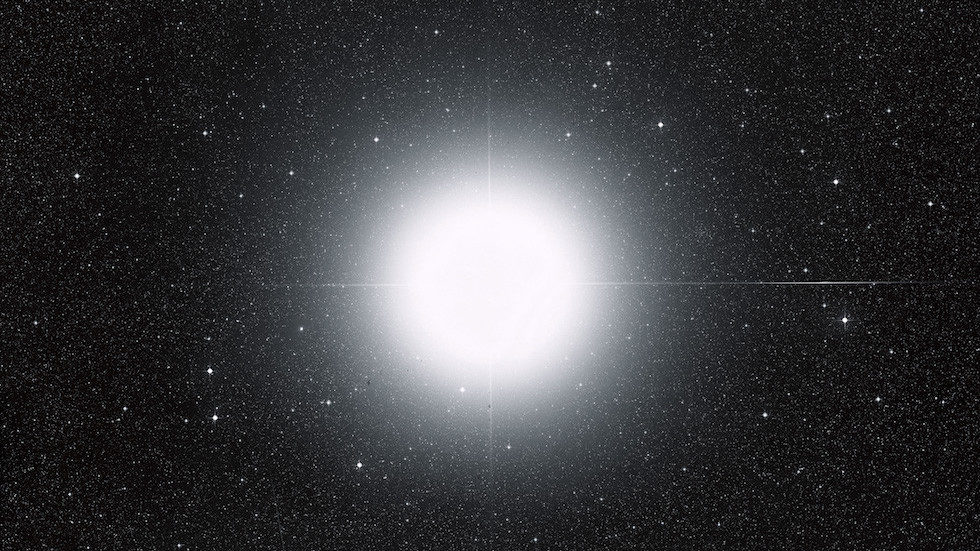

A 2.8-mile-wide (4.6km) asteroid called Jurgenstock will pass in front of the double star system Sirius on Monday night, briefly blocking its powerful shine and casting an eclipse-like shadow across Earth for approximately 20 minutes.

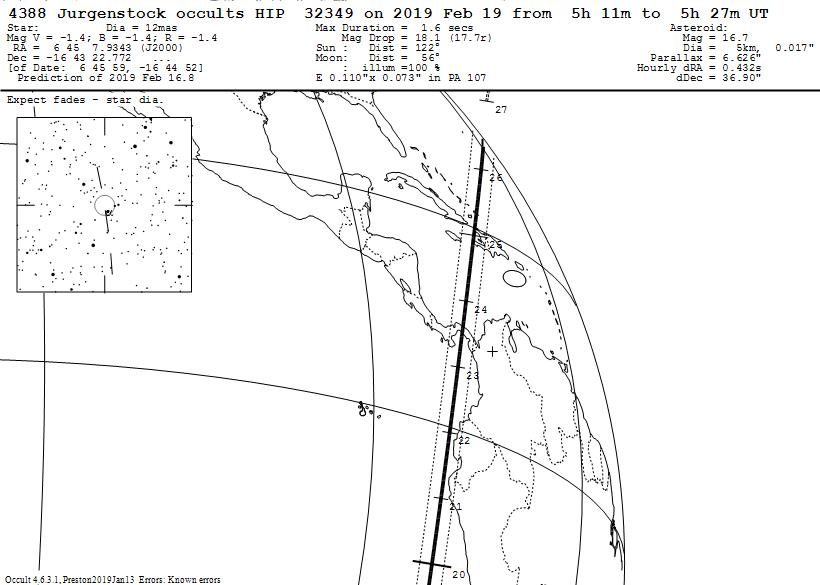

The so-called occultation will be fleetingly visible over parts of southern Argentina, southern Chile, Central America and the Caribbean at around 10:30pm MST on Monday evening. And the circumstances of the celestial event are so unusual that astronomers are issuing a strange plea to any potential witnesses.

Astronomers Bill Merline and Danib Sunham, who published a series of helpful maps illustrating the shadow's path, say anyone in the right position has a very small window to actually see the full occultation - about 1.6 seconds.

Sirius is so bright, it's difficult for scientists to track its exact movements. The occultation offers a good opportunity for astronomers to harness eyewitness evidence in helping them narrow down Sirius' location and motion.But it could be a shallow drop in brightness lasting perhaps only half a second, if you are near the edge of the path.

With such a precarious timeline for the stellar blackout, Merline and Sunham are asking stargazers fortunate enough to be in the right place to record the event with their cell phones or on video, and to give a leeway of 60 seconds before and after their scheduled time to allow for miscalculations.

"It would be best to use two cell phones, or one plus a video-capable camera, with one cell phone used to provide accurate audio time signals based on GPS, such as with the 'Time the Sat' app for Androids and 'Emerald Time' for iPhones," they wrote.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter