Patients with long Covid complain of numerous symptoms, the main ones being recurring fatigue and brain fog, muscle weakness, being out of breath and having low oxygen levels, sleep difficulties and anxiety or depression. Some patients are so sick that they cannot work or even walk a few steps. There is possibly also an elevated risk of stroke and heart attacks. One of the biggest sources of concern is that even mild and sometimes asymptomatic initial Covid-19 infection may lead to debilitating, long-term disability.

Since early 2020, we and other researchers have pointed out that acute Covid-19 is not only a lung disease, but actually significantly affects the vascular (blood flow) and coagulation (blood clotting) systems.

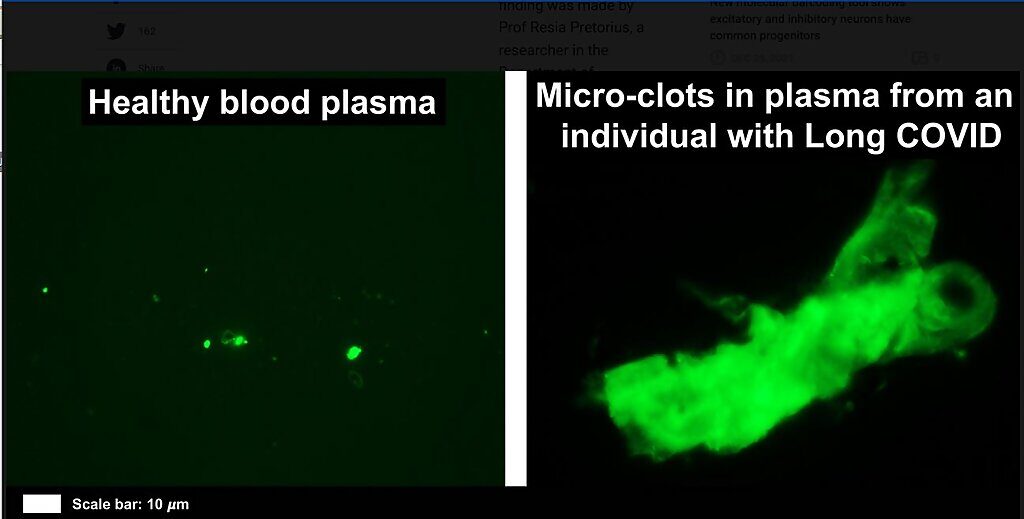

A recent study in my lab revealed that there is significant microclot formation in the blood of both acute Covid-19 and long Covid patients. With healthy physiology, clots may form (for instance, when you cut yourself). However, the body breaks down the clots efficiently by a process called fibrinolysis.

In blood from patients with long Covid, persistent microclots are resistant to the body's own fibrinolytic processes. We found high levels of various inflammatory molecules trapped in the persistent microclots, including clotting proteins like plasminogen, fibrinogen and Von Willebrand factor (VWF), and also Alpha-2 antiplasmin (a molecule that prevents the breakdown of microclots).

The presence of persistent microclots and hyperactivated platelets (also involved in clotting) perpetuates coagulation and vascular pathology, resulting in cells not getting enough oxygen in the tissues to sustain bodily functions (known as cellular hypoxia). Widespread hypoxia may be central to the numerous reported debilitating symptoms.

So why can long Covid patients not go to their nearest clinic or health care practitioner to find treatment options? Currently there are no general pathology tests readily available to diagnose these patients.

Desperately ill patients are told that their pathology test results are within normal/healthy ranges. Many are then told that their symptoms are possibly psychological and they should try meditation or exercise. The main reason the traditional lab tests do not pick up any of the inflammatory molecules is that they are trapped inside the fibrinolytic-resistant microclots (visible under a fluorescence or bright-field microscope, as our research has shown). When the molecular content of the soluble part of the plasma is measured, the inflammatory molecules, including auto-antibodies, are simply missed.

Preliminary results indicate that treatments such as antiplatelet and anticoagulation regimens have shown promising results in long Covid cases, provided there is careful professional monitoring of any danger of bleeding that might be caused by taking these medications. In addition to that, so-called Help (heparin-induced, extracorporal, lipoprotein/fibrinogen, precipitation) apheresis - in which microclots and inflammatory molecules are filtered out in a dialysis-style treatment - may also have positive outcomes for patients. (See a recent BBC interview with Dr Beate Jaeger and Dr Asad Khan.)

We urgently need to invest in more research and clinical trials to better understand and further confirm the link between abnormal blood clotting, hypoxia and vascular dysfunction in patients with long Covid. Even those without long Covid could benefit from such research, as symptoms noted in long Covid patients show many similarities to those seen in chronic and viral-related illnesses including myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) - another disease that has been dismissed as "psychological" for decades. Just because we have not yet identified a biomarker for long Covid does not mean biomarkers do not exist. We just need to look harder.

Resia Pretorius is the head of department and a distinguished research professor in the physiological sciences department, faculty of science, Stellenbosch University, South Africa

Comment: From MedicalXpress in October 2021