At first blush, they show Vladimir Putin in a very negative light that may shock the reader. A more careful scrutiny of Browder's case shows it to be a disingenuous, baseless smear, which further begs the question: if this is the best (worst) Browder can offer as proof against Putin, the ceaseless assertions of his corruption amount to what, exactly?

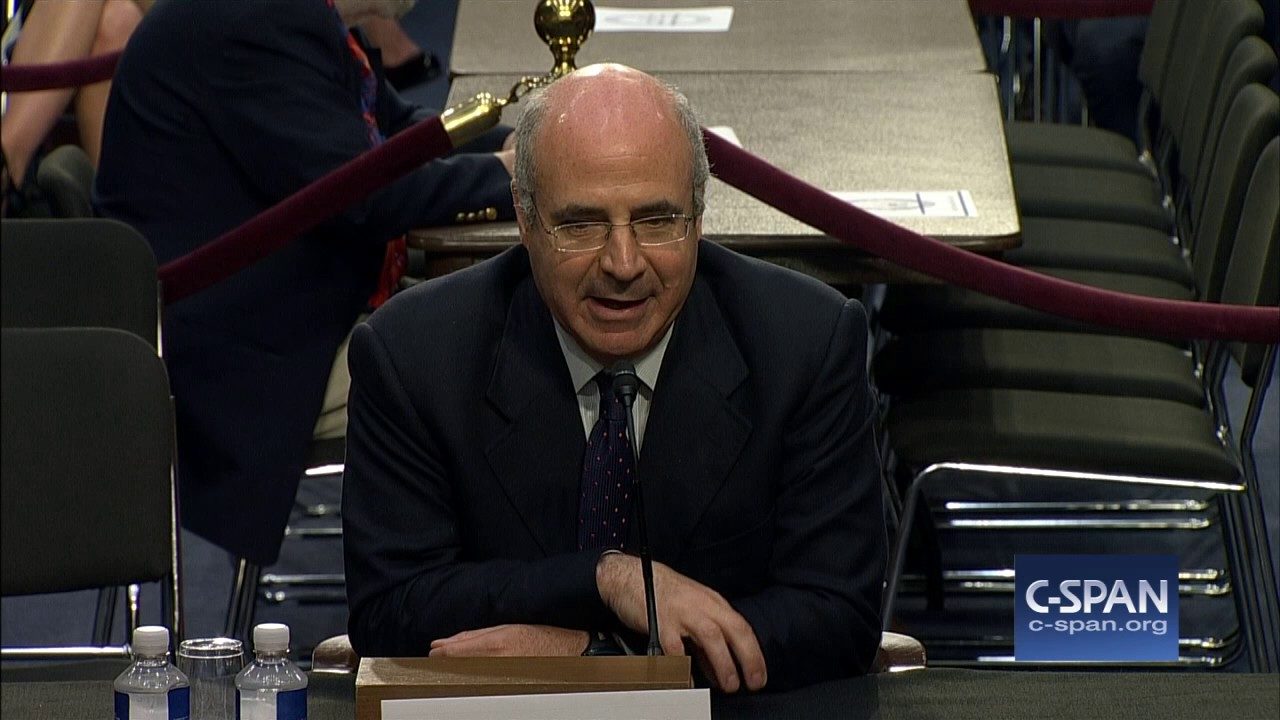

The following excerpt from my book (currently banned, but available here in electronic format) examines the merits of Bill Browder's assertions.

Chapter 19After I read this chapter the second time, I wrote the following in my notes: "Upon closer scrutiny, this chapter is an ugly, vulgar, deceitful write-up where a lot of stuff is distorted and contrived in a deceitful and malicious way... it must have been the work of a ghost-writer."

In this chapter of Red Notice, Browder gives us a shockingly crude account of the way Vladimir Putin abuses his power in Russia for his own personal enrichment. He does so right after telling us an unrelated story about himself, his own Jack Ryan1 moment of sorts.

On a cold Saturday in February 2002, while running late to his tennis game, Browder saved a man's life. As he sat in the back seat of his car holding hands with his fiancée, he saw "a large, dark object in the middle of the street." His driver Alexei drove fast, but as they approached the object Browder saw that it was a man lying in the road, cars swerving around him. He shouted, "Alexei, stop!" But as his Russian driver wasn't slowing down, Browder shouted, "Goddamnit, stop!" Browder then jumped out of the car and knelt next to the man amidst cars "zipping by and horns honking." It turned out that the man had an epileptic attack and to get him out of danger Browder put his arm under one of the man's shoulders and with his fiancée's and driver's help moved him to the side of the road.

This story - whether true or invented - serves two important purposes. First, it creates a contrast between Browder and his surroundings: he acts decisively to save a stranger's life while indifferent Russians speed by, "horns honking." When the police arrive, they virtually ignore the epileptic man and want only to blame and punish somebody for something. "For the average Muscovite," explains Browder, "a single act of Good Samaritanship could lead to a seven-year prison sentence. And every Russian knew this." Russians, it seems, must be scrupulous never to commit acts of Good Samaritanship lest they end up in a gulag. Russia, you see, is just such a horrid place.

The second reason for this digression is for Browder to make himself likeable. If you have ever studied the psychology of persuasion, you may have learned that you are much more likely to persuade an audience if you can get them to like you. Thus, Browder tells us how he saved a man's life and goes on to further garnish his image of a moral hero by explaining his investigation of Russian corruption as more Good Samaritanship: you see, he was working selflessly, risking his life to fight corruption simply to help make Russia a better place. The fact that this work turned out to be so very profitable for him was perhaps just a fortuitous coincidence. Browder strains to make himself so very likeable and trustworthy to the reader because he is about to make an incredible and utterly vicious accusation against Vladimir Putin. It is an accusation based - as he himself admits it - on nothing but his own speculation.

After priming his readers' credulity with all this self-aggrandizement, Browder ambushes them with his fantastically ugly smear of Vladimir Putin. He recounts the story about the October of 2003 arrest of Mikhail Khodorkovsky, Russia's richest man. Browder's feelings about the arrest were mixed: in Russia, rich people didn't tend to spend much time in prison, and if Khodorkovsky "miraculously stayed in jail and this was to be the beginning of a crackdown on the oligarchs, it meant that Russia had a chance at becoming a normal country." As we now know, Khodorkovsky stayed in jail for nearly ten years, and that really was the beginning of a crackdown on the oligarchs. But Browder explains it otherwise: it was no crackdown after all. "It all came down to the personal negotiation between Vladimir Putin and Mikhail Khodorkovsky, a negotiation in which neither law nor logic played any role."[2]

Browder then asks rhetorically: "Why was Putin doing this?" The likeable hero of his own story then explains: after Khodorkovsky's arrest, other Russian oligarchs essentially wet themselves with fear and "one by one" went to Putin to ask what they could do to make sure they also didn't end up in prison. "I wasn't there, so I'm only speculating," says Browder, but he imagined that "Putin's response was something like this: 'Fifty per cent.'" He further clarifies that it wouldn't be 50% for the government or for the presidential administration but 50% for Vladimir Putin personally. "I don't know this for sure. It could have been 30 per cent or 70 per cent or some other arrangement." Or it might have been zero percent. Or it might be that all these oligarch meetings with Putin only took place in Browder's own vindictive imagination.

The allegation that Russia's president used his power to extort the country's oligarchs for his private gain is an extremely serious one. It is much too serious to be based on, "I'm only speculating..." Another reason why this shot up a red flag for me was that just in the preceding chapter Browder boasts about how he and his team were able to piece together asset transfers and ownership for any company or individual stockholder because Russia was "one of the most transparent places in the world."

Because he smeared Putin in this way, Browder also needed to explain why he was such a big Putin supporter before he got expelled from Russia. At that time, he believed that Putin was acting in good faith to clean up the country because his own experience confirmed as much: after exposing corruption at Gazprom, Vladimir Putin fired and replaced Gazprom's top management. When Browder exposed how the CEO of UES (United Energy System) was selling company assets to his friends at huge discounts, Putin's government halted the sales. When he outed the Sberbank management for similar misdeeds, Russia changed its laws to disable such management abuse.

So if Putin's government in actual deed cracked down on oligarchs and worked to restore Russia to the rule of law, what made Browder change his mind about Vladimir Putin? For one thing, he may have been vexed about his expulsion from Russia. But he contrives a different explanation - one that frankly insults the average reader's intelligence. You see, after Khodorkovsky's arrest, Bill Browder continued with his activist investing: buying shares in companies and then investigating and exposing corruption of their management. But now - since Putin was appropriating large chunks of Russian economy for himself, Browder wasn't merely going against a gaggle of corrupt managers - now he was going against Putin himself.

How does that make any sense at all? Browder's activism resulted in a cleanup of corruption at Gazprom, carried out by Putin's government. This led to a hundredfold increase in Gazprom's share price. Similar actions with other firms probably led to similar outcomes. If these firms were now Putin's personal fiefdom, Browder's activism would result in an exponential rise in Putin's wealth. In effect, Putin's and Browder's business interests would be so beautifully aligned that Putin should have made sure that Browder stayed in Russia forever to work his magic unmolested. He might even have offered to hire Browder himself. At the very least, he should have provided him full protection. But no - Putin has him expelled instead.

Thus in the same chapter, Browder shows Putin to be brazenly greedy and also not greedy. Well, if Putin wasn't acting out of personal greed, there could be two other explanations for Browder's expulsion from Russia. One would be that Vladimir Putin is spectacularly stupid. The other, that Browder was actually found in violation of Russia's laws and was expelled to disable his activity. As even my Golden Retriever now understands, Vladimir Putin is far from being a stupid man and Bill Browder is far from being the moral, law-abiding hero he impersonates.

Notes

[1] Second lieutenant Dr. John Patrick "Jack" Ryan, a CIA agent, is the quintessential American hero created by author Tom Clancy in his novels. Ryan is an intelligent, courageous and moral hero committed to fighting against evil forces in the world. His heroics inspired a number of successful Hollywood films.

[2] Browder has to convince his readers that these supposed negotiations were void of logic because his own allegations in fact make no logical sense.

About the author

Alex Krainer is a hedge fund manager and author of one book on commodities trading and one book which was recently banned from publishing in the land of free speech. It is now available online in electronic format under the title "Grand Deception: The Browder Hoax." Paperback version will soon be in distribution through traditional channels.

R.C.