"We have to stop and take a deep breath and ask, 'What are we doing?' " said David Paulison, a former Miami-Dade County fire chief brought in to run the Federal Emergency Management Agency by President George W. Bush after the agency's response to Hurricane Katrina was harshly criticized. "The more people we put here, the worse it's going to be for evacuation."

Irma could have been Florida's worst nightmare: A massive Category 5 hurricane wide enough to hit both of the state's densely populated coasts, where growth has boomed despite the obvious risks of living on the water in an area regularly walloped by storms. The push for more development - one of Gov. Rick Scott's central policies in his successful effort to revive Florida's economy - is elevating the risks to both people and property, said Craig Fugate, FEMA chief under President Barack Obama and the state's emergency management director under Gov. Jeb Bush.

"We're trying to evacuate more people over the same infrastructure," Fugate said. "It's something Florida has to revisit."

Even though Florida was spared catastrophic damage, the evacuation - which experts say saved lives - felt like a disaster of its own to residents. Highways backed up for hours as people fled north. And state transit authorities were unwilling to change the direction of lanes because emergency vehicles and supplies needed to keep heading south toward the storm.

Valerie Preziosi and her husband, Jan Svejkovsky, left their home on Big Pine Key on Friday, along with their two cats. They booked a hotel room in Orlando but then changed course for Waldo, in north-central Florida, when the hotel didn't answer their calls. Then, as Irma wobbled, Waldo found itself at risk of flooding. Like many evacuees, they had fled from one danger zone to another. So they drove even further north to Macon, Georgia.

"We kept getting pushed up because the storm was pushing behind us," Preziosi said.

The worst was yet to come: Getting back from Macon to Orlando - normally a five-hour trip - ended up being a ride from hell.

"It was horrible, I mean horrible," she said. "We were in 14 hours of traffic bumper to bumper."

With gas stations locked and powerless, "there was no way to use a restroom," Preziosi said, "so there were people in the middle of highway traffic getting out of their car. There was an elderly woman being dragged out so she could have a bowel movement in the middle of the road. The whole thing was so surreal."

That's not to say the evacuation was ill-advised: Irma missed a devastating direct hit, but the storm still wiped out parts of the Florida Keys and Marco Island, flooded Jacksonville and briefly turned downtown Miami's major thoroughfares into white-capped rivers. Getting people out was the safest move, Gov. Scott said.

"My goal is keeping everybody alive," Scott said Wednesday at Homestead Air Reserve Base

If there is another major storm, "I'm going to do everything I can," the governor said, "to get everybody out of their homes and get everybody to shelter. ... It's an inconvenience to be displaced out of your home, it's an inconvenience to be without power, it's an inconvenience to try to find fuel, but the most important thing is survive."

Boom in the sun

By the basic measures of fatalities, Florida's evacuation - which saw 6.5 million people ordered to flee their homes - was a success. At least six people died in car crashes described as storm-related as of Thursday, including one in the Florida Keys. It's not yet clear if any of the dead were evacuees. Compare that to the catastrophe before Hurricane Rita in 2005: When Houston evacuated, desperate drivers created a deadly traffic jam. Dozens died, including 24 elderly people whose bus caught fire.

Florida's evacuation had problems, Paulison said, "but for the amount of people that moved, it went fairly well."

While roads were jammed, some of those who needed safety most were stranded. In Hollywood, eight nursing home residents died after the air conditioning in their facility failed, turning it into a sweltering death trap. They lived across the street from a hospital. Meanwhile, evacuation shelters across Miami-Dade County were understaffed. Schools chief Alberto Carvalho said Red Cross volunteers didn't show up in expected numbers.

South Florida's income inequality - the second-highest in the nation - exacerbated the problem as some low-income residents without cars or steady internet access didn't know where shelters were or how to get to them.

The bigger crisis will come as Florida keeps growing.

The state is built for bottleneck: If a storm sweeps up the peninsula from the south, the only way out is north. Florida has only three major north-south arteries: Florida's Turnpike and Interstate 95 on the east coast, and Interstate 75 on the west.

Both Paulison and Fugate said they support new development - if it's done smartly. But they cautioned the entire state might need to look to the Florida Keys for evacuation solutions. The Keys has limited its growth because of the potential for gridlock along the Overseas Highway, the island chain's only exit. And it conducts evacuations in stages, with tourists ordered out first and residents following.

Florida is now the fourth-fastest growing U.S. state. Big storms aren't scaring away new residents.

"The issue is not that we developed too fast, it's that we developed the wrong way," said Richard Florida, an urban planning expert at the University of Toronto and visiting fellow at Florida International University. "We have a gross over-dependence on the car and the single-family home that puts Florida at risk."

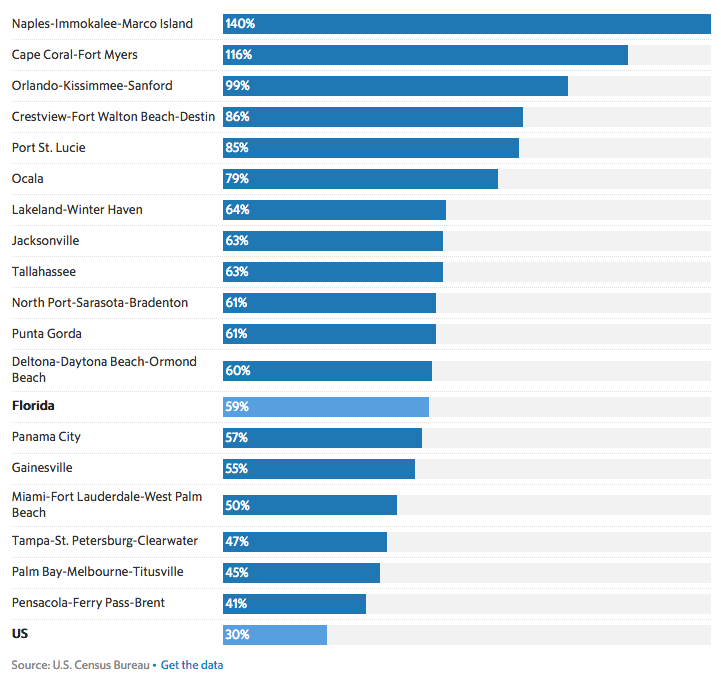

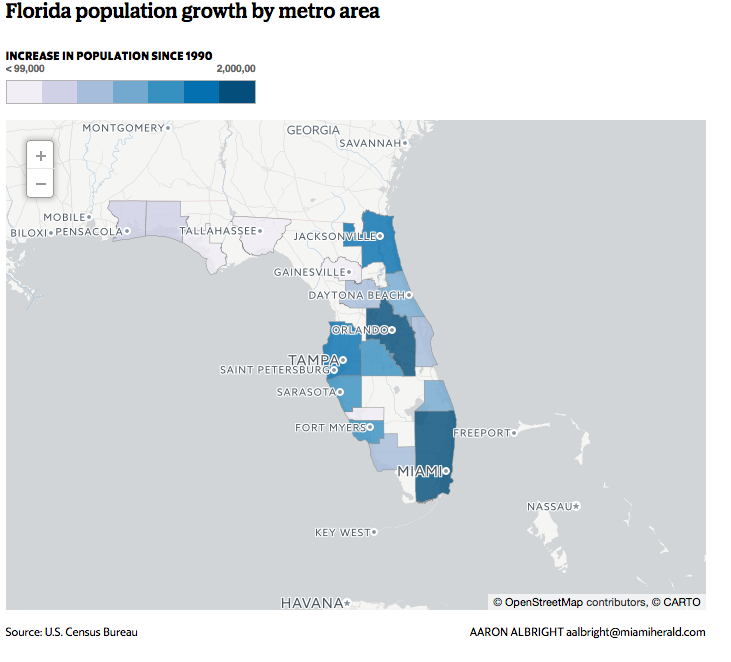

Since 1990, two years before Hurricane Andrew struck, the state added roughly eight million new residents, bringing its total population to nearly 21 million. That's a growth rate of 59 percent, almost double the national average. The state projects its population will surpass 25 million in less than two decades.

Much of the expansion has taken place south of Lake Okeechobee, in the state's most vulnerable, low-lying coastal areas. Armed with a sun-and-sand pitch, developers have turned a swamp into one of the nation's premiere destinations. Grateful cities - in a state without an income tax - depend on new development to boost their property tax revenues, giving them less of an incentive to weigh the feasibility of future evacuations.

Since 1990, the populations of the Naples and Fort Myers metro areas have more than doubled, according to U.S. Census figures. Miami and Tampa have grown 50 percent. Even areas without brand-name cachet are booming: The metro region around Port St. Lucie has grown 85 percent and, in greater Melbourne, the population is up 45 percent. Florida now has more people than New York.

And 91 percent of Floridians live in greater urban areas, Florida said. Only Washington, D.C.; New Jersey; Nevada; Massachusetts and Hawaii are more urbanized.

In South Florida, he said, "we're going to have to grow more like New York or London and less like a suburb," with an emphasis on high-speed rail and buses that can move people before a crisis. Proposals for that kind of public transit have been floated in Miami-Dade for years.

With airline ticket prices soaring with the storm looming, flying out wasn't an option for most.

While Florida's building boom created gridlock, it also helped the state recover quickly from a recession that hit like a Category 5 storm.

In 2011, Scott signed a bill scaling back the state's growth management law - passed in 1985 - and abolishing the agency responsible for ensuring that county building plans would not hinder evacuations. A development rush across the the state followed. But long-term safety risks remain.

"Everyone hates red tape," Fugate said. "But Irma's an example of what happens when you get rid of red tape and you just build."

McKinley Lewis, the governor's deputy communications director, issued the following statement: "Our office is 100 percent focused on keeping Floridians safe, and during emergencies, we work closely with county Emergency Management officials to accomplish that goal."

One area of Florida that has seen slow growth is the Florida Keys. The population of Monroe County has grown just 1 percent, to roughly 79,000, since 1990.

In the vulnerable Keys, residents are told to leave their homes starting at Category 1 storms. They are ordered out of the island chain altogether for Cat 3 storms and stronger. Tourists must leave before residents. New development is balanced against the need for timely evacuations and the Keys' ability to provide water and sewer services.

Before Irma, traffic out of the Keys was heavy but orderly. The problems started further north.

A costly flight

Knowing the disruption and economic losses an evacuation would cause, Miami-Dade Mayor Carlos Gimenez waited an extra day to judge the storm's path. But forecasts showed a potentially devastating impact. On Sept. 6, the order went out. Soon, a county website listing evacuation zones crashed - another sign of Florida's overloaded storm infrastructure - and a headlong flight toward safety began.

"Oh, my god, it was ridiculous," said Jessica Alexandre, who spent 22 hours on the road between Fort Lauderdale and her mom's house outside Atlanta Wednesday and Thursday. "That trip normally takes nine or 10 hours."

"We were just sitting for hours not even moving," continued Alexandre, who sometimes veered off onto dark, back roads to escape the crush on I-75. She prayed the car carrying her her aunt and her14-year-old rescue pug-mix, Primo, wouldn't break down.

"It was a free place to stay," Alexandre said of her decision to drive 660 miles. "I had a car and I had gas money. At that point, why stress myself out?"

She said she expected bad traffic but nothing like what she encountered.

Asked about the evacuations Tuesday, Gimenez said the ideal message to residents in future storms would be to "find a place near Miami-Dade County that you can evacuate to."

"Our plan is always to evacuate in place - to a friend's house, to family house, to a coworker - for those areas that we fear are threatened by storm surge," he said.

Condo madness

More than any other area of the disaster-prone state, South Florida has boomed from new construction. There are now 101 condo towers under construction east of I-95 in Miami-Dade, Broward and Palm Beach counties, according to Cranespotters.com.

The development market hasn't adjusted to the risks of hurricanes and sea-level rise, said Zac Taylor, a researcher at the University of Leeds who studies Florida's real estate market. One potential factor: Latin American investors - who may be less aware or less concerned by nature's threat - are driving the boom.

Foreign buyers purchased $6.2 billion worth of South Florida real estate between August 2015 and July 2016, 39 percent of the total dollar amount, according to the Miami Association of Realtors

"If you're buying a property to hold it for the short term, do you have a long-term interest in the place?" Taylor asked.

Irma might provide a wake-up call for a region that hasn't seen a major hurricane season since 2005. Some property owners are already looking to cash in.

One seller in Palm Beach Gardens is advertising a $1.25-million home with the tag-line "Don't be the first to evacuate again." The concrete home is equipped with two generators - and lies outside Palm Beach County's evacuation zones.

"It's further to the west from where the storms hit," said real estate agent Gene Arky. "It's a little fortress."

The 'news' that Florida became #3 in population of US States was per estimates in 2014, but .. we'll have to wait for official 2020 census to 'officially' confirm.)

It was beautiful here in the 60's . . . but still too damn hot. (And we didn't have A.C. in school, either. I don't know how the teachers took it.)

R.C.