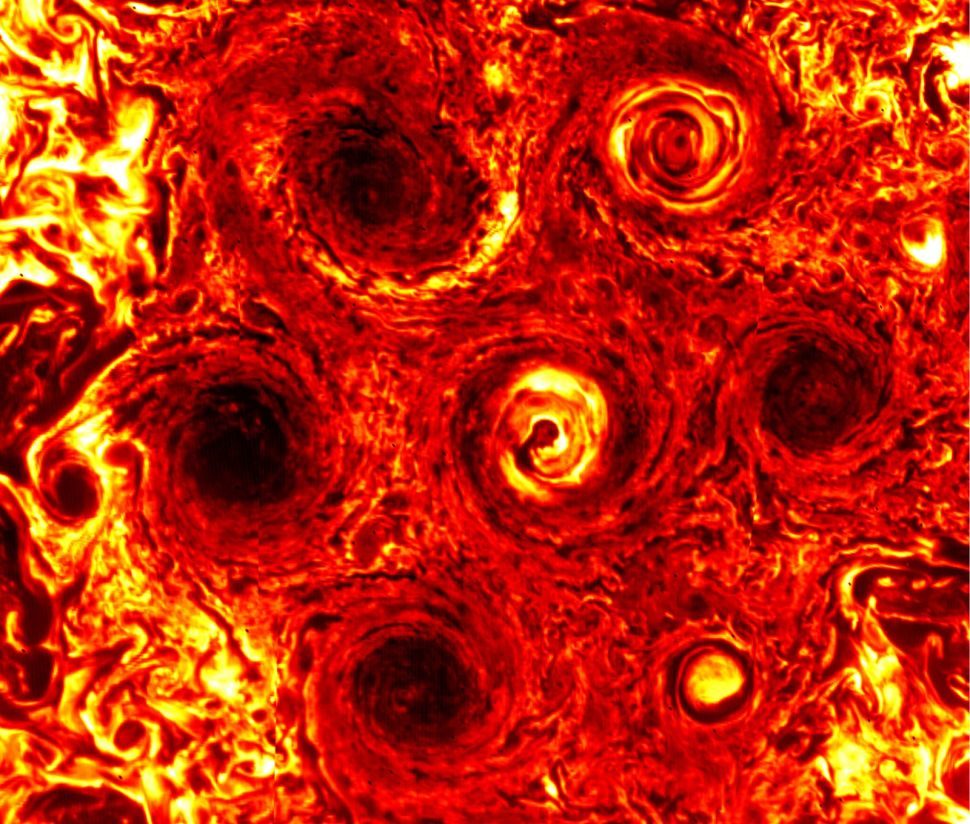

Juno spied the newfound maelstrom, which is about as wide as Texas, on Nov. 3, during its most recent close flyby of Jupiter. The storm joins a family of six other cyclones in Jupiter's south polar region, which Juno had spotted on previous passes by the gas giant. (Those encounters also revealed nine cyclones near Jupiter's north pole, by the way.)

The southern tempests are arrayed in a strikingly regular fashion. Previously, five of them had formed a pentagon around a central storm, which is as wide as the continental United States. With the new addition, that girdling structure is now a hexagon.

"These cyclones are new weather phenomena that have not been seen or predicted before," Cheng Li, a Juno scientist from the University of California, Berkeley, said in a statement yesterday (Dec. 12).

"Nature is revealing new physics regarding fluid motions and how giant planet atmospheres work," he added. "We are beginning to grasp it through observations and computer simulations. Future Juno flybys will help us further refine our understanding by revealing how the cyclones evolve over time."

Juno orbits Jupiter on a highly elliptical path every 53 Earth days, gathering most of its data when it comes closest to the giant planet. And those encounters are quite close indeed: During the Nov. 3 pass, the 22nd science flyby of Juno's $1.1 billion mission, the probe skimmed a mere 2,175 miles (3,500 kilometers) above Jupiter's cloud tops, NASA officials said.

But it took some fancy flying to make sure Juno survived the experience. The mission team determined that the probe's trajectory would take Juno into Jupiter's shadow for 12 hours on Nov. 3. And that likely would've been a death sentence for the solar-powered probe.

"We would've gotten cold. Really, really cold," Juno project scientist Steve Levin, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, said during a press conference here yesterday at the annual fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU), where the team announced the new results.

But the navigation team at JPL came up with a solution: "jumping Jupiter's shadow." On Sept. 30, Juno's handlers directed the solar-powered probe to fire its small reaction-control engines in pulses for 10.5 hours. This pushed the probe's path steadily outward — and, ultimately, out of the shadow path altogether, Levin explained.

"Without that maneuver, without the creative genius of the folks at JPL on the navigation team, we wouldn't have the beautiful data that we have to show you today," he said.

Juno launched in 2011 and arrived in orbit around Jupiter on July 4, 2016. The spacecraft is studying Jupiter's composition and gravitational and magnetic fields, among other things. The data Juno is gathering should help researchers better understand how Jupiter — and, by extension, the solar system — formed and evolved, mission team members have said.

The initial mission plan called for Juno to tighten its science orbit considerably, down to 14 Earth days. But the team called off the engine burns that would have achieved this reduction after discovering issues with the probe's fuel-delivery system. So, Juno will stay in the 53-day orbit for the duration of its mission, which currently goes through July 2021.

R.C.