The Congress of El Salvador agreed in April to extend the authority of jailers to keep gang leaders in solitary confinement. Over the next five days, the two reigning street gangs killed more than 100 people.

With the highest homicide rate of all countries in the world, El Salvador is a nation held hostage.

Law-enforcement officials estimate that one gang, MS-13, operates an extortion racket with little pressure from authorities in 248 of the 262 of the country's municipalities. It battles for neighborhood control with another gang, Barrio 18, which runs its own protection scheme in nearly as many regions.

Politicians must ask permission of gangs to hold rallies or canvass in many neighborhoods, law-enforcement officials and prosecutors said. In San Salvador, the nation's capital, gangs control the local distribution of consumer products, experts said, including diapers and Coca-Cola . They extort commuters, call-center employees, and restaurant and store owners. In the rural east, gangs threaten to burn sugar plantations unless farmers pay up.

Latin America accounts for 8% of the world's population and a third of its homicides, which makes it one of the world's most murderous regions. At its violent core is El Salvador, where an imported American gang culture rivals government authority, and its leaders hold sway with a surplus of money, guns and willing young men.

Unlike the major drug cartels that for years produced much of the region's violence-using murder in the service of selling marijuana, cocaine and heroin largely to Americans-gangs in El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala profit from extorting their own neighborhoods.

The gangs have evolved a more violent, chaotic economic model, one that is advancing in drug-trafficking countries, including Mexico, where large cartels have splintered into many warring groups.

"We've left behind the era of the cartel and the kingpin," said Alejandro Hope, a security consultant in Mexico City. "Today, most violence in Latin America is the result of a new system that's more diverse, harder to control, and much more local."

While drug cartels collect profits from customers abroad, with dollars and euros trickling into local communities, these gangs steal from their own people. Documents collected in a recent federal investigation in El Salvador found that MS-13 earns as much as $600,000 a month in extortion payments from bus companies, retailers and other businesses. The payments range from a few dollars a day on each vehicle operated to hundreds of dollars a month charged to vendors in public markets.

Drug enforcement officials said El Salvador's gangs earn about $20 million a year from extortion, with an estimated $3 million coming from businesses in San Salvador's historic center. The gangs also sell drugs and stolen cars, adding to the revenue from legitimate businesses they have seized.

Cementing their national role, MS-13 and Barrio 18 may be El Salvador's largest employers. The defense ministry estimates the gangs hire as many as 60,000 people as lookouts, collectors and assassins. By comparison, the two largest private employers, underwear makers Hanesbrands Inc. and Berkshire Hathaway's Fruit of the Loom, together employ about 20,000.

A 2016 study commissioned by the country's central bank estimated the economic cost was more than $4 billion a year, or roughly 16% of gross domestic product. That accounts only for law enforcement, medical bills, property damage and lost investment.

San Salvador's homicide rate of 95.7 killings per 100,000 people makes it the world's sixth-deadliest city. Across the capital, municipal workers scrub gang graffiti from walls as fast as it appears.

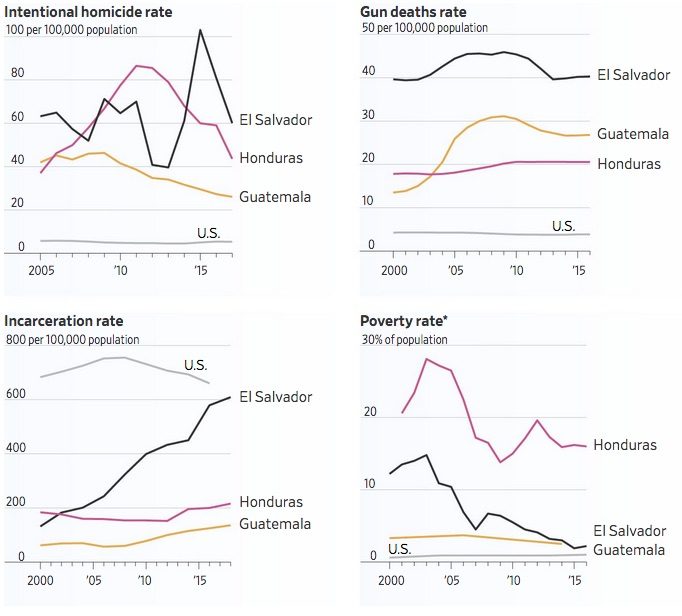

Gauging the Misery of Countries Gripped by Gangs

Street gangs in El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala profit from extorting businesses and residents in their own neighborhoods. The protection rackets are enforced with violence and threats of violence that far exceed U.S. levels.

Sources: Igarapé Institute; FBI (intentional homicide rate); Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (gun deaths rate); World Prison Brief (incarceration rate); The World Bank (poverty rate)

The plight of Salvadorans is one explanation for the steady stream of migrants north. Thousands seek to enter the U.S. each year, either by petitioning for asylum or by crossing the border illegally. Researchers found most are propelled by fear of violence. Mexico and U.S. immigration officers apprehended 335,545 Salvadoran migrants from 2014 to the end of 2017, according to government data.

José Gualberto Claro Iglesias, a 48-year-old trucker from Suchitoto, a former Spanish colonial town in central El Salvador, sent his wife and four children to Los Angeles in 2015, after the family narrowly survived an attack by MS-13 members. The gang set fire to his pickup truck while Mr. Claro and his family were inside because he had refused to make extortion payments.

In August 2017, Mr. Claro tried to cross the U.S.-Mexico border near El Paso, Texas, to reunite with them. He was caught and held nearly 13 months in a U.S. immigration detention center before he was deported. He owns three properties and two 18-wheeler container trucks in El Salvador. He plans to sell them to pay for a move to Panama, where he will bring his wife and children.

"As a worker and as a human being, you can't live in this country in peace," Mr. Claro said. "You spend all your time and energy trying to defend your business and your family."

The Dr. Jose Antonio Rodriguez Porth Scholastic Center, an elementary school, sits on a dirt road lined with open sewers in Comunidad Iberia-on the fault line between two neighborhoods, one controlled by MS-13, the other by a faction of Barrio 18.

Across the street is a national police post. A few blocks away is La Tiendona, the city's largest wholesale market, which police allege is the source of roughly $300,000 a month in extortion payments made to Barrio 18 by fruit and vegetable vendors.

On a recent morning, as students in blue-and-white uniforms kicked around a soccer ball, school principal Amilcar Rivera described their prospects. Many of his students, he said, start working for one or the other gang as lookouts when they are as young as 10 years old.

"The only opportunities they have are working at the market nearby, where they can unload or load trucks. It's either that, or they can join one of the gangs," Mr. Rivera said. "You can earn $300 a week doing manual labor, or you can get $1,000 a week from extortion. Which one do you think these young people will choose?"

The choice is stark in a weak economy. One-third of Salvadorans live in poverty, according to World Bank data, meaning they earn less than $5.50 a day. The average annual growth of the national economy, which relies on coffee, sugar and textiles exports, has been about 2.5% for the past 25 years, slower than most developing nations.

Brutal crimes by MS-13 members in the U.S. attracted the attention of President Trump, who has promised to expel them. Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced in October a new task force to take them off the streets.

The reach of the gangs in the U.S.-they are found mostly in Central American immigrant neighborhoods in California, New York's Long Island, Maryland and Virginia-doesn't compare with their dominance in El Salvador.

"It's not the same here as in the U.S.," said René Del Cid, 25, who was deported to El Salvador from Frederick, Md., in December 2017. Police pulled him over for a traffic violation while he was driving with an expired license. He had lived in the U.S. since he was 11. As an adult, he worked on landscaping crews and as a parking-garage attendant.

When he returned to El Salvador, Mr. Del Cid got a job fielding customer service complaints for banks at a call center in downtown San Salvador. He lived with relatives in a Barrio 18-controlled section of San Vicente, a city about 40 miles away. He took three buses in a circuitous three-hour commute to avoid passing through areas controlled by rival gangs.

In March, MS-13 gunmen stopped his bus and demanded to see the ID cards of riders. When they saw that Mr. Del Cid lived in Barrio 18 territory, the gang members pulled him off the bus. They held him at a house for nearly three weeks, he said, demanding ransom money and threatening his life.

Mr. Del Cid was able to phone an MS-13 member in Maryland, a man he had befriended at an immigration detention center. The friend negotiated his release. By then, Mr. Del Cid had lost his job and the $200 hidden in his sock.

"Everywhere I go I'm a target," he said. "If I join the gangs, I'll die either by them or by the police."

Manuel de Jesus has Barrio 18 tattoos covering his chest, arms and neck, marking a decade in gang life that, he said, was now behind him. He credits the church, which now provides a place to live for him, his wife and children. Gangs keep growing with recruits from home and abroad, he said: "The U.S. is deporting a ton of people to here. They're just reinforcements."

These same gangs had their origins in Los Angeles. MS-13 and its rival Barrio 18 were founded in the 1980s and 1990s by refugees of El Salvador's 12-year civil war. When the conflict ended in 1992, Salvadorans lost their protected immigration status, and thousands of gang members in U.S. prisons were deported.

Comment: And which Western government was largely responsible for screwing things up so badly in El Salvador?

Once in El Salvador, dozens of autonomous "cliques" operated under the loose direction of gang leaders. Over the next two decades, the rapidly expanding gangs gained influence, eventually co-opting politicians and judges.

Drug cartels have historically put a premium on profits, which acts as a check on random violence. Street gangs are bound by allegiance to their clique, a neighborhood group that operates largely on its own. Common killings include suspected informants and police - as well as people caught in the wrong place at the wrong time.

In a measure of the gangs' power, the president of El Salvador, Mauricio Funes at the time, brokered a 2012 truce with MS-13 and Barrio 18 to reduce the killings. Under the deal, the government moved leaders from solitary confinement and maximum-security penitentiaries to more permissive detention. Gang leaders were allowed to communicate with the outside world as well as order deliveries of food, alcohol and visits by prostitutes.

By the next year, the national homicide rate fell by 42%. Business leaders, lawmakers and many voters said the ruling leftist FMLN government had bowed to the same threats used by gangs to terrorize neighborhoods.

"The government's credibility was destroyed by the truce," said Martín Rogel, an auxiliary judge who sits on El Salvador's Supreme Court. "It was as if Salvadorans stopped believing in God. Salvadorans have stopped believing in the rule of law."

Under pressure from the U.S., the government ended the truce after a little more than a year. Murders spiked almost immediately. By 2015, El Salvador's homicide rate hit 103 per 100,000 residents.

It has since fallen but remains the world's highest. El Salvador, a country of 6.6 million people, had a homicide rate last year of 60.1 per 100,000 inhabitants, nearly 12 times the rate in the U.S., according to the United Nations.

Earlier this year, the former mayor of Apopa, José Elías Hernández, became the first municipal leader convicted of gang corruption, prosecutors said.

Mr. Hernández, who was sentenced to 12 years in prison, was found guilty of funneling money to Barrio 18 leaders and allowing the group to use municipal ambulances for private transportation, court documents said. Gang members were hired to manage garbage collection and a city property office.

Mr. Hernández, a member of the right-wing Arena party, denied wrongdoing, saying he was targeted by the ruling FMLN party.

During the killing spree that followed the April decision over solitary confinement, authorities pulled two bodies from a ditch in Apopa, a densely populated suburb of San Salvador.

The two young men, ages 17 and 23, were apparently abducted on their way to play in a soccer game, police said. They were each stabbed 20 times with a Phillips-head screwdriver.

"When you see a killing with this many wounds, when one shot would do the job, it means that the gangs wanted to send a message," said Dr. Juan Carlos Durán Chavarría, the coroner who examined the bodies.

Killings over the law extended through summer. On July 20, agents from the national police intercepted a cellphone call between an imprisoned MS-13 leader and one of his lieutenants outside. The message instructed gang members from nearly a dozen MS-13 cliques to pick three police officers or soldiers to assassinate, according to a report viewed by The Wall Street Journal.

The following month, three officers were killed, including Elmer Mauricio Beltrán, a 43-year-old father of two who lived in the rural town of San Rafael Cedros. He had worked for the national police since he was 19.

Police told his widow, an elementary school teacher, that four gunmen had surprised her husband, jumping out of a car while he chatted with friends outside a convenience store. The friends escaped unharmed.

No arrests have been made. The slain man's brother, Raúl Beltrán, also a police officer, said he always carries a gun, even into the shower at home.

"The gangs kill with total impunity," he said.

- Juan Forero contributed to this article.

Either you make business in "he local way" or you go out and make your own locality with its own rules.