Layers of ball courts

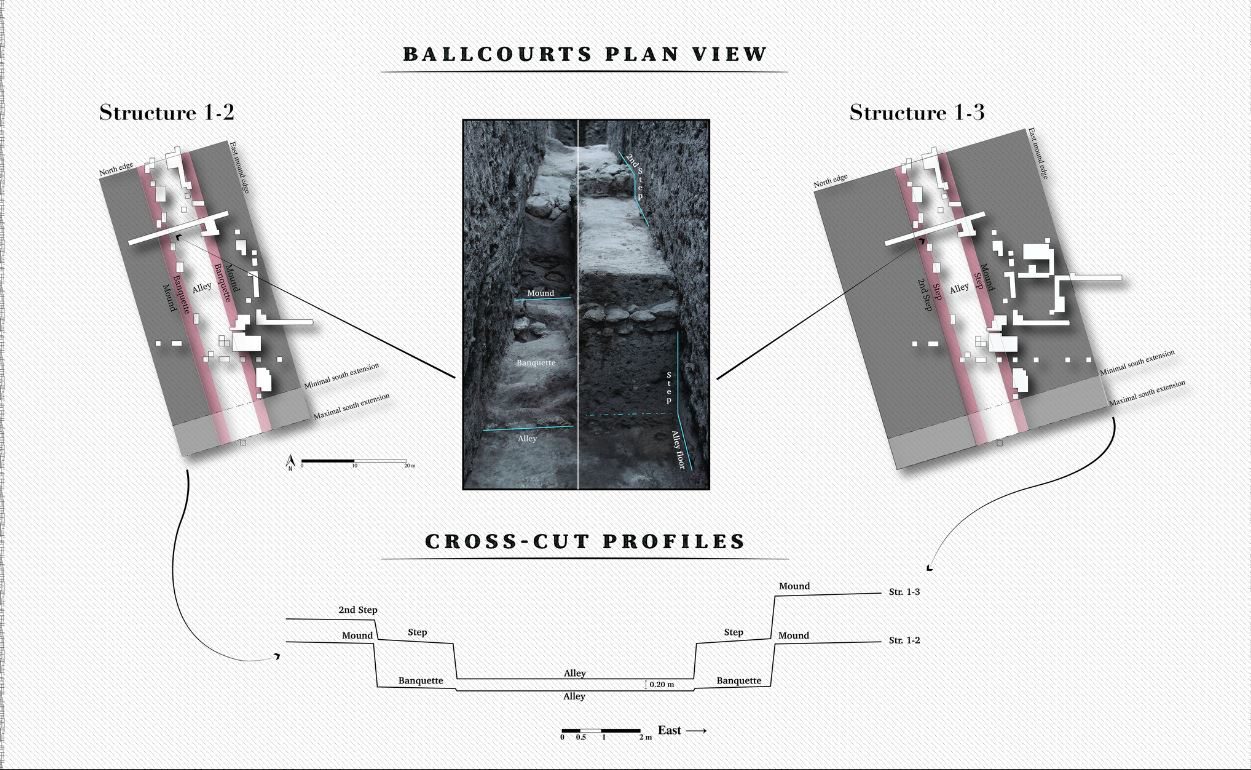

The ball court — a stone-floored alley about 50 meters (165 feet) long, bounded by steep stone walls and earthen mounds — once occupied a place of honor in the heart of the ancient city. But sometime between 1174 and 1102 BCE, the people of Etlatongo dismantled parts of the court and ritually "terminated" its life. That ceremony left burned bits of plant, mingled with broken Olmec-style pottery, animal bones, shells, and a few human bones (which may or may not have come from a later cemetery) scattered on the carved bedrock floor of the court and atop the earthen mounds that ran the length of its sides.

But beneath that 12th century BCE ball court lay another, even older one, dating to 1374 BCE. That's roughly when (as far as archaeologists can tell from the available evidence) the formal version of the game — the one played on elaborate stone courts for crowds of wealthy, high-ranking spectators in major urban centers — was still being developed. Archaeologists Jeffrey Blomster and Victor Salazar were surprised to find a ball court so old in the mountainous highlands of Mexico instead of the Olmec-dominated tropical lowlands, where archaeologists have assumed the game got started.

The oldest known Mesoamerican ball court, which dates to 1650 BCE and has a floor of compacted earth rather than stone, is at Paso de la Amada in Chiapas, on the Pacific coast of Mexico just northwest of Guatemala. Until now, it looked like people didn't start building formal stone ball courts in the Mexican highlands until almost a thousand years later. By then, the game had been fully developed and exported all over Mesoamerica — or so it was widely thought. Who invented the ball game?

This ball court challenges that assumption. Its presence means that by 1374 BCE, the game was already important enough to people in the highlands to occupy a prominent place in the city and justify the investment of resources it took to build a stone court. And that suggests that people in the highlands may also have played a role in developing its rules and the layout of the court. Blomster and Salazar suggest that ideas about the game may have passed among communities until it eventually coalesced into something that would have been recognized from one end of Mesoamerica to the other.

A modern recreation of the Mayan ball game.

The find also suggests that the ball game was already at the center of trade and interaction between regions. The customary equipment for the game was a hard rubber ball, and Castilla elastica rubber trees grow in the lowland coastal regions. That's partly why archaeologists have given the Olmec credit for inventing the game. But if the game was a major part of Etlatongo's cultural life 3,400 years ago, then there must have been trade in rubber — or more likely, in rubber balls. And the connections between communities weren't just commercial. The game itself would have linked far-flung cities and shaped their political life.

Unanswered questions

When the Etlatongo court was built, Mesoamerican society was getting more complex, and power was concentrating into a few major centers. Building stone ball courts and staging important ball games would have united communities, but those things would also have given emerging political leaders a chance to show off their wealth, power, and status.

But there's still a lot we don't know about where the Mesoamerican ball game came from. The earliest versions of the ball game were probably played in open fields, and informal games probably kept being played wherever there was open space for millennia, which means they didn't leave archaeological evidence behind. Communities like Etlatongo and Paso de la Amada didn't start building stone courts until the ball game became a major social and political fixture.

Blomster and Salazar found another structure under the 1374 BCE ball court at Etlatongo. It was once a long, narrow structure, laid out in the same direction as the ball court, and it had been incorporated into the later ball court's east wall. The first ball court's layout and alignment is clearly based on the older structure's, Salazar told Ars, but archaeologists didn't have enough time in the field to excavate enough of the older structure to say for sure whether it was an even earlier ball court. Archaeologists aren't even sure how old that earliest structure is because there was nothing associated with it that could be radiocarbon dated.

Science Advances, 2020 DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aay6964 (About DOIs).

Kiona N. Smith is a freelance science journalist at Ars Technica. She holds a B.A. in Anthropology from Texas A&M University and has written for Air & Space, Astronomy, Discover, Gizmodo, Hakai Magazine, Popular Mechanics, and the Washington Post. Follow her on Twitter: @KionaSmith07

Comment: More on the Mayans, Aztecs and the Popul Vuh: