Yet one of Washington's most dangerous volcanoes remains the least-monitored and the least-studied in the Cascade range.

Tucked deep inside its namesake 566,000-acre wilderness a scant 70 miles northeast of Seattle, Glacier Peak is the state's hidden volcano. At a modest 10,541 feet, its summit doesn't tower over the landscape like Rainier, Baker or Adams. Settlers didn't even realize it was a volcano until the 1850s, when Native Americans told the naturalist and ethnologist George Gibbs about a small mountain north of Rainier that once smoked.

Geologists have since discovered that Glacier Peak is one of the state's most active and explosive volcanoes, said Seth Moran, scientist-in-charge at the U.S. Geological Survey's Cascades Volcano Observatory. Its most recent eruption, about 300 years ago, was a small one.

But since the end of the last ice age, the volcano has erupted repeatedly in at least six episodes - including two outbursts five times bigger than the blast that blew Mount St. Helens apart on May 18, 1980.

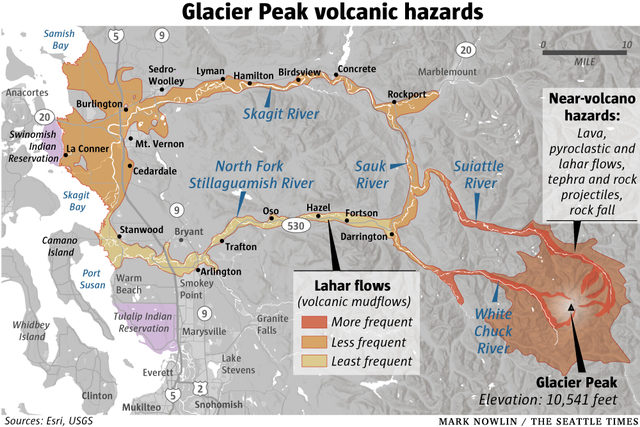

An eruption of that scale today would bury nearby communities like Darrington and Rockport under slurries of mud and debris called lahars. Roiling columns of ash more than 100,000 feet high would disrupt air traffic across the region, while sediment-laden floods could reach the Puget Sound lowlands and possibly even threaten Interstate 5.

The USGS ranks Glacier Peak among the country's highest-threat volcanoes. But the only monitoring is done by a single seismometer southwest of the summit - far less instrumentation than on any other Cascade volcano. The agency also has yet to complete a geologic map of the area, Moran said.

The problem is partly lack of money and staff, and partly because Glacier Peak is so hard to get to, he explained. Because it's in wilderness, geologists have to pack in all their gear - then pack out heavy rock samples.

Hiking in to a base camp takes nearly two days, then it's a cross-country scramble to reach remote ridges and valleys in search of signs of past eruptions.

"It's a lot of forcing your way through the devil's club and dense forests and navigating really, really steep terrain," Moran said.

The USGS hopes to install four additional seismometers soon, while ongoing geologic field studies aim to fill in gaps in the volcano's eruptive history. But the agency estimates it needs at least a dozen instruments on Glacier Peak to effectively track the tiny earthquakes and ground motion that can signal an impending eruption, Moran said.

Progress could be accelerated if Congress approves the Volcano Early Warning and Monitoring Bill sponsored by Sen. Maria Cantwell, D-Wash. The bill, which passed the Senate last week, would authorize $55 million over the next five years, partly to modernize and expand monitoring at Glacier Peak and other volcanoes.

Sponsored in the House by Alaska Rep. Don Young, the bill would fund volcano research and establish a center to track data from volcanoes around the clock.

"The safety of our communities is paramount, and our legislation will ensure we have the science, technology and monitoring needed to keep people informed and safe," Cantwell said in a statement.

In addition to explosive eruptions and lahars, Glacier Peak's repertoire includes formation of lava domes, parts of which collapsed repeatedly during past eruptions to form scorching avalanches of rock and debris called pyroclastic flows. The flows incinerate everything in their path - which makes Glacier Peak's lack of close neighbors a good thing.

The thick vegetation that covers the mountain makes it hard to trace the path of past pyroclastic flows and lahars, so the USGS commissioned lidar, or laser mapping, that was finished in 2016.

The technique digitally strips away vegetation, revealing the bare landscape. Features like lahars and lava flows pop out with unprecedented clarity, Moran explained.

The resulting maps underscore the risk to the Stillaguamish and Skagit Valley communities closest to the mountain, many of which were built on the thick deposits left by past lahars. In a worst-case eruption, debris flows or their muddy remnants might reach as far as Arlington, Stanwood, Mount Vernon and La Conner, according to USGS analyses.

As scientists assemble a fuller picture of Glacier Peak's hazards, officials in Snohomish County have been working to raise awareness and reduce the danger, where possible.

The county requires anyone who wants to build in the danger zone to sign a disclosure that makes it clear the property is "subject to periodic and potentially life-threatening destructive mud, water and debris flows."

Over the past year, emergency managers posted the first education and warning signs in the Darrington area. They plan to install more in the near future, said Dara Salmon, deputy emergency management director. County residents can also sign up to get emergency alerts for a wide range of natural disasters, including eruptions and lahars.

"I think awareness is higher than it used to be," Salmon said, "But we still have a ways to go."

Comment: As many in the vicinity of Hawaii's Kilauea have discovered, it's one thing to be aware of the potential activity of a volcano and it is extremely mportant to closely monitor the situation, because when it begins to unleash its fury the only choice you have is to get out of its way. And when we consider volcanic activity appears to be on the increase, now more than ever do citizens need to be ready: