To do this, they've hauled up cores of sediment from the bottom of the North Sea in an area called Doggerland. It's named for the shoal called Dogger Bank in the southern part of the North Sea, which in turn is named for a type of medieval Dutch fishing boat called a dogger. The land became ice-free about 12,000 years ago, after the end of the last ice age.

More recently, about 8,000 years ago, the plateau of land between what is now the east of England and the Netherlands was flooded by the sea. This brought an end to the forests and animal life that had colonized the region from other parts of Europe, including early human communities.

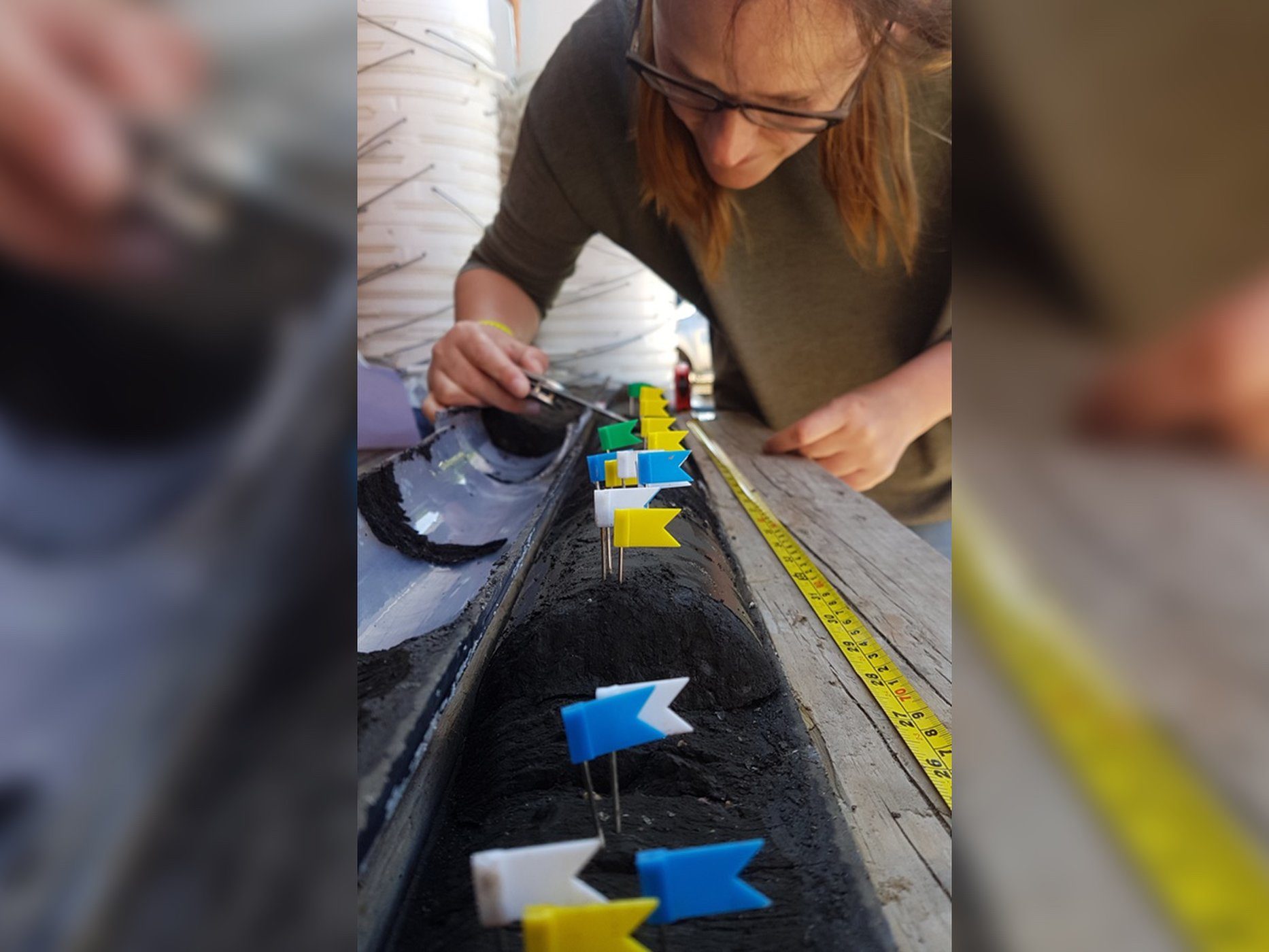

The chief marine geoarchaeologist for Wessex Archaeology, Claire Mellett, said that 10 of the sediment cores taken by an offshore wind-farm developer from the North Sea contained ancient deposits of peat. This organic material can form only in marshes on land.

Those cores are now being studied for clues about the flooded region. This research includes studies of ancient pollen grains and other microscopic fossils contained in the peat samples, which would reveal details of the landscape and climate of Doggerland before it sank.

Wind farm finds

The latest sediment cores were taken from the Norfolk Boreas site, a wind farm about 45 miles (72 kilometers) from the shore at its nearest point that covers 280 square miles (725 square km). Mellett said that the sediment cores containing ancient peat deposits covered a fairly wide area of around 32 square miles (85 square km) of the flooded Doggerland region. This was the first time that sediment cores covering such a wide area were recovered from the underwater region, she said

"The remote sensing provides us an image of the seabed, but no physical material - so when we get the cores, that gives us the actual evidence," Mellett told Live Science.

"We can see where the old rivers are. We can see the peat lands, and we can see the extent of them, so we know how big they are. We're essentially reconstructing the geography of the North Sea around 10,000 years ago," she said.

Flooded landscape The peat deposits were particularly important because they contain an environmental record of the changing landscape and climate of the area, spanning from about 12,000 to 8,000 years ago, Mellett explained.

"We also look at things like microscopic charcoal, so we can see when there has been a big burning event. We don't know whether that burning was driven by humans or whether it was a natural forest fire, but we can all see all that within these peat deposits," she said.

Some human remains - including part of an ancient skull and several human artifacts, like fragments of stone tools - have been recovered by fishing and dredging operations in the parts of the North Sea that cover the flooded Doggerland region.

The work being done by Wessex Archaeology could help scientists find more potential sites of early human habitation in Doggerland, Mellett said.

"Our ultimate endgame will be to produce maps of the area at different time periods, so we'll do one for just after the ice age. We expect it will be quite a sparse landscape without many trees, a bit like Arctic Canada today.

"And then, the trees start to come back as the climate warms. We know that the woodland was quite open and that there were wide areas where we had marshlands growing, so we'll do another reconstruction for that."

Finally, she said, "we can see when the sea level starts to rise and the area floods. And then you get drowning of the area. You get tidal creeks, and you get bits of coastline."

One of the lasting mysteries of Doggerland is just how quickly the region flooded, and the sediment studies by Mellett and her colleagues will try to answer that question.

"The life span of the people at this time was about 30 years, so [even] if sea level was rising, they probably wouldn't have been able to observe it," Mellett said. "But in geological history, it's one of the fastest-rising sea levels that we've ever experienced."

It might have taken only a few centuries for Doggerland to go from a forested plateau to being completely covered by the sea: "[it was] less than 1,000 years, and it might be closer to 500 years," she said.

No mention of Atlantis

YET!