in a DNA sequence, A-T always go together and G-C always go together, you have to guess 580,070 of these pairs). But that's assuming the zapping of an atmosphere can produce enough guanine, cytosine, adenine and thymine, in close proximity for the many trials required to produce this particular sequence. But then what? Let's say you, or the random non-intelligent process of evolution, correctly guessed the right sequence to have a viable strand of DNA. What's going to happen to it? You've got a strand of free-floating DNA (just like at the beginning of the film Prometheus when the alien humanoid drinks a potion and breaks down into the water) and it needs to be encapsulated by something. It needs a cell wall, a lipid casing. There are a number of theories as to how RNA or DNA might have been encapsulated but none seem plausible nor reproducible. We've not been able to encapsulate a strand of RNA by say a foam barrier of iron sulphide (one of the theories) and observe that encapsulated RNA spring to life. But somehow we have to jump from this miracle of random sequencing of nucleic acids somehow encapsulated in something, to the first cell LUCA, to a bacteria - the complexities of it's internal components are mind boggling. (For a deep dive into cellular complexities check out Dr Jon Lieff's book The Secret Language of Cells).

In the Annual Review of Microbiology there is an article on E. coli, supposed to be a primitive, 'simple' bacteria, the authors wrote:

Even though the entire sequence of the E. coli K-12 chromosomal DNA has been known for [over] two years, we are still far from knowing all of the details of how the cell operates, lives, replicates, coordinates, and adapts to changing circumstances . . . the number of experimental journal articles on aspects of the basic biology of E. coli has increased from an average of 78 per month in 1996 to an average of 94 per month today . . . new biological information about this well-studied organism continues to roll in. New metabolic capabilities are discovered and are connected to underlying genes. There are new regulation systems, new transport systems, and more information on cellular constituents and cellular processes.Does this sound like a simple organism to you? Does it sound like something that could just come about randomly, even if, somehow, a correctly organised strand of RNA was encapsulated in some sort of membrane?

. . . but how many regulators are needed to maintain coordination of expression of the genes and correct interaction among the gene products? Regulation systems are not the same in all bacteria, and we still do not have all of the information for the regulatory networks of even one bacterial species . . . the minimal set of genes and proteins necessary for life of an independently replicating cell does not have an easy answer.

Experimentation into details of the biology of E. coli continues unabated today, and the numbers of papers published annually continues to increase . . . not all enzymes and pathways in E. coli are known . . . besides genes for unknown enzymes, we have data for enzymes that don't have genes. There are 55 enzymes of E. coli that have been isolated, purified and characterized over the years, but their genes have never been identified.

The advent of massive DNA-sequencing technology and the completion to date of [more than] 20 microbial genomes that are now available to the public have not brought us (yet) to a complete understanding of exactly how a single free-living cell functions and adapts to changing environments. (Riley, M., Serres, M.H., "Interim report on genomics of Escherichia coli" Annual Review of Microbiology, 2000 pp. 341-411.)

This is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the amount of faith one has to have to believe life sprung up randomly (the so called 'Blind Watchmaker') without any intelligent design. Next time, I'll start the series with the nature of our own genome and explore the concept of increasing complexity and functionality in theory against the demonstrable nature of entropy.

Hope you can join me.

Winston Smith is trying to understand and avoid mass psychosis. Musing about freedom, health, psychology, spirituality, and the nature of things. Suffers from totalitariophobia (fear of oppression), extremely curious, and works for The Ministry of Truth.

Why mention this, well to all intense and purpose these bits of cut up ginger bits should be dead, but there not. For written within is instructions on how to regenerate, the only thing missing is a suitable environment.

So I soak said 2 bits of ginger over night, so as to rehydrate it and it did respond by swelling. I tapped dried the bits and this afternoon I planted them in some suitable compost and they now sit on my kitchen windowsills with a plastic bag on top of each pot so as to reduce moisture loss and help maintain the temperature.

So where does this fit in with the above article?

There's a growing debate brewing regarding " evolution " and the mechanisms involved, something that's resulted in a polarised approach, with modern day followers happily discrediting Darwins work and throwing their ideological notions liken to teddies at anyone who still believes in Darwin, I do believe that Darwin has hit a nail right on the head and yes today's Darwin bashers are right too.

My ginger would have died if I hadn't interveined, I created a suitable environment for it to do its magic. I am not clever enough to understand what is now happening on a microscopic scale but I do know that as a consequence of my involvement and created environment, these ginger bits will react and establish a mature state, given time.

They will also adapt to the environment in they find themselves living in, how?

That I believe has aspects of all current and yesterday's thinking involved and one camp can claim victory.