Fears of explosions at the nearby nuclear energy plant flooded into his mind. Bastie, a high school biology and geology teacher, rushed outside expecting to see the bloom of a mushroom cloud. But as he soon discovered, the shaking came from something less devastating but still surprising for the region: an earthquake that cracked through the ground.

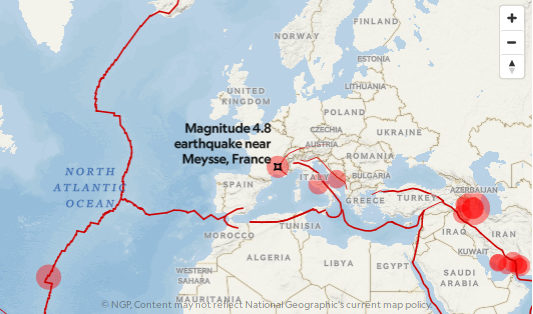

Clocking in at 4.8 magnitude, the temblor damaged numerous buildings and injured four people. It also left scientists buzzing over a number of curious features. For one, while France is no stranger to temblors, they are often quite small, explains seismologist Jean-Paul Ampuero of the Université Côte d'Azur in France. Monday's event was only of moderate intensity by global measures, but it was a "very large one for French standards," he says.

Even more surprising is that the temblor cut clean to the surface, cracking Earth's crust like an eggshell. Such breaks are common for hefty earthquakes, such as the 7.2 magnitude Landers earthquake that struck California in 1992. The formation of a surface fracture during the Le Teil temblor therefore left researchers scratching their heads, prompting a hunt for the curious quake's source.

"When an earthquake is surprising, it's a big opportunity to learn something new," Ampuero says.

Spying from the sky

Earthquakes worldwide come from the slow-motion dance of the planet's tectonic plates. These blocks of crust and upper mantle are continually jostling for position, which builds up stresses until eventually the ground breaks, sending out ripples of waves that we feel as quakes.

France's tectonics are particularly complicated. The country sits atop the Eurasian tectonic plate, which abuts the African plate to the south. But the boundary between the two is complex, and it includes a number of smaller plate fragments known as microplates. The varying movements as these blocks of Earth collide squishes France from multiple directions.

"We don't have [a] large, simple, nicely defined strike-slip fault like the San Andreas fault," geophysicist Lucile Bruhat from the Ecole Normale Supérieure in Paris says via Twitter direct message. While large earthquakes are possible here, mega-temblors like those in California are more rare.

What's more, moderate ruptures in any location don't usually fracture the surface, explains Raphaël Grandin, a geodesist at the Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris. When Monday's temblor struck, Grandin didn't expect to see any features atop the ground.

"But because it is in France, we have to [study] it," he says. "It is our country." Grandin and others began poring over radar data from satellites active during the quake, through which they can identify the minute movements of the ground's surface toward or away from the orbiting spacecraft. This produces a rainbow-colored map that portrays buckling in the landscape caused by the event.

To his surprise, a clear signal emerged revealing signs of not only land deformation, but also a surface rupture.

The reason, in part, is this quake's strikingly shallow depth. Most larger earthquakes start far below the surface, radiating from a break in the plates at least three to six miles down. But analysis suggests that this latest temblor unzipped the crust starting a mere mile or so underground.

"It's a very, very shallow earthquake, even for global standards," Ampuero says.

Near the surface, the weight of overlying rocks is lower, which means that the stresses are lower and earthquakes are usually weaker, Grandin notes. Faults also behave differently at different depths, Ampuero adds. While deep stress frequently releases with a jolt, shallow stress releases slowly over time.

"They tend to creep; they don't tend to break," he says.

Such events aren't without precedent; Grandin points to a shallow 4.7 magnitude temblor that left a crack in Australia. But they are thought to be rare, and how France's quake was both moderate and shallow remains an open question.

Comment: The Australian earthquakes referenced in the study occurred in 2005 and 2007.

Searching for a break

For more clues, researchers headed to the field on November 13, using the satellite analyses to help pinpoint the crack as it jutted across roads. Now, they're working to study the site in many ways, including installing seismometers to track the fault's activity and recording any additional signs of deformation.

Ampuero and his team also collected a fresh rock they located near the fault and plan to test its properties in the lab to see if there's anything weird that might explain the unusual break. Other scientists are now studying older satellite images of the region to suss out any past deformation that might offer more clues to the temblor's source.

One intriguing possibility has already emerged: The mystery quake might be due to quarry activity nearby, Robin Lacassin of the Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris notes on Twitter. The fault plane likely extends below the quarry, so the significant removal of rock could have reduced the normal tectonic stress in this area and forced the surface to readjust. Ampuero and his colleagues are investigating this possibility.

Perhaps no one is more intrigued by the odd event than Bastie, who lives less than half a mile from an obvious segment of the fracture, which he joined the scientists on Wednesday to explore.

"These clues of the Earth's activity, I just saw it in books ... I never experienced it in the field," he says. "It was both scary and exciting."

Comment: Just today another quake was recorded, although not in the same region, at M3.7 4 km W of Le Puy-Notre-Dame at 09:04 local time:

See also:

- Gulf Stream is 15% weaker, region south of Greenland coldest in 1,000 years

- They just keep coming: Skyscraper-sized asteroid due to pass Earth this week

- Several injured as rare 5.4M earthquake strikes southeast France - UPDATE: Earthquake revised down to 4.9M

- Southern California hit by 7.1 magnitude earthquake just one day after M6.4 tremor - the largest for 20 years

- Huge earth crack several hundred miles long opens up in Pakistan

And check out SOTT radio's:- Behind the Headlines: Earth changes in an electric universe: Is climate change really man-made?

- Adapt 2030 Ice Age Report: Interview with Laura Knight-Jadczyk and Pierre Lescaudron

As well as SOTT's monthly documentary tracking these events: SOTT Earth Changes Summary - October 2019: Extreme Weather, Planetary Upheaval, Meteor Fireballs