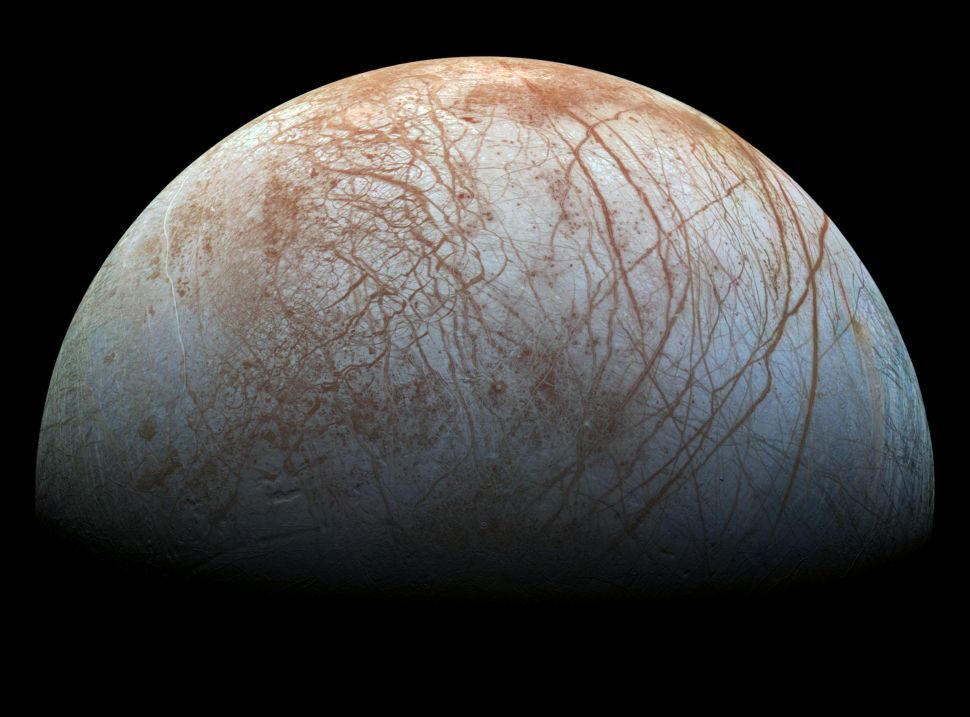

© NASA/JPL-Caltech/SETI Institute

Jupiter's icy moon Europa experienced enough heat to produce a layered interior and subsurface ocean, scientists say. The finding could help researchers learn about the potential for life on other worlds.

Mohit Melwani Daswani, a planetary scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, led a team that analyzed data gathered by the Galileo mission. Beginning in the mid-1990s, Galileo studied Jupiter and its moons for about eight years and discovered that a global ocean of liquid water likely exists under the icy surface of Europa.

Daswani's team found that a layer-creating phenomenon called differentiation may be the reason Europa has its ocean. Daswani announced his findings Wednesday (June 24) during a presentation at the virtual Goldschmidt conference, an annual conference on geochemistry and related fields. The work has yet to be peer reviewed.

Europa has some key features suspected to be necessary for a habitable world, Daswani told Space.com in an interview. Daswani's findings could have implications for the study of habitability on other worlds, even those beyond the realm of our sun. The team hopes that upcoming missions like NASA's Europa Clipper, due to launch later this decade, will help determine if the icy moon is indeed habitable.

Daswani's team found evidence of a promising sign: Europa's ocean could have originated from the breakdown of water-bearing minerals that were in the interior of Europa. That process may have occurred during differentiation, during which Europa was "separated into distinct layers, sort of like an onion," he said.

"The interior of Europa is much denser than the outer layers," Daswani said. "That already tells us a really important property of Europa's history and geology: It must have experienced high heat in order for that process of differentiation to occur." That past high heat also increases the odds that Europa currently has enough heat to hide a liquid ocean.The source of that heat could be radioactive decay in the moon's interior, or a phenomenon called tidal dissipation caused by interactions with Jupiter and large nearby moons, or some of both, Daswani said. With liquid oceans, Europa has one important characteristic to supporting life. This process of differentiation happened on the key habitable world, Earth, as well as on Mars. "Europa was large enough to experience that as well," Daswani said.

There isn't a direct connection between differentiation and habitability, but Daswani said that this process of breaking down minerals via heat to produce oceans is perhaps not unique to Europa. "Large ocean worlds that experience this heat in the interior may have a mechanism to build oceans," Daswani said. By looking at the processes that led minerals to release water on Europa, scientists could figure out if an exoplanet might host a liquid ocean, because this may be a common way for oceans to form on worlds in our solar system and beyond.There is a solar system world with an ocean that doesn't seem as promising for life, Daswani said. "The exception to this would be [Saturn's moon] Enceladus ... [it] is a much smaller body than Europa and couldn't have experienced such high heat, and we know this because Enceladus' density is much lower than Europa's density. The ocean must have been created by a different process."

But Europa's neighbor Ganymede could also have a differentiated interior and might be similar to Europa in that regard.

Of course, life needs more than just water to exist. "Life is chemical. Life powers itself with chemistry, which is all about the flow of electrons," Steve Mojzsis, a geologist at the University of Colorado who wasn't involved in the new research, told Space.com in an interview. The exchange of electrons yields energy, and it's this kind of energy that gets used for metabolism.

In the future, Daswani wants to research whether or not there is sufficient energy for life to exist in Europa's ocean.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter