Somebody had to be keeping tabs, right?

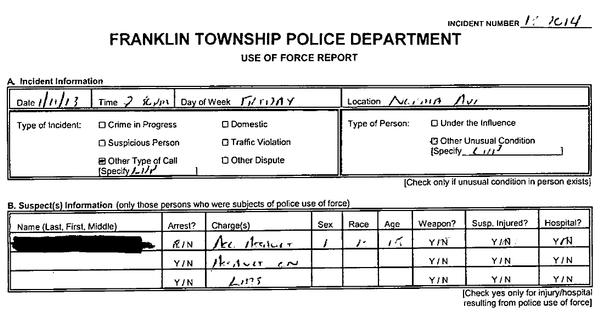

Almost two decades ago, the state Attorney General's Office ordered police officers in New Jersey to document every single time they used force against another person. The goal was to make sure nobody with a badge abused the greatest authority granted them.

The timing was no accident: The state was reeling from one embarrassing episode after another of racial profiling and controversial shootings. The public was losing faith.

In response, state authorities could show they were keeping watch, creating an encyclopedia of the most mundane and most violent arrests. The documents would be reviewed by superior officers, and annual reports would be sent to county prosecutors and the attorney general.

They also envisioned something far greater: a statewide database that would flag bad officers and identify others who needed intervention. It would inform policy changes and improve training. It would bolster public confidence.

Policing in New Jersey would forever be changed.

Fast forward 17 years: The force forms, if completed at all, are tucked in filing cabinets and stashed away in cardboard boxes in every corner of the state. They are rarely closely examined, current and former law enforcement officials say. Thousands of them are incomplete, scrawled in illegible handwriting or even quarantined because of mold.

Taken together, they are a monument to two decades of failure to deliver on a system that promised to provide analysis, oversight and standard practices for using force. Worse, the central system that would flag potentially dangerous cops for review was never created.

So we built one.

The Force Report, a 16-month investigation by NJ Advance Media for NJ.com, is built on five years of data and 72,607 pages of documents. It details every reported incident of force from 2012 through 2016, the most recent year of data available for the state's 468 local police departments and the State Police.

The resulting analysis reveals troubling trends that have escaped scrutiny. Just 10 percent of officers accounted for 38 percent of all uses of force. A total of 296 officers used force more than five times the state average. And across New Jersey, black people were more than three times as likely to face police force than white people.

Comment: The other 90% have a moral obligation to band together & defend the public against the 10%. There's no excuse.

These statistics are at the heart of stories to come for the next few months as The Force Report morphs into the most comprehensive examination of police use of force ever undertaken in New Jersey. As part of that effort, NJ Advance Media is making its entire database available to the public, letting anyone search by officer name or town, and ask questions similar to what reporters and editors have been asking for the past year.

How, for example, did a patrolman in Millville, a small city in South Jersey, report more uses of force than nearly any other cop in the state? Why did police in the leafy suburb of Maplewood report using force at a rate higher than Newark, Camden or the New Jersey State Police?

And why had the Attorney General's Office, which over the years improved standards for investigating high-profile police shootings and investigating officer misconduct, all but given up on using this data for oversight?

Using force is a normal and necessary part of policing, but it's also one of the most serious ways officers can abuse their power. Excessive force causes needless injuries, erodes public trust and can cost taxpayers millions of dollars in lawsuits.

Until recently, many departments refused to hand over the use-of-force forms without redacting officer names and other key details, making it impossible for outsiders to see which officers used the most force. That changed in 2017, when a landmark state Supreme Court ruling ordered police to release the complete forms to the public.

That's when we went to work.

Using the state Open Public Records Act, NJ Advance Media filed 506 requests for use-of-force forms covering every municipal police department and the State Police. The news organization spent more than $30,000 to extract the information from those paper records and build an electronic database detailing five years of punches, takedowns and shootings.

"That's exactly the kind of analytics that we wanted to have when we initiated it," said John Farmer Jr., the former state attorney general who enacted the first policy requiring use-of-force reporting in 2001.

"The intent of requiring these reports was to enable police executives, police management and, ultimately, the AG's office to figure out what's going on and, frankly, undertake the kind of analysis you're undertaking," Farmer said.

"I'm half-kidding, but you really have done their job for them."

Newark Public Safety Director Anthony Ambrose said officials at every level in New Jersey have been "asleep at the wheel," failing to scrutinize use-of-force trends and outliers.

"It was being recorded, but if the data is not being looked at or an analysis isn't being done, then why are we capturing it?" Ambrose said.

Presented with an overview of NJ Advance Media's findings, current Attorney General Gurbir Grewal promised to overhaul the system. That includes fixing New Jersey's early warning system announced earlier this year and creating a statewide, electronic database of force.

He declined, however, to say exactly how the reforms would be implemented, or when.

"The hoops you had to jump through to get this data are completely unnecessary," said Grewal, who took office in January. "It shouldn't have taken you a year and 500 OPRA requests, and we're committed to making this data more available, not just to the media but to the public.

"Folks have a right to know this information."

MAKING A PAPER TRAIL

New Jersey's use-of-force reports are born from bloodshed. You can trace their history all the way back to a spate of police shootings on the state's highways.

Farmer, who was named attorney general in 1999, was sworn in just one day after police killed a Morristown man, Stanton Crew, after a car chase along Route 80 in Parsippany. A year earlier, the term "racial profiling" entered the mainstream amid scrutiny of a State Police shooting involving four young black and Hispanic men on the New Jersey Turnpike.

Authorities were under public pressure to make sure the investigations were above board. But when they tried to review cases, Farmer said, "it was difficult because of the absence of any kind of paper trail."

His office assembled a committee to recommend reforms.

One year later, the committee released a 10-page document that forever would change how New Jersey officers tracked force. The new template required details such as the name, age, race and ethnicity of the officer and suspect. But it also required officers to log every twist of the arm, kick in the ribs or use of pepper spray.

The primary reason for the forms was in the state's self-interest, to create a written record in case lawsuits or citizen complaints arose. But officials also saw them as a data source to inform better policing, allowing for intervention and potentially preventing problems, said Wayne Fisher, now a criminal justice professor at Rutgers University, who chaired the committee as deputy director at the state Division of Criminal Justice.

"The numbers in and of themselves rarely provide a clear conclusion about use of force," Fisher said. "But it is an indicator of agencies and officers who deserve scrutiny."

Fisher said that while the attorney general has the authority to order every department in the state to fill out the forms, the office doesn't control local budgets.

So as departments across the state installed sophisticated computers in their patrol cars and mounted cameras on their uniforms, the reports themselves stayed analog. Many were handwritten, stored as faded carbon copies or created on a computer only to be printed out and filed away in hard copy.

Grewal, the current attorney general, said it was always within the office's power to fix it -- it just never did. Digital reporting should be a "no-brainer" in 2018, he said, noting that his office maintains secure online portals for police agencies to input other kinds of data.

"The way our system is structured in New Jersey, with the attorney general having oversight of law enforcement, I think that gives us the ability to require this kind of reporting," he said. "We should be able to analyze it in a hundred different ways to identify patterns, and we're committed to doing that."

A PATCHWORK OF POLICIES

Most oversight of local police departments in New Jersey falls to the state's 21 county prosecutors. They are appointed by the governor and answer to the attorney general. The same is true for monitoring use of force, resulting in a decentralized and patchwork system.

Prosecutors are primarily concerned with whether an officer did anything illegal, current and former law enforcement officials said, and few offices perform the kind of analysis that would identify trends or prevent problems.

"They'll prosecute the egregious case, but for every egregious case, there's probably a whole lot more on the fringes that needs to be addressed that don't get addressed," said Jon Shane, a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City and former Newark cop.

Cumberland County Prosecutor Jennifer Webb-McRae said her office receives only aggregate numbers from local departments, relying instead on other indicators in her county's early warning system to detect troubling trends.

"I'm not saying that it's not laudable to look at the data, and maybe as a result of what you're giving me, we might take a closer look at that," Webb-McRae said. "But we focus on the incidents we're dealing with and how we can improve based on the specific facts."

