There was a recent article in The Washington Post entitled "Meat is Horrible", once again vilifying meat, that was full of inaccurate statements about the harm cattle impose on the land, how bad it is for our health, and how it should be taxed. Stories like this are all too common and we've absolutely got to change our thinking on what's causing greenhouse gas emissions and our global health crisis.

Hint: it's not grass-fed steak

In the few days since the story originally came out, I've been brewing up some different angle to write. I've written here, and here about the benefits of red meat, and how Tofurky isn't the answer to healing the environment or our health. I keep saying the same thing over and over. Recently, I posted this as a response to Arnold Schwarzenegger's new claims that a plant-based diet is optimal. I also wrote about Philadelphia's sugar tax here, and I don't think a meat tax is any better of an idea, especially when the government is subsidizing the feed. I'm feeling quite frustrated.

This morning, I went back to see the post and noticed that the story has been "significantly revised to address several inaccurate and incomplete statements about meat production's contribution to greenhouse gas emissions." Most of the original points, references and charts are missing. However there are still some important pieces of information that I feel the author missed. The main one being that meat itself isn't evil, it's the method by which we farm it (feed lots and CAFOs-Confined Animal Feeding Operations) and how we prepare it (breaded and deep fried), and what we eat alongside it (fries, and a large soda).

Meat isn't evil, it's how we raise it, how it's prepared, and what it's eaten with.

Stop hating the player and instead, hate the game. Humans have been eating meat for all of our existence. Why vilify it now? I think what most people are really upset with are modern agricultural techniques and hyper-palatable, ultra-processed foods. Those are the real issue here, not a grass-fed steak. I'll address some of the points directly:

Water, Carbon and Methane

Here's a direct quote from the Meat is Horrible post:

"For a kilogram of meat, you need considerably more water than for plant products."

What most people don't understand is that there are different ways of measuring water use. If you're measuring meat production looking at "green water", this is very different than looking at "blue water." Below are definitions from Waterfootprint.org's glossary:

Green water

"The precipitation on land that does not run off or recharge the groundwater but is stored in the soil or temporarily stays on top of the soil or vegetation. Eventually, this part of precipitation evaporates or transpires through plants. Green water can be made productive for crop growth (although not all green water can be taken up by crops, because there will always be evaporation from the soil and because not all periods of the year or areas are suitable for crop growth)."

Blue water

"Fresh surface and groundwater, in other words, the water in freshwater lakes, rivers and aquifers."

Grey water footprint

"The grey water footprint of a product is an indicator of freshwater pollution that can be associated with the production of a product over its full supply chain. It is defined as the volume of freshwater that is required to assimilate the load of pollutants based on natural background concentrations and existing ambient water quality standards. It is calculated as the volume of water that is required to dilute pollutants to such an extent that the quality of the water remains above agreed water quality standards."

I want to also explain something that a lot of people don't know. All beef is actually "grass-fed", meaning the cattle start their lives on pasture (usually 12 to 14 months) and are "finished" (for four to six months) on a feed lot. In "typical" cattle production, the green water number is about 92%. In grass-finished beef, the green water number is closer to 97-98%. Again, green water is primarily rain fall. So every drop of rain that falls to grow crops, forage or grasses that a head of cattle eats over its lifetime is part of the water footprint equation. Blue water is ground water (from aquifers and rivers used for irrigation). See the full report from waterfootprint.org here. The research paper referenced in the Washington Post article considers industrially raised beef preferable to pasture-based because less water is needed to raise grains than to grow grass (looking at rain - green water). No note on how much of the pasture land herbivores are grazing is completely unsuitable for crop production is made, nor how beneficial these animals can be to the restoration of the land.

According to this study from UC Davis, which used the blue water methodology, "typical" beef requires approximately 410 gallons of water per pound to produce. A pound of rice production also requires about 410 gallons, and avocados, walnuts and sugar are similarly high in water requirements. In Nicolette Hahn Niman's book, Defending Beef, she explains that the amount of water for grass-fed beef is closer to 100 gallons per pound to produce.

Once you understand how these footprint numbers are derived, you'll understand how meaningless it is to use them as a critique of meat production. The equations also leave out a lot of critical information like soil type and health. This video by Sandra Postel, the director and founder Global Water Policy Project, explains water use in the production of meat very well. It should also be noted that the nutrition in grass-finished beef is far superior to rice, avocados, walnuts and sugar, so comparing "plant products" to "meat" is not really logical.

Soil Health

Cows urinate and poop, which adds water and microorganisms to the soil, increasing biodiversity underground and helping to sequester carbon. Cattle grazing stimulates grass growth, which is good for the health of the pasture. They walk on the ground, which allows for rain water to pocket and seed germination to take hold. None of this happens in a chemical, monoculture system of farming. In the absence of herbivore manure,

scientists are actually now experimenting with inoculating soil with microbes. In my book, I refer to soil as a bank account. Cropping the soil (like planting vegetables) withdraws nutrients, and with each harvest, and you need to replenish the account. Conventional agriculture does this poorly with chemical fertilizers, producing GHG (Green House Gas) emissions, which are largely overlooked when people are singing the praises of eating vegetables. Home gardeners and organic farmers know that the best way to improve the soil bank is to add compost, ground bone, blood, and animal manure. Properly managed herbivores are also adding to the soil bank in a natural way.

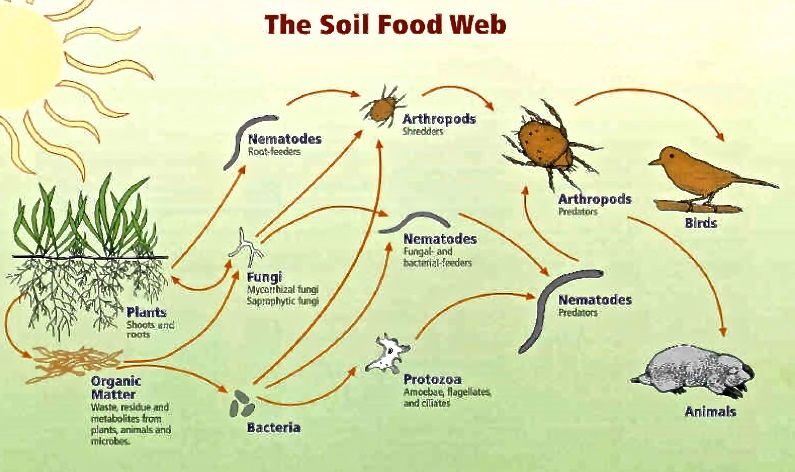

Soil is not simply "dirt," but is instead a complex web:

Click here for a really great explanation of how healthy pastures, under good grazing techniques, can sequester carbon.

According to this paper, from the March/April 2016 issue of the Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, most agricultural soils have lost 30% - 70% of their soil organic carbon (SOC), which has led to a decrease in food production in some areas. Domestic ruminants represent 11.6% of total anthropogenic emissions, vs. soil-associated losses, which contribute 13.7%. Of that 13.7%, nearly half results from agricultural inputs like fertilizers, fuels and pesticides. Wind, water and tillage erosion constitute the remaining emissions. Poor agricultural practices have contributed to soil erosion three times greater than the combined yields from corn, soybeans and hay.

Continuous grazing, where the land is not allowed to rest, depletes the root biomass, increases the bare ground, lowers SOC reserves, and contributes to soil erosion and compaction, decreasing it's water holding capacity. Sediments from eroded soils, both due to overgrazing and poor cropping, emit GHG when organic matter sediments enter anaerobic waterways. Areas like the dead anoxic zone of the Gulf of Mexico, as well the declining numbers of North American pollinators, are examples of what can happen from soil erosion. (See the full paper here)

In the above video, Dr. Jason Rowntree of Michigan State (at about 37:00) reports that regenerative grazing of cattle can produce a 30 - 40% improvement in soil carbon compared to where there was no grazing at all. He also cites that more intensive grazing proved better for soil health than less intensive.

The talk below by Precious Phiri of Zimbabwe illustrates how extremely brittle land (much of the earth's surface) can heal with properly managed grazing livestock. It would be crazy to plant row crops in such a brittle environment. Herbivores however, can restore the land to fertile soil.

Another quote from the Meat is Horrible post:

"The methane produced by cattle digestion alone is what leads many researchers to call for focusing on the impact of red meat, rather than poultry or pigs. Pigs and poultry contribute only 10 percent of total livestock emissions."

Let's not forget that prior to the mid-1800's, there were an estimated 30-60 million bison roaming North America, yet nobody seems to acknowledge this when citing current "devastating" herbivore numbers. When the animals are incorporated into a responsibly managed, natural system, mimicking the way nature works, the entire system works.

Most of the CO2 emission numbers for food items comes from the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs [DEFRA]. While their analysis did take into account all sources of GHG during production, the numbers stop at emissions. No accounting for mitigation from carbon sequestration or methane oxidation, or nitrogen fixing were included. The worst emissions in this scenario (looking only at emissions) will be the animals who take the longest to reach mature weight, like grass-fed cattle. When you look at the entire cycle, cattle, responsibly rotated on pasture, have at minimum a net neutral and likely a net gain for carbon sequestration. Concentrated animal feces from factory farms (like manure lagoons) are a much different environmental issue than scattered cattle poop, urine and hoof across grasslands in a natural system.

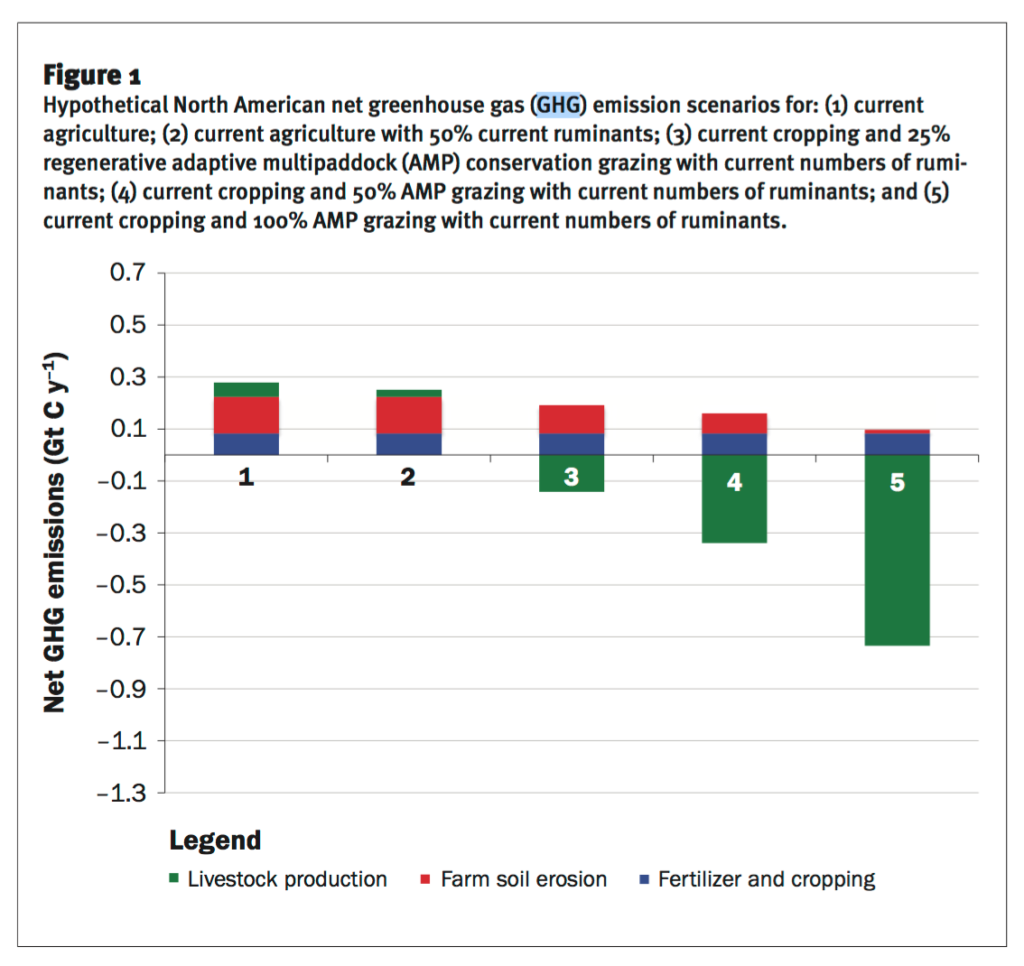

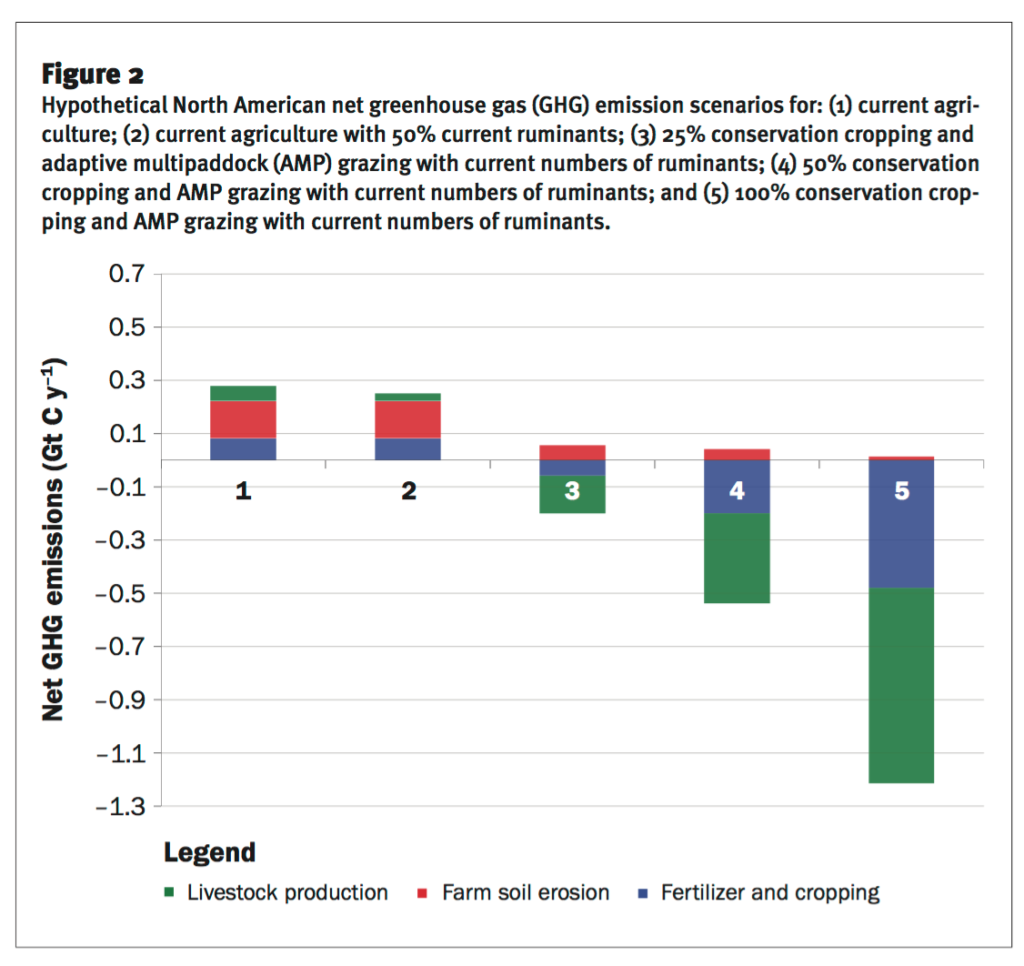

These graphs, from the same study as referenced earlier, show what can happen when we look at agriculture differently.

Let's take a look at land use:

A common question is: How are we going to feed the growing population? If we are going to eat less meat and have more crops, what will this look like?

Currently, 11% (1.5 billion ha) of the Earth's land surface is used for crop production (annual crops and "permanent" agriculture like tree fruit). The FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization) suggests that this is about 1/3 of the potential land mass (2.7 billion ha) suitable for crop production. That leaves a large amount of the land that is only suitable for grazing animals. In fact, most of the surface land on Earth is only suitable to grazing animals and not for crop production, due to topography, humidity, and other issues. What's also not taken into account are the other potential uses this cropland may have for humans (such as housing, industrial uses, etc), so the total amount of usable land for cropping is likely much less than that number. Also, about 45% of potentially arable land is currently in forest. Read the full FAO report here.

"The stupidity of man comes from having the answers. The wisdom comes from having the questions." Milan Kundera

How we're going to feed the world is much more complicated than asking people to simply eat more plants and less meat. How are we going to crop this land? Are we going to use more chemical agriculture? What are the expected yields? How will this land be irrigated? What will be planted and is there a demand for it? An example is the Democratic Republic of Congo where more than 50 percent of the land is suitable for cassava but only 3 percent is suitable for wheat. Is there a demand for cassava? What do they do with surplus cassava? Can it be stored? What processing or energy is needed in order to store it? What about North Africa, where olives can thrive but water intensive crops like rice cannot? Is this land actually fertile, free of toxins, and is there infrastructure for farming? Can the country store the excess crops? In highly populated countries like India, storage for surplus crops is a huge issue. If we want people to eat more fresh vegetables and fruit, how are we going to transport them without spoilage? Are we going to process them? Are we going to fly ripe apples from New Zealand to England in the winter, or are we going to store England's apples and eat them in the winter? Counter to what some assume, in the case of apples and England, it actually makes more sense to fly in seasonal apples from New Zealand than to store local apples for the winter. Here's another question: should we be eating out of season apples to begin with?

Now let's look at human nutrition:

"Research from the University of Oxford estimates billions of dollars could be saved if people cut down to expert-recommended dietary guidelines - meaning no more than 0.6 pounds of red meat per week, 50 grams of sugar per day and 2300 calories per day."

That statement above is saying that we can eat more sugar than red meat (78 grams more sugar per week than red meat). Really?

The truth is, much of these dietary guidelines are not only unproven for human health, but are highly debated in terms of sustainability. This article (and there are lots more like this) shows that the vilification for red meat is based on observational studies, showing links but not proving cause. It also points out that randomized control studies fail to prove that reducing red meat has a positive effect on health.

If we want to raise healthy cows, let's look at the diet they've evolved to thrive on. Similarly, if we want to be healthy humans, doesn't it make sense to eat the food we've evolved to eat?

In this post, I illustrate that our worldwide nutrient deficiencies are Iron and B12. Reducing meat consumption will not solve this. This post illustrates how nutrient-dense red meat is in general, and this one shows how much better beef finished on grass is, compared to typical beef. Eating more grains will not curb our global obesity or type 2 diabetes epidemic.

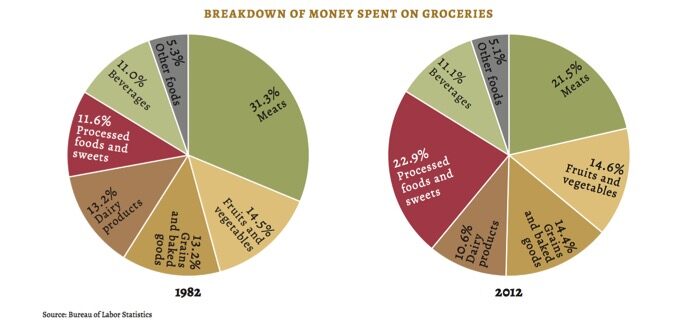

So, what are we eating more of?

Americans are spending less on meat today compared to years before, but twice as much on processed foods and sweets.

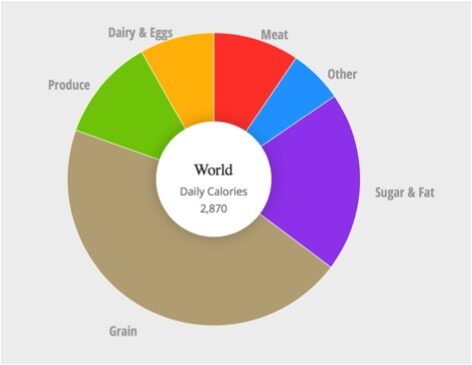

Globally, what are we eating?

The world is eating a lot of grain, sugar and fat. Here's a breakdown of this chart... and click here to interact with these graphs on your own - it's completely fascinating!

- Grain - 45%

- Sugar & Fat - 20%

- Produce - 11%

- 5% Starchy Roots

- 3% Vegetables

- 3% Fruit

- Dairy & Eggs - 8%

- Meat - 9%

- 1% Beef

- Other - 6% ( alcohol and pulses )

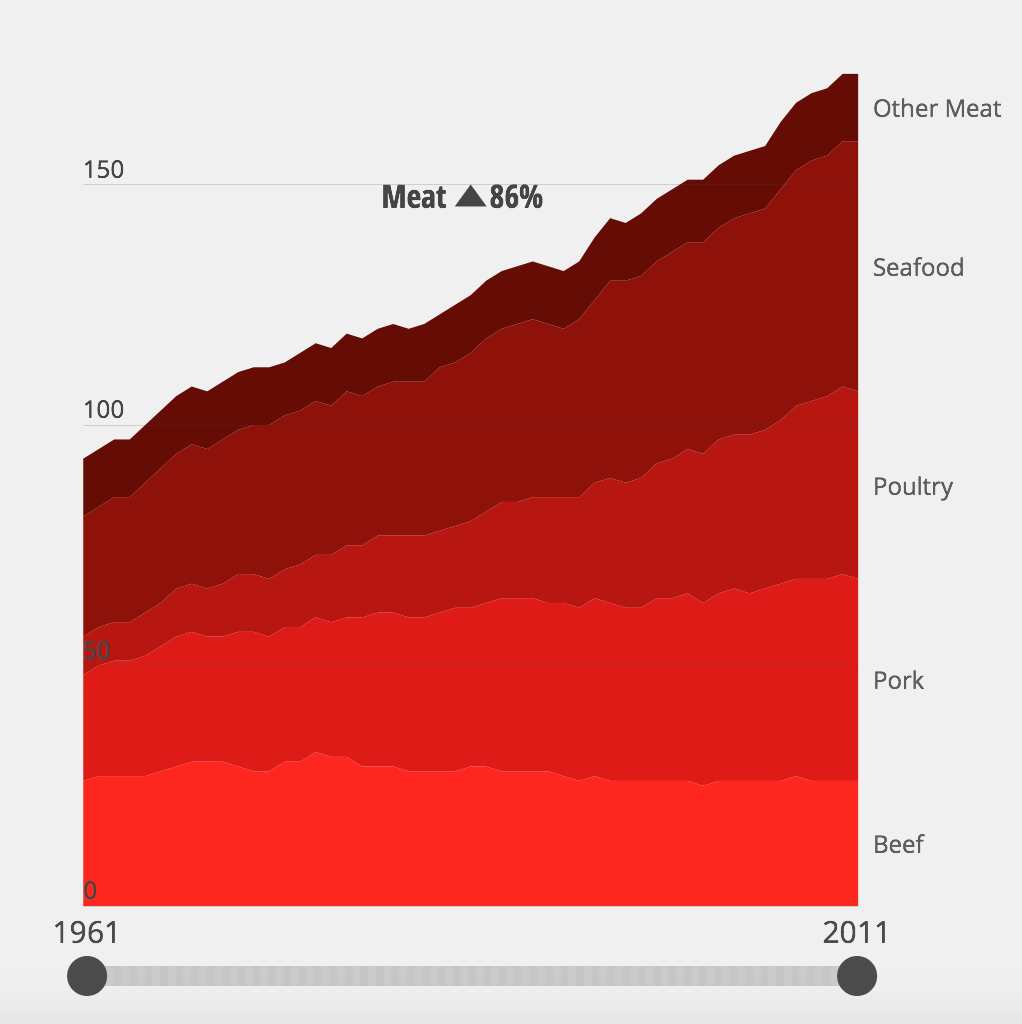

Beef consumption saw a 0% growth over this 50 year time period, while chicken consumption increased nearly 400%. Chickens and pigs are raised primarily indoors, fed heavily sprayed, mono cropped grain (plus some antibiotics, leading to superbugs, and can barely move around). Even feed-lot beef has a better life than a CAFO-raised chicken and pigs, and the cows are eating grass for most of their life. I'm just not sure beef is really the villain that everyone is claiming it to be.

