Since the Maidan uprising in late 2013, the U.S. has taken an intense interest in Ukraine, and many of the decisions it has made seem almost designed to provoke Russia. This is not to say they definitely were - which is a matter for debate - only that it's hard to explain why else the U.S. would have made them.

American officials publicly backed the 'Revolution of Dignity' in 2014, which saw the replacement of Ukraine's pro-Russian government with one made up of pro-Western nationalists. They even helped the Maidan 'revolutionaries' behind the scenes, though to exactly what extent is not clear.

When you think about it, this is extremely provocative. Imagine if Chinese officials travelled to Canada, and publicly backed a protest movement seeking to replace Canada's government with a pro-Chinese one. Americans would be outraged.

After Ukraine's president was toppled, the U.S. had significant sway over the new regime. As the most powerful Western country, it could have said, 'We will not recognise your government unless you do X, Y and Z.' Despite this, the U.S. allowed almost a quarter of cabinet positions to go to the far-right Svoboda party - a party the EU had previously denounced as "racist, anti-Semitic and xenophobic".

Svoboda is not merely far-right, but specifically anti-Russian: the party's leader once railed against the "Moscow-Jewish mafia ruling Ukraine". How hard would it have been for the U.S. to say, 'We will recognise your government so long as no cabinet positions go to the far-right'? But they made no such demand. In fact, U.S. politicians were pictured smiling and shaking hands with Svoboda's leader - a man who, in any other context, they would have surely decried.

In the following years, the U.S. spent billions of dollars training and equipping Ukraine's armed forces. (Note that Obama initially opposed arming Ukraine, since doing so could "draw a more forceful response from Moscow".) The U.S. also began incorporating Ukraine into NATO - something it had a long-known was an absolute red line for Putin. Meanwhile, U.S. senators travelled there to give pep talks to Ukrainian soldiers.

One detail is particularly hard to explain unless you take a cynical perspective. Earlier this year, Zelensky told CNN:

"I requested them personally to say directly that we are going to accept you into NATO ... And the response was very clear: you're not going to be a NATO member, but publicly the doors will remain open."If the U.S. had no intention of letting Ukraine into NATO, why would it want Russia to think the opposite?

In the months leading up to Russia's invasion, the U.S. even encouraged Ukraine to crack down on the pro-Russian opposition. According to Zelensky's former national security adviser, the decision to shut down three pro-Russian TV stations was "conceived as a welcome gift to the Biden Administration" and was "calculated to fit in with the U.S. agenda".

One obvious motivation for U.S. policy was to "see Russia weakened", in the words of words of Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin. By getting Russia bogged down in a protracted conflict, the U.S. hoped to deplete Russia's economic resources and perhaps even foment regime change. But was there another reason?

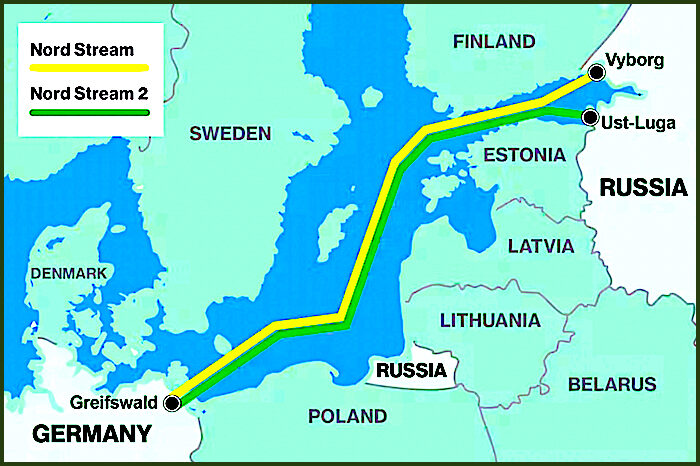

Yes, says journalist Mike Whitney: to sabotage Nord Stream 2. (This was the second pipeline built to transport gas from Russia to Germany. Originally conceived in 2011, construction did not begin until 2018, and was completed in September of 2021.) Here's the basic argument:

In a world where Germany and Russia are friends and trading partners, there is no need for US military bases, no need for expensive US-made weapons and missile systems, and no need for NATO. There's also no need to transact energy deals in US Dollars or to stockpile US Treasuries to balance accounts. Transactions between business partners can be conducted in their own currencies which is bound to precipitate a sharp decline in the value of the dollar and a dramatic shift in economic power.This is certainly a provocative theory, but is it true? I'm not aware of any direct evidence, so for the time being it should be regarded with appropriate scepticism. However, there is circumstantial evidence, and the theory is sufficiently plausible to be worth discussing.

It's no secret that the U.S. strongly opposed Nord Stream 2 (which has been dead in the water since February 22nd, when Germany pulled the plug after Russia's recognition of the two breakaway regions).

In April 2017, five European energy companies reached a deal with Gazprom concerning how the pipeline would be financed. Two months later, the U.S. slapped sanctions on Russia in an effort to thwart the project. This prompted sharp rebukes from European leaders, with the German Foreign Minister stating, "Europe's energy supply is a matter for Europe, and not for the United States of America."

Despite delays and higher costs, the project continued. Then in January 2019, the U.S. Ambassador to Germany wrote "threatening letters" to several German companies involved in the pipeline's construction, warning that they would face sanctions if they continued work on the project. This "very unusual" move was met with "incomprehension" in the German foreign office.

By July of 2021, U.S. officials had "given up on blocking the pipeline's completion" and were "scrambling to contain the damage". Under a deal signed by Washington and Berlin, the project would go ahead unless Russia attempts to "use energy as a weapon or commit further aggressive acts against Ukraine".

Over the past five years, U.S. officials have given two main reasons for their opposition to Nord Stream 2:

That it would threaten European energy security by increasing the continent's dependence on Russia; and that it would harm Ukraine by depriving that country of billions in transit fees.Yet it's widely recognised the U.S. also had self-interested motives. "By reducing access to Russian gas," writes historian Sophie Marineau, "it hoped to increase its own exports of liquefied natural gas". America produces vast quantities of gas through fracking, but has been unable to compete with Russia due to the cost of shipping gas across the Atlantic.

Two months before Russia formally recognised the two breakaway regions, the U.S. still had its sights on Nord Stream 2. As the Financial Times noted on December 8th:

"The Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline to Germany was top of the list when US officials brainstormed potential sanctions that western countries could threaten against Russia."Warnings of the pipeline's demise ramped up as Russia's invasion day approached. On January 27th, Victoria Nuland stated, "I want to be clear with you today: if Russia invades Ukraine, one way or another, Nord Stream 2 will not move forward". (This is the same Victoria Nuland who said "Fuck the EU" in the famous leaked phone call from 2014.) Then on February 7th, Biden stated, "If Russia invades ... there will be no longer Nord Stream 2. We will bring an end to it."

As I said, all the evidence (of which I'm aware) supporting the 'Nord Stream 2 theory' is circumstantial. So the theory is far from proven. But if true, it would suggest the U.S. has achieved an important tactical victory, as commentators like Niccolo Soldo have been arguing.

Since Russia's invasion, not only has Nord Stream 2 been suspended (and the company funding it gone bankrupt), but there has been a surge in U.S. natural gas exports to Europe. What's more, NATO is stronger than ever, and may soon welcome both Sweden and Finland - granting the U.S. unprecedented access to the Baltic Sea. Meanwhile, nations like Germany have promised to spend more money on defence, some of which will undoubtedly end up in the coffers of U.S. defence contractors.

Of course, the suspension of Nord Stream 2 and Russia's counter-sanctions aren't a 'win' for everyone: Europe may now face permanently higher energy prices. As the Belgian Prime Minister recently stated, "The next five to ten winters are going to be difficult".

Comment: Two objectives: 'Divide and conquer'. Score one USA.