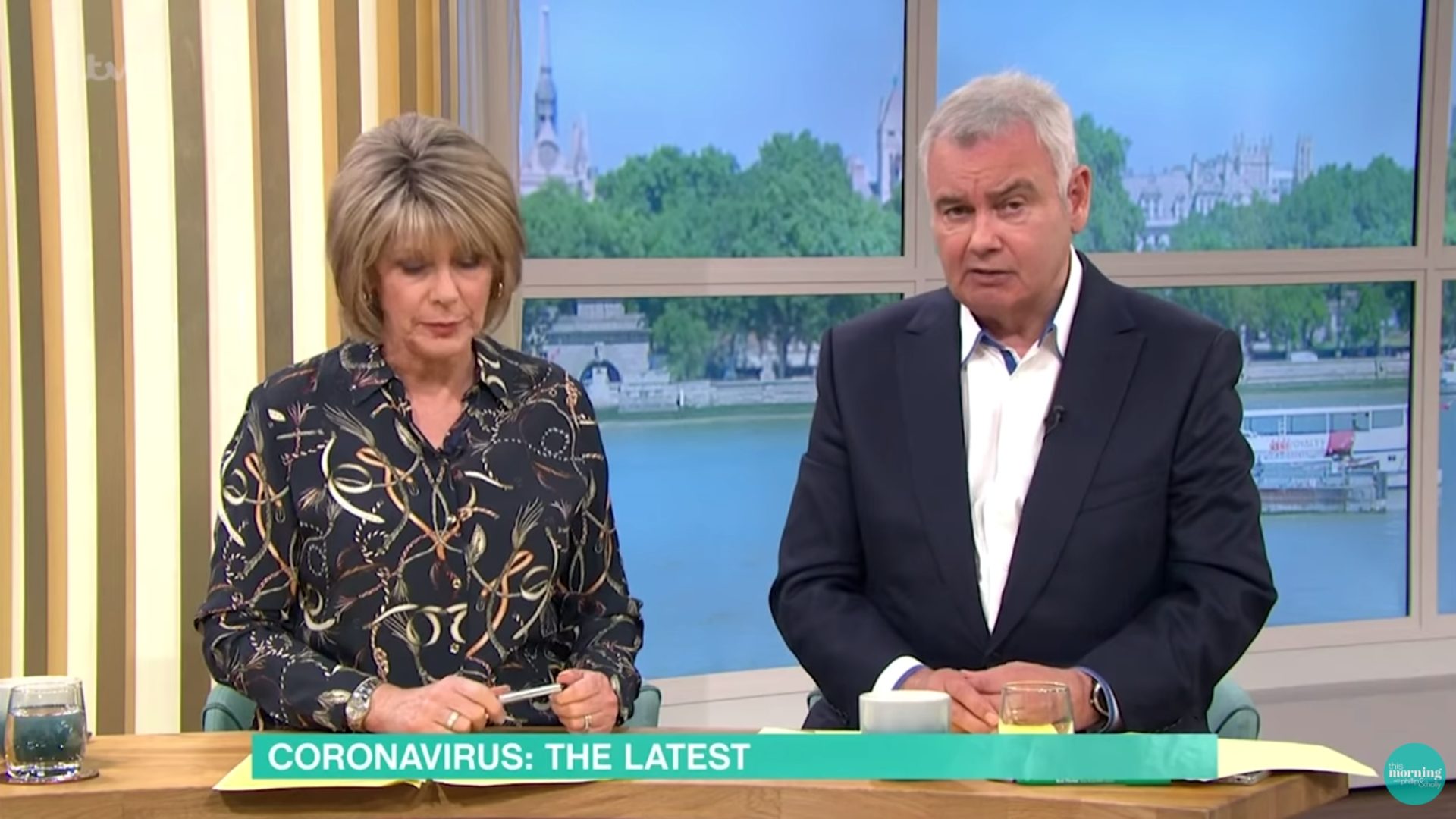

Eamonn Holmes on This Morning

In my capacity as the general secretary of the Free Speech Union, I

wrote to the chief executive of Ofcom, Dame Melanie Dawes, on 24 April to complain about its reprimand of Eamonn Holmes.

According to the regulator, the breakfast television presenter had said something that 'could have undermined people's trust in the views being expressed by the authorities on the Coronavirus and the advice of mainstream sources of public health information'. Holmes's sin, in Ofcom's eyes, was to say on ITV's This Morning that any theory running counter to the official government line - such as the one linking 5G masts and Covid-19 - deserved to be discussed in the mainstream media. This was in spite of Holmes saying the 5G conspiracy was 'not true and incredibly stupid'. Ofcom said this view - the view that such theories deserved a public hearing, not that they were in any way right or plausible - was 'ill-judged and risked undermining viewers' trust in advice from public authorities and scientific evidence'.In my letter to Dame Melanie, I pointed out that if Ofcom is going to prohibit views being discussed on television that might risk undermining viewers' trust in public authorities during this crisis, that could easily be extended to anyone challenging the government's official line on a number of issues, not just the link between the virus and 5G masts. For instance, would Ofcom have reprimanded a broadcaster that challenged the

advice of Public Health England, issued on 25 February, that it was 'very unlikely that anyone receiving care in a care home or the community will become infected'? That advice was supposedly based on 'scientific evidence', yet as we now know it turned out to be wrong and the fact that hospitals discharged elderly patients back into care homes without first confirming that they were not infected with Covid-19 is one of the reasons that, according to the ONS, as of 1 May,

37.4 per cent of all Covid deaths in England and Wales have occurred in care homes.

Given that bad advice and misinformation about the virus is being disseminated in the public square, both by authorities like Public Health England and conspiracy theorists like David Icke, the best way to minimise any harm to the public is not to prohibit public discussion of that advice and information, but to encourage it, so that members of the public (and care home managers) can make informed decisions about what advice to follow and what information to believe. To take the example of the theory Eamonn Holmes was referring to, if broadcasters aren't allowed to discuss whether there's a connection between 5G masts and the symptoms associated with Covid-19 - and present its exponents with the overwhelming evidence that there is no such connection - people are more likely to believe the theory, not less. They will think, 'If it's untrue, why is discussion of it forbidden by a state regulator?' As the US Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis said in his famous Whitney v. California opinion in 1927,

'If there be time to expose through discussion the falsehood and fallacies... the remedy to be applied is more speech, not enforced silence.' In other words, sunlight is the best disinfectant.In addition to Ofcom's rationale for reprimanding Eamonn Holmes being based on the mistaken belief that the most effective way to persuade people that conspiracy theories and fake news are untrue is to forbid their discussion, there's a further problem, which is the arbitrariness with which Ofcom applies that principle. If Ofcom is going to provide itself with a license to prohibit discussion of anything likely to risk 'undermining viewers' trust in advice from public authorities' then why did it not reprimand those broadcasters who publicised the fact that Professor Neil Ferguson, one of the key scientists advising the Prime Minister on how to respond to the pandemic, broke social distancing rules to spend time with his girlfriend? Surely, that was more likely to undermine 'people's trust in the views being expressed by the authorities on the Coronavirus and the advice of mainstream sources of public health information' than any discussion of the theory linking 5G masts to coronavirus?

Of course, no sensible body would seek to restrict the reporting of Professor Ferguson's breach of the lockdown rules, least of all the Free Speech Union. But that reporting engages precisely the same issue identified by Ofcom, namely, it had the potential to reduce the public's trust in the government's advice. So how does Ofcom distinguish between matters which, when broadcast, reduce trust but are nonetheless legitimate in its eyes, and those which are not? It does not say. Yet Ofcom hasn't reprimanded any broadcasters for publicising or discussing Ferguson's behaviour. Given how arbitrary Ofcom's application of its own rules is, how can broadcasters reasonably be expected to comply with them? What Lord Sumption said about the law in a

Supreme Court judgment issued last year applies to Ofcom's rule prohibiting discussion of views that could undermine viewers' trust in public authorities:

'The measure must not therefore confer a discretion so broad that its scope is in practice dependent on the will of those who apply it, rather than on the law itself. Nor should it be couched in terms so vague or so general as to produce substantially the same effect in practice.'Ofcom's reprimand of Eamonn Holmes was based on a

guidance note it issued to broadcasters about the coverage of the coronavirus crisis on 23 March. On the same day the government imposed the lockdown, confining people in their homes unless they had a 'reasonable excuse' to be outside.

The right to free speech was among the few civil liberties not suspended by the government that day, but Ofcom took it upon itself to curtail it anyway. In my letter to Dame Melanie, I asked Ofcom to withdraw its reprimand of Holmes and issue a press release affirming the importance of freedom of expression, and provide assurances that in future it will not seek to stifle the expression of dissenting views about coronavirus or the government's response to the pandemic. It has not done so. Therefore, I've written

a follow-up letter - a letter before claim sent pursuant to the Pre-action Protocol for Judicial Review under the Civil Procedure Rules - asking Ofcom to withdraw its guidance note. If it does not, the Free Speech Union will ask the court for permission to apply for a Judicial Review of the guidance.

The right to free speech is one of our most precious liberties - perhaps the most precious of all - and the fact that we're in the midst of a public health crisis is a reason to protect it, not curtail it. All of us, whether scientists, politicians or ordinary citizens, are doing our best to understand the threat posed by Sars-CoV-2 and how best to minimise the harm it causes, both directly and indirectly. There are, at present, no settled views about any of these issues, certainly no consensus among scientists that can be described as 'the science'. Allowing everyone to express their views on these matters freely, without the threat of being sanctioned by a state regulator if those views happen not to accord with those of the government or other public authorities, is the best way to achieve that understanding.

Toby Young is the co-author of What Every Parent Needs to Know and the co-founder of several free schools. In addition to being an associate editor of The Spectator, he is an associate editor of Quillette. Follow him on Twitter @toadmeister

I do not have to agree with your view to defend our right to hold any view.