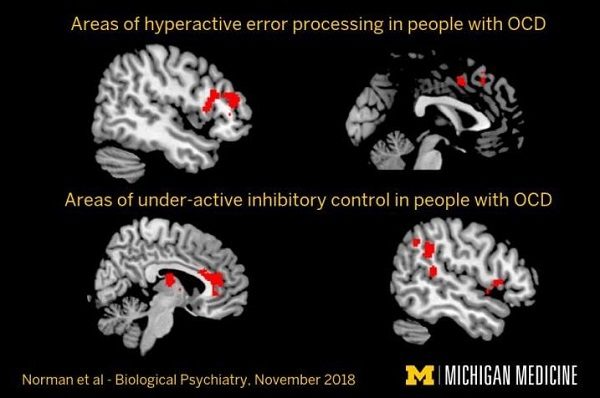

A study published in the journal Biological Psychiatry indicates such brains are too sensitive to errors and don't work hard enough to block signals that can trigger distressing symptoms.

The mental illness is characterized by repetitive thoughts, urges and mental images that can be debilitating. These can fall into obsessions, such as intrusive thoughts about taboos or germs, or compulsions such as counting and repeatedly checking on things like the front door or the oven.

The condition affects around 2.2 million Americans, according to the Department of Health, and it remains unclear what causes it. Previous research has pointed to brain abnormalities, although such studies haven't had enough participants to be conclusive, Dr. Luke Norman, lead author of the study and a postdoctoral research fellow in the University of Michigan Department of Psychiatry, told Newsweek.

The researchers studied the cingulo-opercular network: a group of brain regions tied together by nerves. This network helps our brains decide whether to tell the body to start or stop certain actions.

Similarities found in the brains of the OCD patients indicate the links between these areas may not work properly.

"The study is exciting because it suggests that OCD patients may have an 'inefficient' linkage between the brain system that links their ability to recognize errors and the system that governs their ability to do something about those errors," Dr. Kate Fitzgerald, associate professor in psychiatry at the University of Michigan, told Newsweek.

However, further research is needed to prove whether the patterns revealed in the brain scans cause the condition, or if something else is at play.

Currently, doctors either use medication such as serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) to treat the condition, assign patients psychotherapy or prescribe a combination of the two. But cognitive behavioral therapy, the most common form of psychotherapy, only works for around half of patients, according to the authors.

"This study sets the stage for therapy targets in OCD, because it shows that error processing and inhibitory control are both important processes that are altered in people with the condition," said Fitzgerald.

"For instance, rTMS [repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation] was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat OCD, targets some of the circuits that the University of Michigan team has been working to identify," said Fitzgerald. "If we know how brain regions interact together to start and stop OCD symptoms, then we know where to target rTMS."

The team is also carrying out a clinical trial for CBT for OCD. Teenagers and adults aged up to 45 both with and without the condition are invited to take part. Those interested can contact researchers at psych-ocd-study@med.umich.edu.

The take-home message, said Fitzgerald, is the condition "is not some deep dark problem of behavior-OCD is a medical problem, and not anyone's fault."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter