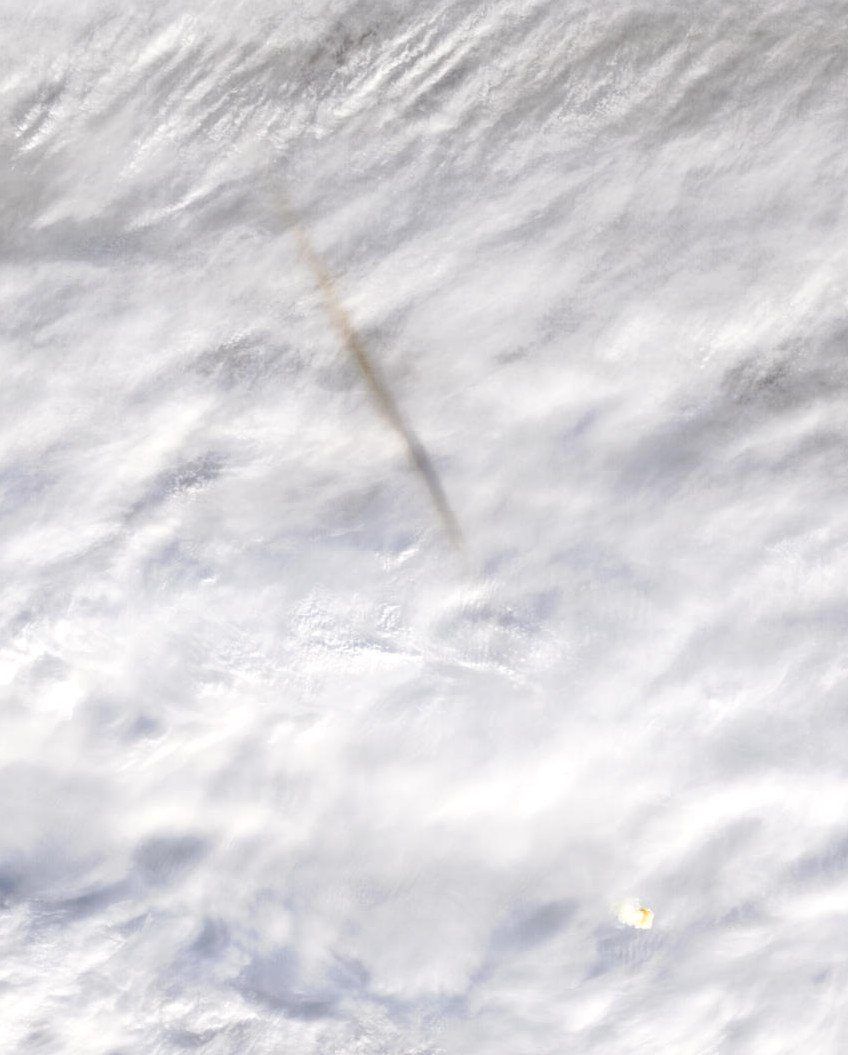

The fireball tore across the sky off Russia's Kamchatka peninsula on 18 December and released energy equivalent to 173 kilotons of TNT. It was the largest air blast since another meteor hurtled into the atmosphere over Chelyabinsk, in Russia's south-west, six years ago, and the second largest in the past 30 years.

Unlike the Chelyabinsk meteor, which was captured on CCTV, mobile phones and car dashboard cameras, the December arrival from outer space went largely unnoticed at the time because it exploded in such a remote location.

Nasa received information about the blast from the US air force after military satellites detected visible and infrared light from the fireball in December. Lindley Johnson, a planetary defence officer at Nasa, told BBC News that blasts of this size were expected only two or three times a century.

Comment: Right, except that we just had two in 6 years...

The space agency's analysis shows that the meteor, probably a few metres wide, barrelled into Earth's atmosphere at 72,000mph and exploded at an altitude of 16 miles. The blast released about 40% of the energy of the meteor explosion over Chelyabinsk, according to Kelly Fast, Nasa's near-Earth objects observations programme manager, who spoke at the 50th Lunar and Planetary Science conference near Houston.

Since the event came to light, meteor researchers have been asking airlines for any sightings of the fireball, which came in close to routes used by commercial carriers flying between North America and Asia.

Comment: Any airlines close to it would have been incinerated, or knocked out of the sky by its downward shockwave. Which, we suspect has already happened at least once in recent times:

What are they hiding? Flight 447 and Tunguska Type Events

Peter Brown, a meteor specialist at Western University in Canada, spotted the blast independently in measurements made by global monitoring stations. The explosion left its mark in data recorded by a network of sensors that detect infrasound, which has a frequency too low for the human ear to pick up. The network was set up to detect covert nuclear bomb tests.

The Bering Sea event is another reminder that despite efforts to identify and track space rocks that could pose a threat to Earth, sizeable meteors can still arrive without warning. Nasa is working to identify 90% of near-Earth asteroids larger than 140 metres by 2020, but the task could take another 30 years to complete.

The 20m-wide meteor that detonated over Chelyabinsk lit up the morning sky on 15 February 2013. At its most intense, the fireball burned 30 times brighter than the sun. The flash quickly gave way to a shockwave that knocked people off their feet and shattered windows in thousands of apartments. No one was killed but more than 1,200 people were injured, many by flying glass. Some sustained retinal burns from watching the spectacle.

In 1908 the most powerful meteor blast in modern times shook the ground in Russia. The rock exploded over Tunguska, a sparsely populated region in Siberia, and flattened an estimated 80 million trees over an area of 770 sq miles.

Comment: Raindrops keep falling on our heads...