Officials in only six of the state's 21 counties said they maintained copies of all use-of-force reports from the local departments they oversee, but NJ Advance Media found entire towns missing from troves of reports turned over by county prosecutors in response to records requests.

Most counties primarily rely on superficial, one-page annual summaries that don't drill down into which officers are using force, or against whom. Even in offices that do monitor every use-of-force case, problems easily slip through the cracks.

A 2008 memo from the Passaic County Prosecutor's Office to police chiefs chided "some departments" because their forms "have not been consistently filed" as required by the state.

In Union County, authorities said they review every form -- about 900 per year -- from the county's 21 departments. But NJ Advance Media's review found hundreds of reports filed in Elizabeth, the county's largest city, that had not been signed by a department supervisor.

Even Grewal, the current attorney general, said that during his time as Bergen County prosecutor, inconsistent reporting practices and vague state guidelines made use-of-force forms useless as an oversight tool.

"Our county prosecutors are the chief law enforcement officers in their county, and it's their obligation to supervise law enforcement operations in their counties, which includes prosecuting and investigating crimes but also ensuring that officers are trained properly and that they're acting properly in their counties," he said.

"So it's incumbent on me to give them the tools to do that. They haven't had those tools."

He said prosecutors should use The Force Report database to identify and investigate potential problem areas.

LACKING 'EARLY WARNINGS'

Without meaningful checks at the county level, local departments are left to do the bulk of monitoring. The quality of oversight varies dramatically there, too.

After two Bloomfield officers, Sean Courter and Orlando Trinidad, went to prison for falsifying records related to an excessive force case, the department hired outside supervisors to review reports, as well as dashboard and body camera footage, every time one of its officers uses force.

"Those two cops were beyond aggressive out in the street and clearly should have been flagged and weren't," said Police Director Samuel DeMaio, who was brought on in the aftermath of the scandal. "They sit in prison today because the department failed them."

In Middlesex County, a Carteret officer accounted for one-fifth of all uses of force by officers in the 50-person department over a two-year period. But that pattern never came to light until after the officer, Joseph Reiman, was indicted on accusations of assaulting a teenager after a brief car chase.

Reiman has denied any wrongdoing. The case has yet to go to trial.

In March, the Attorney General's Office announced a major overhaul of the state's oversight of police, requiring all departments to implement "early warning systems" to identify potentially problematic officers for intervention, training and, if necessary, discipline.

The system requires departments to monitor its rank and file for 14 various red flags such as misconduct, lawsuits, domestic abuse and drunken driving. But the directive does not require any analysis of use-of-force trends. Only instances ruled excessive by a court or an internal investigation, a process that can take months or years, must be considered.

Experts said that was hardly an "early warning" for one of the greatest powers given to police.

"That's dumb," said Seth Stoughton, a former police officer who teaches law at the University of South Carolina. "It is. By the time you get to an excessive force complaint, the problem has already manifested."

Many departments voluntarily monitor uses of force as part of intervention systems to comply with national accreditation standards. In New Jersey, while attorney general directives are mandatory, the accreditation is voluntary, and fewer than half of the state's departments have or are in the process of obtaining it, according to the New Jersey State Association of Chiefs of Police.

Stoughton said most uses of police force are legally justified but that even repeated instances of legal force might call for policy changes in a given unit, shift or department.

"You look for things that can be signals -- not definitely are signals, but can be signals of problems," Stoughton said. "When you get a red flag, the red flag is to draw your attention to the officer so you can figure out if they're going to be a potential problem.

"It's not rocket science here," he said. "We're talking about Supervision 101."

In an interview earlier this week, Grewal said state authorities were "revising the directive as we speak" and considering additional metrics.

"Departments were free to do more - and already do," Grewal said. "I can tell you with the State Police, with our early warning system, we do look at all use-of-force reports in our early warning system, and any two use-of-force reports will trigger a review. With respect to including it in the directive, I wouldn't foreclose us from adding it.

"It's a process," the attorney general said. "I don't have all the answers now."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter