Steering his white Dodge Ram while wearing a tan knit cap, a drab green Carhartt coat and a smear of brown livestock feed on his cheek, Terry Goodin jounced over frozen-hard mud toward his 100 head of beef cattle. "Make sure they're all four legs down and not four legs up, in this kind of weather," he told me in his southern Indiana drawl. The temperature overnight had dipped toward zero. Now, midmorning, it stood at 16 degrees. On the rear of his old pickup truck was a "Farmers For Goodin" bumper sticker, and rattling around his head were thoughts of what he was going to say the following week in a starkly different setting -- up in Indianapolis, at the regal limestone capitol building, in his introductory speech as the leader of his caucus in the state legislature.

He wanted to talk about the importance of public education, affordable health care and a living wage, and the moral necessity of addressing the opioids scourge. Six days later, dressed in a sharp suit and a striped tie, he would stress those priorities -- and also deliver a declaration of identity:

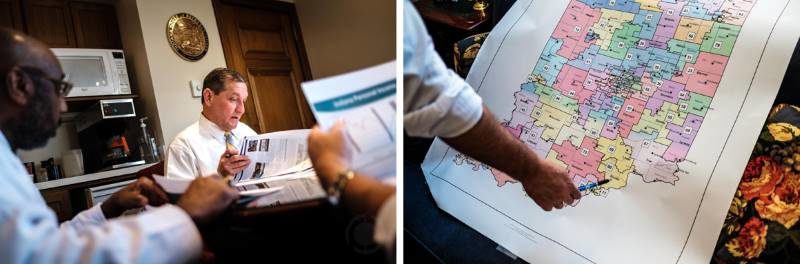

"I am a Democrat. I am a Democrat from rural Indiana."That Goodin, 51, who has held political office for more than 17 years, felt the need to say this out loud speaks to the divisions bedeviling the Democratic Party. A father of three and the superintendent of a 500-student school district, Goodin is the last Democrat in Indiana who represents an entirely rural area. A member of the Indiana Farm Bureau, the National Rifle Association and the Austin Church of God, he's an anti-abortion, pro-gun, self-described "Bible-poundin', aisle-runnin'" Pentecostal. This unusual profile for a Democrat makes him a species nearing extinction within the national party, but it's also the very reason he keeps getting reelected here. This paradox is why he is prominently featured in a report set to be made public Thursday by the leadership PAC of third-term congresswoman Cheri Bustos.

The report, "Hope from the Heartland: How Democrats Can Better Serve the Midwest by Bringing Rural, Working Class Wisdom to Washington," lands at a moment, of course, when Democrats are riled up with activist energy but also wrestling with themselves about the direction of their party -- their most reliable areas of support having receded to cities, coasts and college towns. In contrast, this report is based on interviews with 72 Democrats who hail from none of those places but rather largely agricultural, blue-collar areas in the vast, eight-state center of the country. It will be distributed to local and regional party leaders as well as the most important Democrats on Capitol Hill. Bustos shared an early copy exclusively with POLITICO.

Bustos, although she remains relatively unknown nationally, in 2016 was reelected handily in her northwest Illinois district, which Donald Trump won, too. That accomplishment earned Bustos a bigger role in Washington. She's the co-chair of the Democratic Policy and Communications Committee for House Democrats and the Chair of Heartland Engagement for the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee. Her implicit task: to translate the desires of disaffected, rural, working-class Democrats who live where she lives back to the party's distant Beltway leadership. But nobody at the DPCC or the DCCC or the Democratic National Committee commissioned this report. Bustos did. And she did it because she believes Democrats won't win back control of Congress until they win back the trust (and the votes) of rural people in Middle America.

The facts are harsh. "The number of Democrats holding office across the nation is at its lowest point since the 1920s and the decline has been especially severe in rural America," Bustos writes in the report. In 2009, the report notes, Democrats held 57 percent of the heartland's seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. Now: 39 percent. In 2008, Barack Obama won seven of the eight heartland states. In 2012, he won six. In 2016? Trump won six. There are 737 counties in the Midwest-Trump won all but 63 of them. "We can't keep bombing in the rural parts of these states," Bustos told me. And with arguably some of the most critical midterms in American history less than 10 months away, the 2020 presidential election already looming and redistricting control on the line, Democrats need to find a fix fast, said Robin Johnson, a Bustos adviser and consultant who teaches political science at Monmouth College in Illinois and conducted the interviews for the report last summer. "If we don't get this right in the next two cycles," he told me, "we're done" -- rendered mostly powerless in Congress and in heartland state houses. He called the report "a cold reality check."

From the Appalachian regions of Ohio to the Iron Range of Minnesota and the northern reaches of Michigan and Wisconsin, across Iowa and Missouri and through the southern swaths of Indiana and Illinois-areas in which Bill Clinton triumphed and Hillary Clinton tanked -- the quotes from the 72 rural Democrats Johnson interviewed read like a pent-up primal scream. And Terry Goodin's comments pop out in particular. In the report, he says the Democratic Party is "lazy," "out of touch with mainstream America," relying on "too much identity politics" where "winners and losers are picked by their labels." The Democrats in his district, he laments, "feel abandoned."

Here in this not even 10-minute interaction, I thought, was the nub of the Bustos report -- and the challenge it presents to party leaders who will be asked to grapple with its primary recommendation that Democrats focus on economic matters and steer clear of confrontation on contentious social issues. In theory, it seems obvious the party would do what it must to secure the loyalty of additional voters; in practice, though, this sort of overture means peace-making with people like Burns, through the face-to-face pragmatism of people like Goodin, some of whose views bump up inconveniently against the agendas of interest groups and the platform and mores of the party as a whole. Is Burns worth wooing back? And is Goodin a walking relic -- or a key cog in the future of the party? Either way, as Goodin argued in his introductory address to the legislature, this should not constitute grounds for disqualification as a Democrat. "I have fired a gun a time or two, and I am familiar with the Scriptures," he said. "Some might think that makes me an outcast in my own party. Nothing could be further from the truth. Our caucus is a caucus that values all points of view. There's enough space for a farm boy like me, as well as woolly liberals."

In a nutshell, this is the advice of Bustos' report: Widen the definition of Democrat.

"This is the face of what the party is going to have to accept if you want to be in the majority," Johnson told me.

"If we call ourselves a big tent party," Bustos said, "then we should act like it."

***

Goodin's Indiana District 66 went heavy for Trump. One reason: It used to have plenty of decent-paying, union-boosted jobs, anchored by the Morgan Packing plant. Now, there are far fewer, and paychecks for the ones that remain have gotten smaller. Two years ago, Goodin's hometown of Austin, population 4,200, was the epicenter of "the largest drug-fueled HIV outbreak to hit rural America in recent history," in the words of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Resulting mostly from the sharing of dirty needles to shoot painkillers, more than 200 people were infected -- a rate "comparable to some African nations," the CDC said. Louisville's Courier-Journal said Austin was at "the intersection of hopelessness and economic ruin." Now, as Goodin continued his drive from Austin to Scottsburg to deeper into his district, I looked out the window at what felt like stock footage of the rural Midwest-cornfields and cars in yards, above-ground pools and anti-abortion billboards, tired trailers and Dollar Generals.

"How many Delmises," I asked him, "do you suppose live in District 66, folks who wear MAGA hats and vote for you, too?"

Lots, he said.

Talking to Burns, and others like him, is "a great learning experience," Goodin told me. "You agree where you agree, and there's some things you may not agree on."

"Do you ever find yourself, as a Democrat, wanting to push back?" I asked.

"You're looking at a Democrat right there," Goodin said. "He's a Democrat who voted for Donald Trump."

"He's also," I said, "a Democrat who didn't want to train a Muslim in his truck because he was afraid of getting blown up."

"But you know," Goodin said, "you let people live their lives, and you don't question -- I mean, what good would it have done?" He went on: "There's no reason for confrontation -- that's the trouble with Congress now -- because Delmis Burns and I, you wash away some of the odd things, what some people may consider odd that he would have said, what he said about the Muslim guy -- the reason he said that is there's no Muslims around our area. So he just don't trust 'em. He don't know who they are. ... But Delmis Burns and I probably agree on 90 percent of everything we'd ever talk about. So why would I focus on the 10 percent that I don't agree with him on?"

When he was talking to Johnson for Bustos' report, Goodin told me, he thought about Burns. And the cost to the larger party of writing him off.

"Tell me how in the world Nancy Pelosi, or some of those folks in Congress," Goodin said, "how would they even be able to sit there and talk with Delmis Burns? Do they even know that a guy like Delmis Burns exists? That's why I say that the East Coast elitists have forgotten America. They've not been to America, they forgot America, they forgot about certain parts of America. Maybe they've done that intentionally. I hope they haven't."

Intentional or not, what's clear from the report is that many of these 72 rural Democratic lawmakers feel the national party is indifferent to the trouble it has caused them locally. And they're angry about it. Their assessments are blunt, searing -- and directed straight at Democrats on the coasts, in cities, in Washington.

"The Democratic Party is a party of elites," Michigan state Rep. Donna Lasinski told Johnson.

"Democratic leaders don't understand the needs of rural voters," former Illinois state Sen. John Sullivan said.

"The 'metro-centrics' in our party don't know the difference between majority and minority," Minnesota state Rep. Gene Pelowski added. "They just play to the base. They don't care about winning elections."

"The Democratic brand," said Illinois state Rep. Jerry Costello Jr., "is hugely damaged, and it's going to take a while to bring it back. Democrats in southern Illinois have been more identified by bathrooms" -- transgender bathrooms, that is -- "than by putting people back to work."

Several of the lawmakers who talked to Johnson called some in the Democratic Party intolerant.

"We say we're diverse and tolerant," former Indiana state Rep. Dennie Oxley said, "but we're really not tolerant of certain groups."

"Some in the party, especially from metro areas, are not tolerant of other opinions, especially on guns and abortion," Minnesota state Rep. Jeanne Poppe said. "It's OK, if you're liberal, to be intolerant."

Goodin agrees.

"Democrats have become less inclusive, the party has," he said to me one evening driving from Indianapolis back to Austin, snow-specked fields speeding by on either side of the car.

"The traditional Democrat Party was a party of diversity," Goodin said. Now? "They don't really walk the walk."

***

When I called Drew Hammill, Pelosi's deputy chief of staff, and told him about my trip to Indiana, and about the Bustos report, and about what Goodin had said, he didn't respond on the record directly to Goodin's comments. He did say he had been briefed about the report and embraced the overall advice to focus on pocketbook issues. "That's exactly what we're trying to do," Hammill said, mentioning the Democrats' new-ish "Better Deal" pitch. "If anything, this further buttresses the decisions that we as a caucus have made to emphasize jobs and the economy." Meanwhile, he disputed the notion that party leaders in Washington are to blame for losses in smaller races in the heartland. "If anyone in any state legislative race thinks they lost because of a congressional leader, that's just ridiculous," he told me. "That's just not how things work." Hammill reiterated: "The single most unifying factor for Democrats is our commitment to working people in this country."

That much he and Pelosi and Goodin agree on. Goodin is a Democrat in the first place, he told me, because his grandfather was a union coal miner in Harlan County, Kentucky, and because his father was the school superintendent in Austin. He's a staunch supporter of public education. A graduate of Eastern Kentucky University, he has a doctorate from Indiana University in Bloomington. But he calls himself a "Hoosier Democrat" the same way Senator Joe Manchin calls himself a "West Virginia Democrat" -- and that means, he said, that he takes some positions that are to the right of most of his fellow Democrats.

Gay marriage, too: In 2011, Goodin voted for a constitutional ban in Indiana; three years later, when public opinion had moved markedly and Democrats favored marriage equality, Goodin was excused from voting. When I asked him about where he stands now, he said he has "evolved" with his district. "They don't really care what people do in their private lives -- as long as they don't try to force their lives on me. Live and let live ..." He added: "I have to try to represent the majority of the district. And I think the majority of the people feel like it's nobody's business, it's the law now -- so you can't discriminate. And my personal opinion, whether I agree with it or not, doesn't matter."

Similarly, his posture on abortion is something party purists and even many standard-issue liberals see as inexcusably namby-pamby. Over the course of our time together, Goodin told me he considers abortion "a religious issue," something that "needs to be discussed in church." He said, "I'm pro-life. I'm not pro-abortion." He added, "I'm a Christian. At the end, I'm going to answer to one entity, and that's God." Politically, though, what does that mean? "Ultimately, the law of the land says that it's legal," he said. "I'm a pro-life Democrat who believes in individual rights and personal freedoms."

Back in late November, when Goodin became the leader of the Indiana House Democrats, Bustos called to congratulate him -- but his well-established rightward bent on hot-button social issues meant some of the more left-leaning members of his own caucus were not quite as pleased, according to Indiana Democratic sources. The 15-14 tally of the private vote, first reported by the Indianapolis Star, suggested as much.

I asked the chair of the Indiana Democratic Party if other Democrats were OK with Goodin being a leader. "If they're not," John Zody said, "they need to be OK with it. We are a big tent, and we need people who fit their districts."

Indiana-based rural strategist Melina Fox wishes the infighting would stop.

"He is a rural Democrat who's winning," she told me, "so maybe they need to be listening to him."

The lesson? "That the more moderate to conservative Democrat needs to come back in order for us to get the majority," said Baron Hill, the former Democratic congressman from southern Indiana who lost in 2010. "The Democrats have got to do a better job of appealing to what was described awhile back as the 'deplorables,' if you'll recall."

For Democrats to beat Republicans in areas like this in Indiana is "an uphill battle," said John R. Gregg, the centrist Democrat who ran for governor in 2012 and 2016 and lost to current Vice President Mike Pence and current Governor Eric Holcomb, respectively. "All they've gotta do in Indiana is just say the words Hillary Clinton, or liberal, or Barack Obama, or Democrat, and it gets people nervous. I've heard Terry remind them ... 'Hey, wait a minute, I'm a Democrat -- but I'm an Indiana Democrat.'"

"If we have a litmus test of who can be a Democrat and who shouldn't be, I think the Democrat Party would shrink pretty quickly," Goodin told me. "I think it's wrong. I think it's unproductive. And quite frankly, I think it smacks of elitism."

"We went into this project with an open mind and an invitation to the participants to speak their minds openly and honestly," the pro-choice Bustos said in the news release that announced the report. "While I don't agree with all of the comments we received, this report reconfirms my deeply held belief that Democrats must keep our eye on the ball by spending each and every day addressing the very real economic challenges facing families who are struggling and feel like Washington has left them behind."

"And when we have good Democrats," Bustos said, "either people who want to run for office, or are running for office, or are in office -- stop acting like they're, you know, not one of us, so to speak, because their views might be different."

"This is a guy the party is going to have to accept," Johnson said.

Why?

"He wins."

"The path to the majority," Bustos said, "is through the heartland."

Michael Kruse is a senior staff writer for Politico.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter