But long before the canines arrived here, there were predatory doglike canid species who hunted the grasslands and forests of the Americas. A rare and nearly complete fossilized skeleton of one of these long-extinct species was recently discovered by paleontologists at the San Diego Natural History Museum.

This fossil belongs to a group of animals called Archeocyons, which means "ancient dog." It was embedded in two large chunks of sandstone and mudstone unearthed in 2019 from a construction project in the Otay Ranch area of San Diego County. The fossil dates to the late Oligocene epoch and is believed to be 24 million to 28 million years old.

While the fossilized remains are still awaiting further examination and identification by a canid researcher, its discovery has been a boon for the San Diego museum's scientists, including the curator of paleontology Tom Deméré, post-doctoral researcher Ashley Poust and curatorial assistant Amanda Linn.

Because the existing fossils in the museum's collection are incomplete and limited in number, the Archeocyons fossil will help the paleo team fill in the blanks on what they know about the ancient dog mammals that lived in the area we now know as San Diego tens of millions of years ago.

Did they walk on their toes like today's dogs? Did they burrow in the ground or live in trees? What food did they prey on and what animals preyed upon them? How did they relate to extinct doglike species that came before them? And, potentially, is this an entirely new undiscovered species? This new fossil is providing SDNHM scientists with a few more pieces of an incomplete evolutionary puzzle.

"It's like you've found a tree branch, but you need more branches to figure out what kind of tree it is," said Linn, who spent nearly 120 hours from December through February partially uncovering the fragile, and in some places, paper-thin skeleton from the rock. "As soon as you uncover the bones, they start to disintegrate ... I used a lot of patience, and a lot of glue."

Archeocyons fossils have been found in the Pacific Northwest and Great Plains states, but almost never in Southern California, where glaciers and plate tectonics have scattered, destroyed and buried deep underground many fossils from that period of history. The chief reason this Archeocyons fossil was found and made its way to the museum is a California law that requires paleontologists be onsite at major construction projects to spot and protect potential fossils for later study.

Pat Sena, the San Diego Natural History Museum's paleo monitor, was observing the rocks tailings in the Otay project nearly three years ago when he saw what looked like tiny white fragments of bone protruding from some excavated rock. He marked the rocks with a black Sharpie marker and had them moved to the museum, where scientific work soon ground to a halt for nearly two years because of the pandemic.

On Dec. 2, Linn started work on the two large rocks, using small carving and cutting tools and brushes to gradually pare away the layers of stone.

"Every time I uncovered a new bone, the picture got clearer," Linn said. "I'd say, 'Oh look, here's where this part matches up with this bone, here's where the spine extends to the legs, here's where the rest of the ribs are.' "

Poust said that once the fossil's cheekbone and teeth emerged from the rock, it became clear that it was an ancient canid species. In March, Poust was one of three international paleontologists who announced their discovery of a new saber-toothed catlike predator, Diegoaelurus, from the Eocene epoch. But where ancient cats had only flesh-tearing teeth, omnivorous canids had both cutting teeth in front to kill and eat small mammals and flatter molar-like teeth in the back of their mouths used to crush plants, seeds and berries. This mix of teeth and the shape of its skull helped Deméré identify the fossil as an Archeocyons.

The new fossil is fully intact except for a portion of its long tail. Some of its bones have been jumbled about, possibly as the result of earth movements after the animal died, but its skull, teeth, spine, legs, ankles and toes are complete, providing a wealth of information on the Archeocyons' evolutionary changes.

Poust said the length of the fossil's ankle bones where they would have connected to the Achilles tendons suggests the Archeocyons had adapted to chase its prey long distances across open grasslands. It's also believed that its strong, muscular tail may have been used for balance while running and making sharp turns. There are also indications from its feet that it possibly could have lived or climbed in trees.

Physically, the Archeocyons was the size of today's gray fox, with long legs and a small head. It walked on its toes and had nonretractable claws. Its more foxlike body shape was quite different from an extinct species know as Hesperocyons, which were smaller, longer, had shorter legs and resembled modern-day weasels.

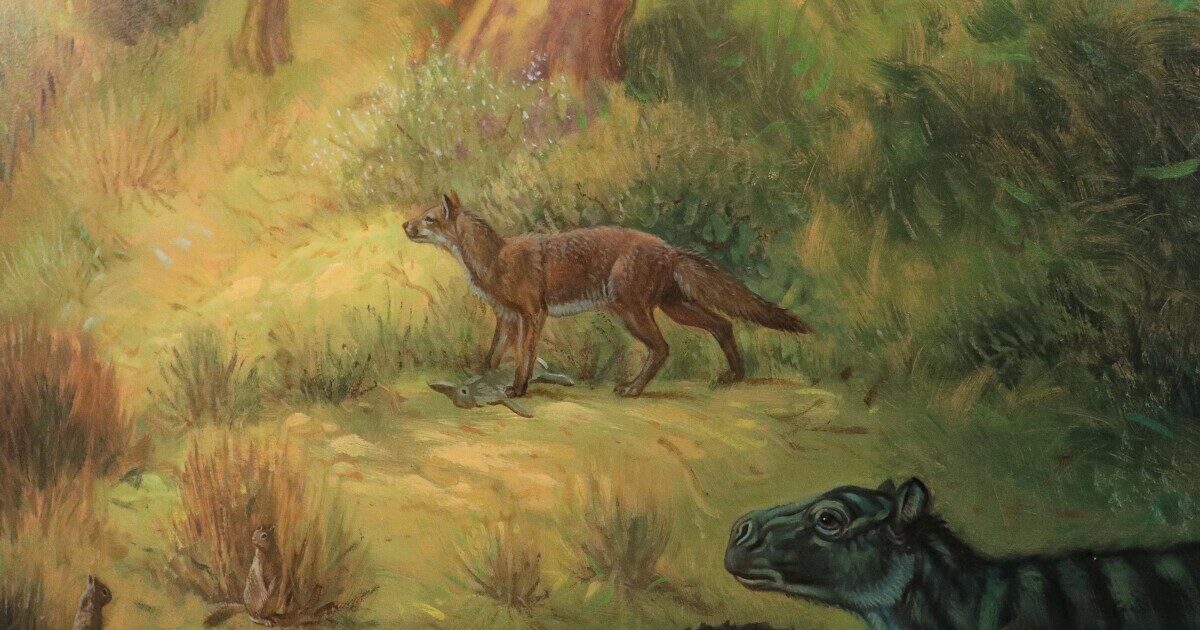

While the Archeocyons fossil is still being studied and not on public display, the museum does have a large exhibit on its first floor that features fossils and a large mural of animals that lived here in San Diego's coastal region during ancient times. Poust said one the animals in the mural painted by artist William Stout, a foxlike creature standing over a freshly killed rabbit, is close to what the Archeocyons may have looked like.

Once the Archeocyons fossil was partially identified in February, Deméré had Linn stop work on the fossil, leaving it partially embedded in the rock. He didn't want to risk any damage to the intact skull until it can be further studied by a world-renowned carnivore researcher like Xiaoming Wang of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

"Nothing makes a curator happier than having visiting researchers to the collection," Deméré said. "Hopefully, someone comes along. A nearly complete skeleton like this can answer all sorts of questions, depending on who's interested."

Comment: See also: 28,500 year old fossil site supports date for dog domestication during Ice Age