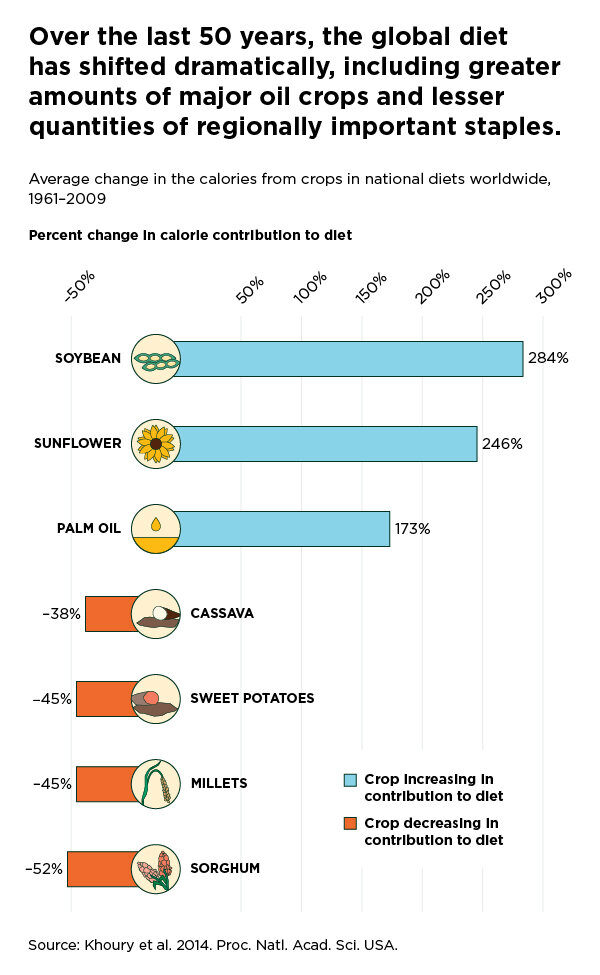

According to this recent NPR post, the global diet is getting more and more westernized.

Is it really safe to narrow down our crop production to a handful of crops, grown by a handful of companies? Nutritionally speaking, I'm not sure that the Standard American Diet is really the best diet for everyone on the planet. They were wrong about saturated fat and cholesterol. However, many other countries are following in our footsteps, adopting food pyramids, including more grains, and advising their people to reduce their meat consumption. I'm just not sure where those extra calories are going to come from. Is it realistic to think they will replace factory-farmed meat with organically grown vegetables and fruit? How will they get their protein? Is lab-grown meat really the best solution for a growing population? Has anyone done a Life Cycle Analysis on a product like Soylent, Tofurky, the "Beyond Meat" burger meat in the promotional video that the "Meat is Horrible" post prominently displays like an endorsement? Are these products are truly sustainable solutions? When you take into account the amount of chemicals and fossil fuels needed to grow and transport the soy and wheat, the amount of water needed for irrigation and processing, and the all of the other inputs needed to process, package and store these products, naturally produced, grass-finished beef seems like a much better choice to me. Beef is also a better source of protein than plants, and remember that our largest global nutrition deficiency is iron. The iron in beef is much more bioavailable than the iron in soy.

Solutions:

According to this paper (also cited earlier) here are a few suggestions to move into a more sustainable agriculture pattern:

- More diversified farms

- Cover crops with row crops

- Cover crops between rotations

- Minimize nongrazing feeding of ruminants

- Organic soil amendments instead of chemicals

- Using herbivores to improve marginal land to permanent pasture

- Rest the land

A sustainable diet includes pasture-based meat and avoids processed foods and sugar.

We need to stop imposing the western diet on developing countries, and start worrying about what our low-fat, highly processed dietary guidelines have done to our health. We need to cook more. We need more small-scale, sustainable farms feeding regions and less factory farms feeding masses. Red meat is not causing obesity and type 2 diabetes, and not all meat production is evil. When we have a more clear understanding of natural cycles and do our best to mimic them, we can find superior solutions for human health and for our environment. We need to eat a truly sustainable diet, which includes grass-finished red meat and other pasture-based meat, plus sustainable seafood, lots of fresh, locally grown organic vegetables, some seasonal fruits, and healthy fats.

Comment: Red meat consumption is actually excellent for optimal human health