It's an easily manifested suspicion I suppose - not altogether incorrect - given the commonality of misconduct in high places. And surely it's the kind of thing we'll be hearing a lot more of in years to come, after the presidency of the human cynicism factory known as Donald Trump comes to an end.

Still, and however prevalent personal duplicity may be, even at six I understood that the "everyone does it" defense wasn't exactly compelling. Not because I was a particularly developed moral philosopher, but because it never seemed to work when I would try it on my mom, in those instances where a friend and I would be playing ball and break something on the porch of a neighbor's apartment.

Whenever I tried the old "but Billy was playing too" defense, it would be met with the same reply. As I recall it involved something about a bridge, followed by a query as to whether, were young William to leap from it, I would follow him in the manner of a damned fool.

This tendency to excuse one's own misdeeds - or the misdeeds of others you admire - by way of the "everyone does it" defense is nowhere more maddening than when applied to our nation's founders, or early American presidents and prominent citizens.

Our desire to glorify these leaders is so great that any attempt to condemn or even harshly criticize them for things like slaveholding or involvement in indigenous genocide is regularly met with the same apologetics. Namely, we shouldn't be too hard on them because they were "products of their time," and shouldn't be judged by the moral standards of today, or something to that effect.

However phrased, this is really just another version of the "everyone does it" excuse. As in, "back then, everyone thought that way" (about the legitimacy of human bondage), and most prominent people participated in these evils, precisely because they weren't yet viewed as evil.

Which is all fine and good until you remember that actually, enslavement and extermination campaigns were viewed as evil, first and foremost by those who were the targets of each.

In other words, the "everybody back then felt that way" argument presupposes by definition that the feelings of non-whites don't count. Some folks always knew mass murder and land theft were wrong: namely, the victims of either. That lots of white folks didn't hardly acquits them in this instance. It's not as if the human brain was incapable of recognizing the illegitimacy of killing and enslavement.

Additionally, the belief that killing and stealing are wrong hardly emerged only in the modern era, seeing as how prohibitions against both were inscribed on those stone tablets God supposedly handed down to Moses. In other words, the founders don't merely offend by today's moral standards; they offended by moral standards that are literally ancient.

But there's something else troubling about this kind of argument: the kind that seeks to paper over past crimes against humanity by insisting we can't judge those in the past by today's standards. Namely, there were also whites in the days of the founders, or later during the days of men like Andrew Jackson, who opposed the extermination of native peoples, and who supported the abolition of slavery. In other words, even using the fundamentally racist limitation suggested by the apologists as to whose views matter, it is simply not the case that all whites stood behind racist land grabs, killings and the ownership of other human beings.

That so few know of the history of white resistance and allyship is as tragic as it is infuriating. Because the history of white dissent from the crimes of our kinfolk is so rarely told, too many of us become invested in a view of history that is thoroughly bound up with the narratives and interpretations of elites. So not only is the history we remember a white history, it is a very specific, narrow and cramped white history at that, which normalizes contributing to the death and destruction of racial others as something quintessentially white, perhaps even the essence of whiteness.

But of course there is another history, and however much white antiracism has been quantitatively less frequent than white racism, it is still vital to learn of this history so as to put an end to the excuse making for those who chose to oppress others, as well as to point to a different set of role models whose vision young whites might choose to follow.

We should know about the group of whites in the Georgia territory, led by James Oglethorpe, who petitioned the King of England to disallow the introduction of slavery there, because they considered it morally repugnant and shocking to the conscience.The list, however much longer it should be, is far longer than most probably realize. And every single one of them gives the lie to the apologists' position that somehow the morals of the day excused the racist depredations of people like Andrew Jackson.

We should know of 18th century white abolitionists like Anthony Benezet, Benjamin Lay, or the Quaker John Woolman, who pushed the larger Quaker community to a more consistent anti-slavery position than it had previously embraced. Or Thomas Paine, the famous pamphleteer and author of Common Sense, who was an ardent abolitionist, and who condemned so-called Christians for their support of the slave system.

We should know of 19th century white anti-slavery leaders like William Lloyd Garrison, who moved from advocating gradual emancipation to radical abolition, and Abby Kelley, who joined him in advocating not merely for an end to enslavement, but also for full civil rights for blacks. So too, we should study the lives and examples of abolitionists and equal rights militants, Sarah and Angelina Grimke.

We should study the example of William Shreve Bailey, who was harassed in the mid-1800s for his opposition to the Fugitive Slave Act, and for operating an abolitionist paper in the heart of a Southern slave state. That Bailey and all these others existed gives the lie to the notion that Southern slaveowners and defenders of slavery can be excused, because, after all, "that's just how everyone felt back then."

Or what of George Henry Evans, leader of the Workingmen's Party, who published a newspaper defending Nat Turner's rebellion at a time when most whites viewed Turner's insurrection as among the most vile acts imaginable? That Evans existed gives the lie to the notion that whites can be forgiven for their racism at that time and in that place.

Or Lydia Marie Child, who penned the first anti-slavery book in the United States, and who discussed the connections between racial enslavement and white male domination of women.

We should follow the uncompromising example of John Fee, a radical abolitionist preacher, dismissed from his pastor's position by the Presbyterian Synod for refusing to minister to slaveholders, and who helped to found interracial Berea College in 1858.

Or Robert Flournoy, a Mississippi planter who quit the Confederate army, and encouraged blacks to flee to Union soldiers: an act for which he was arrested. Flournoy, whose name is known by almost no one it seems, also published a newspaper called Equal Rights, and pushed for school desegregation at the University of Mississippi a century before it would finally happen.

Or Ohio politician Charles Anderson who spoke out against what he called the "myth of Anglo-Saxon supremacy," as well as the material manifestations of that myth, including slavery and conquest of much of Mexico in the 1840s.

Or the celebrated writer, Helen Hunt Jackson, who railed against Indian genocide and the repeated violation of treaties made with Indian nations by the U.S. Government.

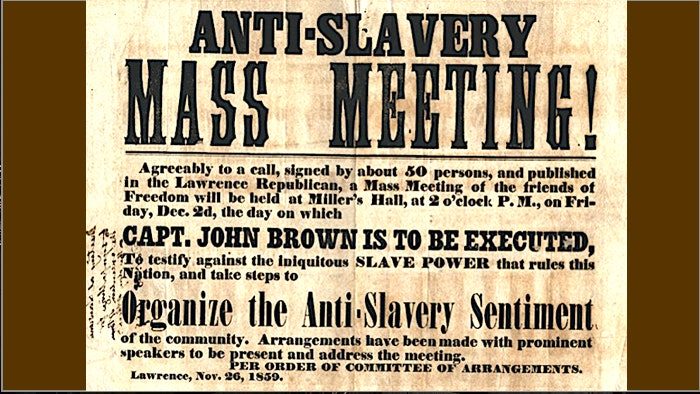

We should remember the name and story of Jeremiah Evarts, who gained prominence as a fierce and fiery critic of Andrew Jackson's policy of Indian removal from the Southeast. And of course, John Brown, who was willing to engage in armed insurrection to overthrow slavery and smash the larger system of white domination that he and his family viewed as fundamental evils.

To be sure, not every one of these persons was free of racist sentiment, and not all of them actively opposed both slavery and Indian genocide (some, rather, chose to focus their ire on one or the other), but all of them suggest that there was not only one way of thinking about either of those subjects, even among whites, to say nothing, of course, of indigenous peoples or African Americans themselves.

To accept the idea that the nation's founders should only be judged by the moral standards of their own time is to ignore that there has been no single set of morals accepted by all, at any point in history.

The victims of human cruelty have always known that what was being done to them was wrong, and have resisted oppression with all their might. As well, some among the class of perpetrators have seen clearly to this fundamental truth. And their lives and perspectives give the lie to the arguments of those who would rather excuse murderers and tyrants than praise true heroes.

One cannot emulate role models about whom one has never even heard. That so few have heard much (if anything) about the men and women above - while having to learn multitudinous details about American leaders who defended and participated in slavery and genocide - calls into question what kind of role models America prefers. And why.

Tim Wise is an antiracism educator & author. He tweets @timjacobwise, podcasts at Speak Out With Tim Wise.

My greatest heroes aren't musicians artists actors politicians but my immediate family and friends.

Nope just the propaganda about all our privilege and mistreatment to everybody else.. Boo