© JAXA

The life of an

asteroid is lonely. The rocks spend eons drifting through the cold vacuum of space.

But on Wednesday, the asteroid Ryugu welcomed a special visitor: Japan's

Hayabusa-2 probe successfully

landed on the asteroid's surface at

21:06 ET (01:06 UTC on Thursday).

The

Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) launched

Hayabusa-2 into space in December 2014. Its mission: explore and collect samples from Ryugu, a primitive asteroid half-a-mile in diameter that orbits the sun at a distance up to 131 million miles (211 million kilometers).

The probe

reached its destination in June 2018, then got to work making observations, measuring the asteroid's gravity, and rehearsing to touch down.

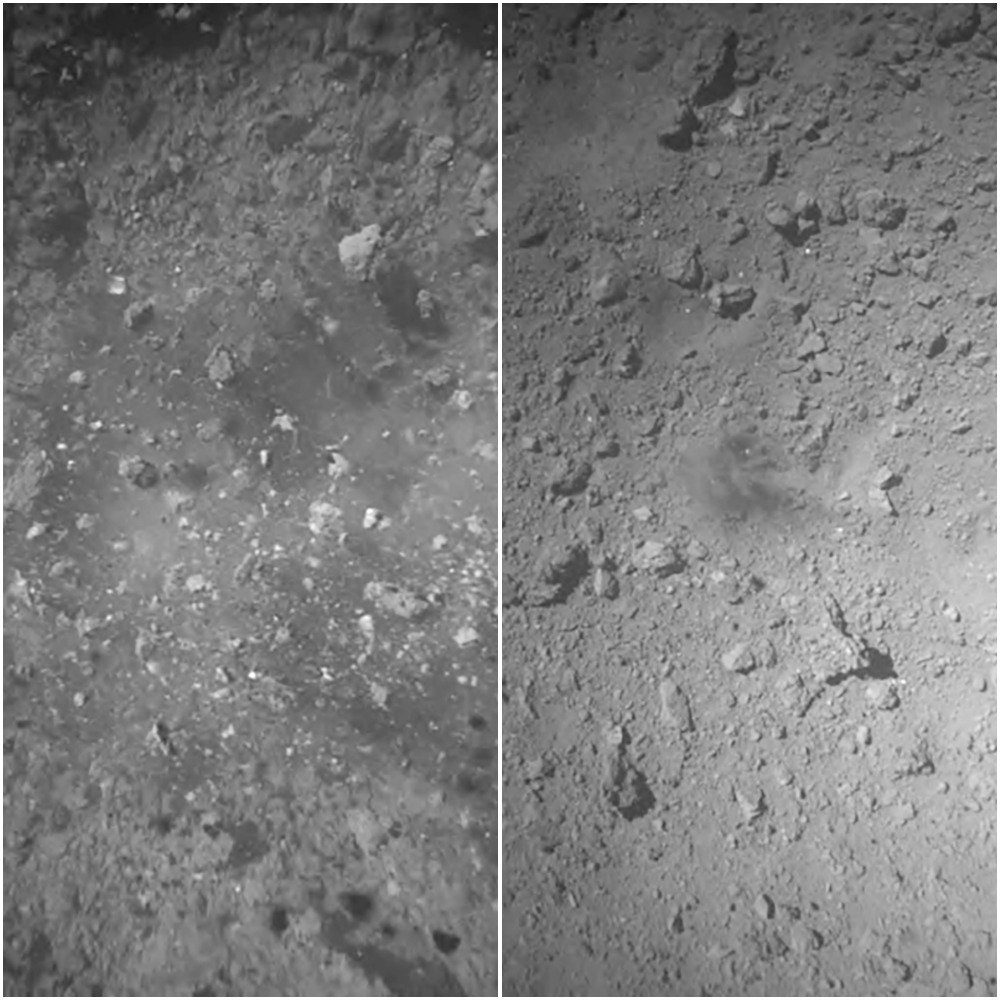

It blasted the asteroid with a copper plate and a box of explosives in April in order to loosen rocks and expose material under the surface, then successfully landed on Ryugu last night to gather up the rock and soil debris.The spacecraft captured the images below as it left the asteroid's surface.

"First photo was taken at 10:06:32 JST (on-board time) and you can see the gravel flying upwards. Second shot was at 10:08:53 where the darker region near the centre is due to touchdown," JAXA

tweeted.

© JAXA

Asteroids are made of rock and metal, and they take all kinds of quirky shapes, ranging in size from pebbles to 600-mile megaliths. Most of them hang out in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, though Ryugu's orbit sometimes takes it between Mars and Earth.

Some asteroids date back to the dawn of our solar system 4.5 billion years ago, when materials leftover from the formation of planets coalesced into these chunks of rock. In that sense, asteroids can serve as time capsules: What scientists find in those primitive rocks could tell us a lot about the solar system's history.

Ryugu is a C-type asteroid, which means it's rich with organic carbon molecules, water, and possibly amino acids. Amino acids form the building blocks for protein and were essential to the evolution of life on Earth. Some theories posit that an asteroid first brought amino acids here, gifting our planet with the seeds of life, though that's still debated.

About three-quarters of our solar system's asteroids are C-type.

Hayabusa-2 aims to be the first mission to bring samples from such an asteroid back to Earth.

The probe initially landed on Ryugu in February and collected shallow samples from just below the surface, but mission managers decided to gather some deeper rock samples as well, since that material hasn't been exposed to harsh weathering from space.To accomplish that, the probe had to lift back off the asteroid, then blast a

10-meter crater into the surface in order to access to the rock beneath.

So in April,

Hayabusa-2 released and detonated a box of explosives in space that shot a copper plate into the asteroid.

Wednesday's landing then made a splash in all that freed-up material.

© JAXA/Twitter

"These images were taken before and after touchdown by the small monitor camera (CAM-H). The first is 4 seconds before touchdown, the second is at touchdown itself and the third is 4 seconds after touchdown. In the third image, you can see the amount of rocks that rise," JAXA

tweeted.

After it touched down,

Hayabusa-2 then collected a new set of samples and left Ryugu's surface. At the end of this year, it will begin the 5.5 million-mile (9 million-kilometer) journey home.

So far, everything is

on schedule.

NASA is on a similar missionNASA is also studying a far-off asteroid.

The agency's

OSIRIS-REx mission

reached a much smaller C-type asteroid, Bennu, in August 2018. But the probe didn't land on Bennu's surface; instead, it's been orbiting at a

record-breakingly close distance.

The plan is for

OSIRIS-REx to approach Bennu's surface in July 2020, but the spacecraft will only make contact for about five seconds. During that quick instant, it will blow nitrogen gas to stir up dust and pebbles and collect the samples. If all goes according to plan, it will return that material to Earth in 2023.

The asteroid's surface has turned out to be rougher than expected, however, and debris flying off the space rock can pose a threat to the orbiting spacecraft. So NASA is still

choosing its sampling site.

But Bennu has already made a significant finding: In December, before it entered orbit around Bennu, the probe

discovered that the asteroid harbored ingredients for water (oxygen and hydrogen atoms bonded together).

Though Bennu is too small to host liquid water, it's

possible that water could have once existed on its parent asteroid, which Bennu broke away from between 700 million and 2 billion years ago.

Though NASA's asteroid-exploration mission will collect a larger quantity of sample material than Japan's, the JAXA team

hopes that comparing the samples from two different sites on the same asteroid will yield novel information about how long-term space exposure changes asteroids over time.

Both Bennu and Ryugu could also teach scientists a lot about the history of the solar system and potentially - if they contain organic materials - about the origins of life on Earth.

I hope they don't bring back samples awkwardly similar to petrified wood [Link]