DePuy, owned by Johnson & Johnson, would not say how much it had handed over, but it could run into millions. It recalled a metal-on-metal hip system in 2010 after it emerged that debris from wear and tear was causing damage and resulting in a large number of surgical revisions.

The company withdrew the products - a range known as the ASR (articular surface replacement) system - and advised that patients should have tests to check cobalt and chromium ion levels in their blood and, in some cases, MRI scans or X-rays.

Many patients have had follow-up operations to remove the defective hips and replace them, and the NHS is continuing to monitor others.

Johnson & Johnson told the Guardian it had made payments towards the costs. A spokesperson said: "Under the ASR hip system reimbursement programme ... DePuy Synthes has provided reimbursement to the NHS trusts and other healthcare providers for applicable testing and treatment, including expenses related to revision surgeries."

The ASR system was approved for use in Europe in 2003, but was not used by the NHS until the following year. By the time it was withdrawn it had been used in about 10,000 patients.

When approved by European regulators it had not been tested in humans, but had been subject to extensive laboratory and simulator tests.

The problems with metal-on-metal hip replacements have been highlighted in a joint investigation involving the Guardian, the BBC and other members of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ).

The Implant Files project traces how issues began to emerge not long after the medical journal the Lancet described total hip replacement as "the operation of the century", with the potential to transform millions of lives.

While many replacement hips performed well, problems emerged with two new procedures that involved metal parts.

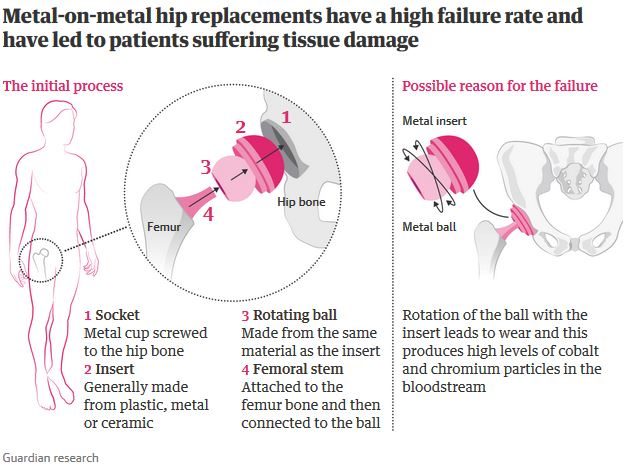

One procedure involved a total hip replacement, whereby a metal ball and stem were attached to the thigh bone, and a metal cup attached to the pelvis.

The other was the hip resurfacing system. For this, the ball of a patient's hip joint was retained, but a metal cap was put over its surface. This then sat within another metal cap on the pelvis.

In the UK, Midland Medical Technologies (MMT) was the first to bring this procedure to the market with its Birmingham Hip Resurfacing (BHR) system, which was launched in 1997. MMT was bought by the UK medical equipment firm Smith & Nephew in 2004 for £67m.

After the success of this implant, DePuy brought its own version to the market in 2003. Its metal-on-metal resurfacing won approval in Europe on the basis of laboratory testing, including the use of simulators, rather than through clinical trials on people.

One retired hip surgeon, who did not use the ASR system, said people would visit his clinic asking for the treatment after hearing about it from friends or adverts.

"At the time, I think we were all amazed how quickly the ASR and large head metal-on-metal hip replacement was taken up throughout the UK and in fact around the world," said Keith Tucker, a retired surgeon who is chair of the Orthopaedic Data Evaluation Panel.But in 2007 the Australian Orthopaedic Association national joint replacement registry noted that ASR seemed to have twice the risk of revision - the need for further surgery - compared with other resurfacing procedures.

"Resurfacing seemed to have become very fashionable and often the demand was driven by patients who had heard about it from various sources."

The following year, the registry published data showing some women undergoing metal-on-metal hip resurfacing were facing more follow-up operations than others.

In 2010, DePuy withdrew its implants after the National Joint Registry (NJR) for England and Wales shared data showing higher than expected revision rates among patients with metal-on-metal hips.

Within five years of receiving DePuy's resurfacing device, 12% of patients had undergone revision surgery, and within five years of having an ASR total hip replacement the figure was 13%.

DePuy's spokesperson said the company had carefully analysed the data from Australia and communicated with surgeons about which patients should receive the ASR hips.

"DePuy constantly reviewed and evaluated surveillance data concerning the ASR hip system from a variety of sources, including national joint replacement registries, internal complaints data, peer-reviewed published literature, company-sponsored clinical trials, and external clinical research reports, as we do with all of our products," the spokesperson said.In the years that followed, other manufacturers withdrew from the market as more data showed the high level of follow-up surgery needed by patients.

"Until August 2010, when DePuy announced the voluntary recall, the totality of the data available to DePuy indicated that the revision rate of the ASR hip system was similar to that reported for other large diameter metal-on-metal monoblock and resurfacing hip devices."

In 2015, Smith & Nephew advised that its BHR system should not be used in females or in men needing the smaller-sized implants.

A spokesperson for the company said the data did not indicate there was a single, dominant reason why the revision rate was higher in these patients. "For instance, in various registries, there are a range of fairly typical diagnoses, including infection, dislocation, metal sensitivity, loosening/lysis and fracture," the spokesperson said.

In the US, patients who have faced further surgery as a result of problems with metal-on-metal hips have been awarded damages, but in the UK there has not been a successful court case.

This year, a UK judge found against patients who were seeking compensation from DePuy after experiencing problems with a different metal-on-metal hip it made. The patients' lawyers claimed high revision rates recorded in the NJR were a sign of problems with the product.

However, DePuy argued the issues were a result of a "nocebo effect", where patients who had seen that the hip had been recalled had experienced problems as a result of their negative expectations of the implants.

Several other cases against manufacturers are in the balance as lawyers work out if there is any chance of them succeeding.

Tim Annett, a partner at the law firm Irwin Mitchell, said the bar had been set very high by the high court. "You would have to show that the risk is significantly higher from these hips [than for other hips], and possibly double, although this was not confirmed by the ruling."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter