According to the study published in the journal Frontiers in Psychology on April 8, 2021, researchers found that persons with the highest number of errors demonstrated the highest degree of miscalibration, or overconfidence, in their actual performance on the cognitive reflection test.

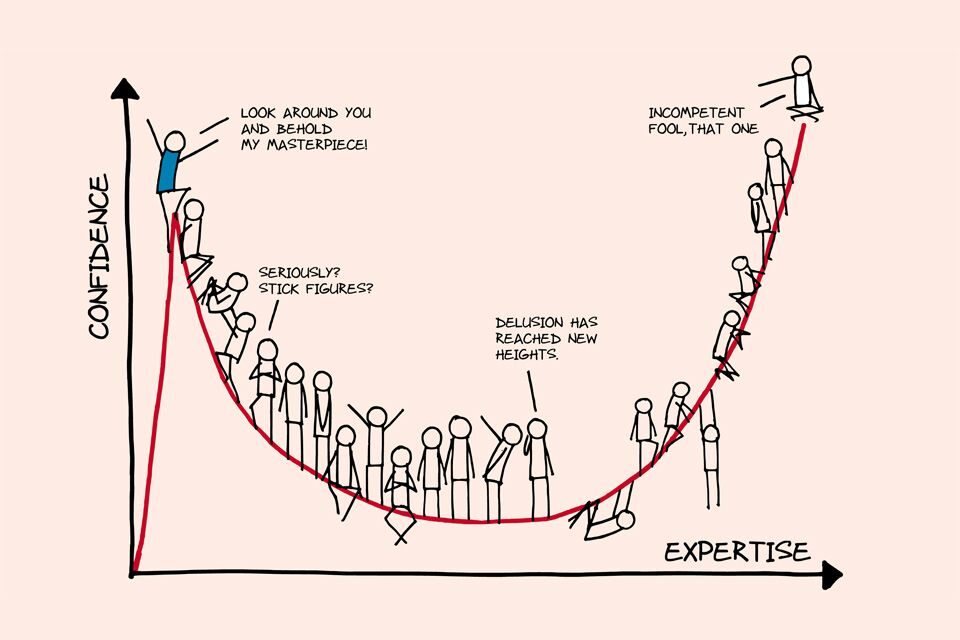

Researchers say study results have potential implications for the theoretical cognitive bias that persons with low abilities tend to overestimate their actual capabilities, also known as the Dunning-Kruger effect.

Speaking with The Debrief, Dr. Justin Couchman, professor of psychology at Albright College and co-author of the recent study, says the ability to make correct intuitive decisions is increasingly becoming one of the most critical skills to have in the modern information-technology age.

"In our current world, this is arguably the most important skill that exists," said Dr. Couchman. "We are swimming in a sea of misleading headlines, fake news, filtered pictures on social media, distorted context, and commentators who project a false sense of authority and trust. Almost all of which has the explicit goal of tricking our intuition. It is very hard to not feel the intuitive or natural reaction to anything you see in media, but if you can recognize the process and spot the trick, you are much more likely to avoid being swept up in something false."

Most everyone can recall a time when they've encountered someone unabashedly declaring they are correct and everyone else's contradictory opinion is uninformed and simply wrong. At times it may seem evident that this person doesn't know what they are talking about, however, they appear to be blissfully unaware of their ignorance.

In psychology, this phenomenon is known as the Dunning-Kruger effect, aptly named after the two research social psychologists, Dr. David Dunning and Dr. Justin Kruger, who first described it in their paper published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology in 1999.

In their paper, Dunning and Kruger suggested that persons who are unskilled or lack metacognitive competence suffer from a dual burden, which causes them to be unaware that they hold erroneous overly favorable views of their abilities. "Not only do these people reach erroneous conclusions and make unfortunate choices, but their incompetence robs them of the metacognitive ability to realize it," noted researchers.

To put it bluntly, the Dunning-Kruger effect says that due to cognitive bias, incompetent people are too inept to realize they are incompetent, which causes them to defend incorrect opinions or beliefs.

It's important to note the Dunning-Kruger effect has often been misinterpreted or misrepresented in non-academic settings, such as in the media.

Results of Dunning and Kruger's research did not show that incompetent people think they're better than competent people. Rather, it showed that bias causes incompetent people to believe they are more capable than they actually are.

In a blog post, University of Texas research professor of psychology Tal Yarkoni cautions that misinterpretations of the Dunning-Kruger effect can cause another cognitive bias - confirmation bias.

"Next time you're inclined to chalk your obnoxious co-worker's delusions of grandeur down to the Dunning-Kruger effect, consider the possibility that your co-worker's simply a jerk-no meta-cognitive incompetence necessary," Yarkoni writes.

Analysis Of Recent Study

In this recent study, researchers from Zayed University in Abu Dhabi and Albright College in Reading, Pennsylvania, examined how the Dunning-Kruger effect, or people's overestimation of their skills, can influence intuitive thinking.

The term "intuition" is not universally defined, with different disciplines using the word in varying ways. Generally, in psychology, intuition relates to using heuristic cues or pattern recognition to make decisions or possess knowledge without analytical thinking or apparent deliberation.

A wealth of research has demonstrated that intuition is a powerful and scientifically backed skill that can help people make faster and more accurate decisions. This innate ability for unconscious wisdom stems from the fact that the human mind is wired for pattern recognition.

To test the Dunning-Kruger effect on intuitive thinking, researchers used the "cognitive reflection test" (CRT) developed by Yale professor Dr. Shane Frederick.

The CRT is used to measure a person's ability to override an incorrect intuitive response and engage in analytical thinking to find a correct answer. Success on the test depends on a person's ability and willingness to overcome their initial intuitive response.

A frequently cited problem on the CRT is the question: "A bat and ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat cost $1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?" The intuitive answer that readily comes to mind is .10, which is incorrect. The correct answer is $.05 ($.05 ball + $1.05 bat = $1.10 total). To arrive at the correct answer, one must reject their initial "gut" response and engage in deliberative, analytical reasoning.

In the study, 178 female undergraduate students from Zayed University, Abu Dhabi, were asked to evaluate their performance after completing a seven-question cognitive reflection test. Participants were also asked to complete a self-reporting "faith in intuition" survey to measure their reliance on intuitive decision-making.

After analyzing the results, researchers found that participants with the most errors on the CRT miscalibrated their actual performance to a much higher degree than those who had fewer incorrect responses. "Specifically, on a test that was out of seven points, low performers overestimated their CRT score by 4.26, which high-performers miscalibrated by just 1," noted researchers.

Researchers said the results suggest that low-performers were either less likely to initiate analytical thinking to verify their intuitive responses, or the output generated by analytical processes failed to provide convincing evidence for them to overturn their intuitive reaction. The results could mean that low-performers and high-performers may not use the same heuristic cues when judging their intuitive decisions' accuracy. Low-performers may more heavily rely on less reliable suffice clues, such as answer fluency.

Researchers also found that participants who perceived themselves as more intuitive were the ones who had the most significant discrepancy in estimated vs. actual scores on the CRT. These results suggest that people who enjoy and trust intuition are less likely to recognize when they make a mistake, making them prone to overestimate their performance.

"This is a double burden that is unfortunately very common," explained Dr. Couchman. "People who consider themselves to be more intuitive probably notice and remember the times when their intuition worked, and forget when it was incorrect. That results in a deficit in knowledge, but also boosts their confidence in the incorrect process. Both of those problems work together to make it more likely they will make errors in the future."

Outcome: Can We Overcome The Dunning-Kruger Effect?

The study's results support the hypothesis that the Dunning-Kruger effect causes people to overestimate their ability to make sound, intuitive decisions. Because the Dunning-Kruger effect is an implicit or unconscious bias, preventing or mitigating errors caused by miscalibration of personal knowledge can be difficult.

"This is a very difficult question," explained Dr. Couchman. "We study metacognition, a form of self-awareness that helps you monitor your thoughts and regulate your behavior. But is there ever an instance when you truly override your strongest impulse?"

Dr. Couchman and his co-authors say that education "at all developmental levels" and awareness of the Dunning-Kruger effect, problems with intuition, and related cognitive biases could be key to reducing intuitive errors. "Interventions to improve self-awareness that specifically focusing on intuitive bias and fluency may help low-performers spot errors, improve metacognitively, and increase performance," said researchers.

"We know from both human and monkey studies that our minds are capable of learning to notice when we are facing uncertainty and adaptively respond to it," said Dr. Couchman. "Education is key. There is some hope that through education about intuitive errors and other cognitive fallacies, we could become better at mitigating our implicit biases. Metacognition often helps the implicit processes become more explicit, which is the best way of addressing bias. Rather than overriding your strongest intuitive response or fighting against it, you can learn to have other, more adaptive responses in the face of uncertainty."

The study: Dunning-Kruger Effect: Intuitive Errors Predict Overconfidence on the Cognitive Reflection Test was authored by Marina V.C. Coutinho, Justin Homas, Alia S.M. Alsuwaidi, and Justin J. Couchman, and published April 8, 2021 in the journal Frontiers in Psychology.

About The Author

Tim McMillan is a retired police lieutenant, investigative reporter and co-founder and Executive Director of The Debrief. His writing covers defense, science, and the intelligence community. You can follow him at lttimmcmillan.com and on Twitter @lttimmcmillan.

Reader Comments

he, he, he

Hmm...?

I didn’t bother to read the “research” links because it is almost certain they make similar mistakes.

I think what they really mean is that there is a curtain, behind which they cannot or dare not look; the actual deeper levels of the thinking process. The distinction they note among groups of people and their different levels of so-called ‘intuitive’ skills is easily explained by seeing those differences as greater or lesser abilities to look consciously deep inside their minds while processing information . The authors simply imply that it is impossible to penetrate that curtain (because they certainly have not!).

In any case, they are sure they are ‘on to something’ even if they can’t clearly explain what it is. Now that’s what I call biased thinking which results in overconfidence. D-K BINGO!

Hmm...?

And then there's that whole cognitive dissonance thing you have to deal with.

In my experience, the intuitive voice is at its best or "truest" when we are in a positive state of mind, without being influenced by negative emotions. Pride or ego, fear, jealousy or anger.

This is a very difficult state to achieve, for anyone and needs alot of work, so the over confident voice may be influenced by false pride and ego? Spiritual work like "adaptive responses" could be akin to being aware of which kind of emotions are linked the to the ideas and concepts in our minds, and which outcomes they produce in acual life? Negative or positive ones.

It's probably worth including about how emotions and the level of emotional intelligence can influence the intuitive voice.

Yes we definitely need all the help we can get, and if all else fails I can rely on bitter experience to come and give me a well deserved kick up the backside 😅