Gagarin's rocket, Vostok 1, carried him into orbit, after which he circled the Earth for 108 minutes before returning to the ground. With this, Gagarin became the first human to successfully travel into space.

The Soviet space program had strange origins. In the dying years of the old Russian empire, an eccentric librarian in Moscow dreamt up the idea that humanity's "common task" was to resurrect the dead. Humanity would have to scour the universe to find the dust into which our ancestors had dissolved, and then colonize other planets to provide room for their newly revived bodies.

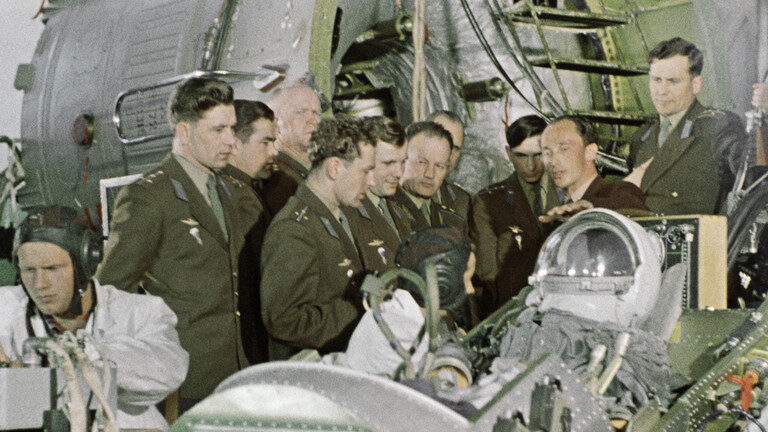

Few people read the work of Nikolai Fyodorov, but one who fell under his spell was a student named Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, who studied at the library where Fyodorov worked. Tsiolkovsky went on to become the pioneer of modern space travel, being the first person to develop the theoretical mechanics of rocketry and spacecraft. His work influenced future space engineers, including the German rocket scientist Wernher von Braun and Soviet space program chief Sergei Korolev.

In the eyes of Fyodorov and Tsiolkovsky, space travel was a tool for the common cause of humanity. After 1945, however, the Cold War turned it into a facet of the global struggle between the Soviet Union and the United States. Both countries sought to achieve technological 'firsts' that would demonstrate the superiority of their respective economic systems - communism and capitalism. Gagarin's flight was a phenomenal propaganda victory for the Soviet Union.

In the early 1960s, communism's economic failings were not yet clear to everybody. Under the leadership of Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet Union enjoyed an economic boom, encouraging the belief that it could eventually catch up and even pass the United States. Images abounded of 'red plenty' resulting from the application of scientific knowledge and rational economic planning. Meanwhile, Western states were in constant retreat; great colonial powers rapidly abandoned their empires, and Western countries suffered a series of humiliating defeats, such as those of both France and the United States in Vietnam.

Gagarin's flight symbolized America's vulnerability in the face of a future that seemed to belong to communism. It induced something like a sense of panic in the United States. As Newsweek wrote: "Time and space are running out for the United States. The first man into orbit was a Russian. And next? A rocket to Mars? The Russians won't pass up the chance when the firing conditions are right. The first man on the moon? Most likely, he'll carry the hammer and sickle."

Newsweek got it wrong. Gagarin spurred the US into action, with the result that in 1969, an American, Neil Armstrong, became the first man to step on the moon. Nevertheless, Gagarin represents a moment in time when the bubble of American superiority was temporarily burst. It also remains a symbol of national pride for citizens of Russia.

Gagarin's achievement did not come out of nowhere. The Soviet Union invested huge sums of money into science, going so far as to create specialized scientific towns where the intellectual elites of the country could devote themselves to pure and applied research. Science, it was believed, was the key to the future.

Unfortunately for the Soviets, "the invisible hand of the market" proved to be a stronger force, and when the Soviet Union collapsed, funding for science in Russia dried up. A 2010 report by Thomson Reuters noted "the total neglect of fundamental science by the post-Soviet governments in Russia, especially from 1992 to 2002." Since then, the situation has improved somewhat, but the neglect of the 1990s has left its mark. In 2018, Russians published 81,579 scientific and technical journal articles in fields such as physics, biology, chemistry, and mathematics. This compares with 528,263 published in China, and 422,808 in the United States. Clearly, Russia is well behind.

That said, it is far from being a scientific minnow. Its 81,579 articles put it in seventh place in the world, after China, America, India, Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom. When the dust settled after the collapse of the Soviet Union, something remained of the old scientific infrastructure. Russia retains some world-class areas of specialization. These include nuclear physics, aviation, and military technology. Russia's success in rapidly producing three vaccines for the Covid-19 virus is a sign that the country retains considerable scientific-technological potential.

Another field of expertise is space. A week ago, the Russian government approved an extension until December 2030 of its agreement with the United States on space cooperation, and on Friday a joint Russian-American crew launched successfully from Baikonur and joined the International Space Station. Meanwhile, in March, Russia and China agreed to work together to build a joint lunar base.

The Russian space agency Roscosmos declared that the lunar outpost would provide an opportunity for "the use of outer space for peaceful purposes in the interests of all mankind." Once an area of competition, it would appear that space is now a sphere of international cooperation. In this sense, it is perhaps at last meeting the dream of humanity pursuing a "common task," rather than being a source of rivalry, as it was 60 years ago when Yuri Gagarin undertook his heroic journey into orbit and opened a new era in human history.

Paul Robinson, a professor at the University of Ottawa. He writes about Russian and Soviet history, military history, and military ethics, and is author of the Irrussianality blog

Tsiolkovksy put it on paper, and surely deserves the credit for being the inspiration for those rocketeers who made it a practical reality. But he never proved his ideas by making and launching a rocket. Michelangelo was also a visionary, made lots of designs on paper, but he actually got many of them built and operational. That is the whole point of science.

And I would keep a tongue in cheek calling what has been done outside of Earth's gravitational well as "travel." In terms of the vastness of "Space", the distances involved just within the Solar system, its like riding down to the corner Mom & Pop's food store on a bike. Hardly what one can classify as travel. As I recall in my youth reading about the "Space Program" post WWII, there had been a lot of people around the world working on these ideas of how to get out of the atmosphere. a fair amount of overlap and synchronicity, so being "first" at it doesn't carry all that much prestige.