Their efforts to warn the public may get an unlikely boost from the unprecedented disaster unfolding in Houston, where Tropical Storm Harvey dumped trillions of gallons of rain across Texas and brought America's fourth-largest city to its knees.

While epic flooding is different from a powerful temblor, both natural disasters fundamentally alter daily life for months or years.

In recent years, officials have drawn up detailed scenarios of what would happen if a huge quake struck this region, part of a larger campaign to better prepare.

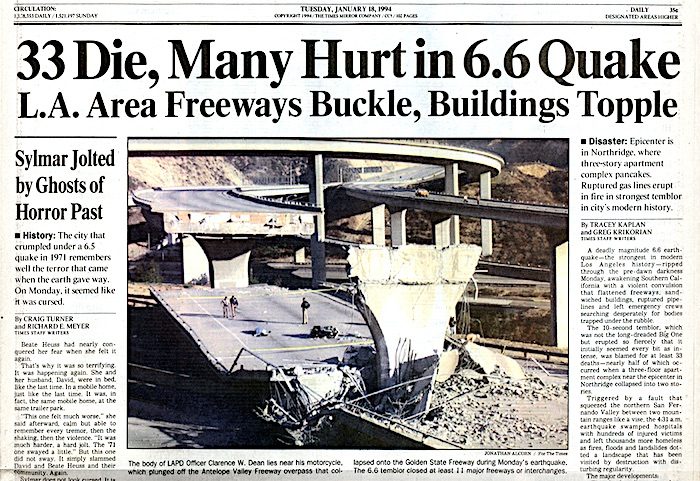

The last two big earthquakes to hit Los Angeles - the 1971 Sylmar quake and 1994 Northridge quake - caused destruction and loss of life. But the worst damage was concentrated in relatively small areas and did not fundamentally bring daily life across all of Southern California to a halt.

Experts have long warned that a significantly larger quake will eventually strike and that the toll will be far greater.

DANGER ON THE SAN ANDREAS

Preparing for a quake 45 times stronger than Northridge

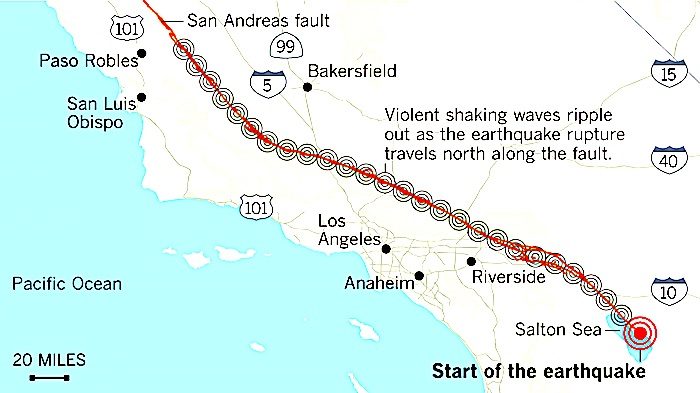

The biggest concern for scientists has been the San Andreas, because that fault has a long history of producing large earthquakes more often than others. The San Andreas is the longest and fastest-moving fault in California - a combination that makes it more capable of producing a catastrophic quake we might see in our lifetime.

A quake as strong as magnitude 8.2 is possible on the southern San Andreas fault and would bring disaster to all of Southern California simultaneously, with the fault rupturing between near the Mexican border to Monterey County.

Such an earthquake would "cause damage in every city" in Southern California, said seismologist Lucy Jones - from Palm Springs to San Luis Obispo and everything in between.

Back then, the region was sparsely populated. Today, some 23 million people live in eight counties in Southern California that could be hit hard in a southern San Andreas megaquake.

In 2008, the U.S. Geological Survey and a host of other state government agencies and academics published a study called the ShakeOut Scenario that told the story of what could happen if a hypothetical magnitude 7.8 earthquake returned to Southern California.

A 7.8 earthquake is a kind "so powerful that it causes widespread damage and consequently affects lives and livelihoods of all southern Californians. A catastrophe is a disaster that runs amok when a society is not prepared for the amount of disruption that occurs," the report said.

A GRIM SCENARIO

Hundreds dead, region paralyzed

Here are some of the findings of what could happen in a 7.8 earthquake that strikes at 10 a.m. on a dry, calm Thursday in November, based on feedback from 300 experts in both the private and public sectors:

The death toll could be one of the worst for a natural disaster in U.S. history: nearly 1,800, about the same number of deaths as resulted from Hurricane Katrina. More than 900 could die from fire; more than 400 from the collapse of vulnerable steel-frame buildings; more than 250 from other building damage; and more than 150 from transportation accidents, such as car crashes due to stoplights being out or broken bridges.

Los Angeles County could suffer the highest death toll, more than 1,000, followed by Orange County, with more than 350 dead; San Bernardino County, with more than 250 dead; and Riverside County, with more than 70 dead. Nearly 50,000 could be injured.

Main freeways to Las Vegas and Phoenix that cross the San Andreas fault would be destroyed in this scenario; Interstate 10 crosses the fault in a dozen spots and Interstate 15 would see the roadway sliced where it crosses the fault, with one part of the roadway shifted from the other by 15 feet, said Jones, who was the lead author of the ShakeOut report.

"Those freeways cross the fault, and when the fault moves, they will be destroyed, period," Jones said. "To be that earthquake, it has to move that fault, and it has to break those roads."

The aqueducts that bring in 88% of Los Angeles' water supply and cross the San Andreas fault all could be damaged or destroyed, Jones said.

A big threat to life would be collapsed buildings. As many as 900 unretrofitted brick buildings close to the fault could come tumbling down on occupants, pedestrians on sidewalks and even roads, crushing cars and buses in the middle of the street.

Fifty brittle concrete buildings housing 7,500 people could completely or partially collapse. Five high-rise steel buildings - of a type known to be seismically vulnerable - holding 5,000 people could completely collapse.

Some 500,000 to 1 million people could be displaced from their homes, Jones said.

EXPECT ISOLATION AFTER BIG ONE

Southern California cut off

Southern California could be isolated for some time, with the region surrounded by mountains and earthquake faults. The Cajon Pass - the gap between the San Gabriel and San Bernardino mountains through which Interstate 15 is built and is the main route to Las Vegas - is also home to the San Andreas fault and a potentially explosive mix of pipelines carrying gasoline and natural gas, and overhead electricity lines.

All it would take is for the fuel line to break and a spark to create an explosion. "The explosion results in a crater," the report says.

ShakeOut coauthor Keith Porter, research professor at University of Colorado Boulder, warned in a 2011 study in the journal Earthquake Spectra that under certain conditions, a magnitude 7.8 earthquake could create such a sudden interruption of high-voltage interstate transmission of electricity that "potentially all of the western U.S. could lose power."

Power could be restored within hours in other states, the scenario said. But restarting the electric grid in Southern California could take significantly more time.

Anne Gonzales, a spokeswoman for the California Independent System Operator, which runs the electric grid, declined to comment on the 2011 report, but said it could take several days to recover if a complete system blackout did occur.

"These are the kinds of things that keep me up at night," said Ken Hudnut, the U.S. Geological Survey's science adviser for risk reduction. Efforts are being made to work on vulnerabilities, such as the risk to the aqueduct systems, Hudnut said, including L.A.'s plan to strengthen the tunnel through which the Los Angeles Aqueduct crosses the San Andreas fault.

There could be up to 100,000 landslides, scientists say, based off how many landslides have occurred in past magnitude 7.8 earthquakes. "The really big earthquakes ... are much more destabilizing to the hillsides," Jones said.

Thousands could be forced to evacuate as fires spread across Southern California; 1,200 blazes could be too large to be controlled by a single fire engine company, and firefighting efforts will be hampered by traffic gridlock and a lack of water from broken pipes. Super-fires could destroy hundreds of city blocks filled with dense clusters of wood-frame homes and apartments.

The death toll could mount as hundreds of people trapped in collapsed buildings are unable to be rescued before flames burn through. Possible locations for the conflagrations include South Los Angeles, Riverside, Santa Ana and San Bernardino.

"If the earthquake happens in weather like today or in a Santa Ana condition, the fires are going to become much more catastrophic. If it happens during a real rainy time, we're going to have a lot more landslides," Jones said.

Several dams could be shaken so hard that "they would be so compromised that they would require emergency evacuation," Jones said. Even damage to just a single dam above San Bernardino could force 30,000 people out of their homes, the ShakeOut report said. Another problem, Jones said, could be shipment of key supplies, such as food, which are now distributed from areas like Victorville on the other side of the San Andreas fault as part of a "just-in-time" shipment economy.

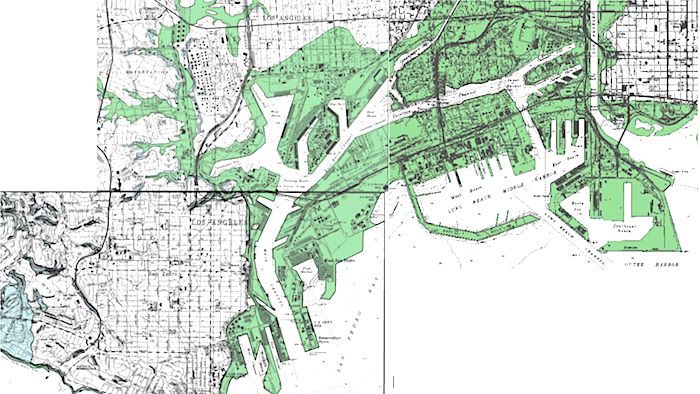

The USGS, FEMA, and the California Governor's Office of Emergency Services have also begun work on forecasting damage from other faults. Hudnut on Wednesday presented information based on a theoretical magnitude 7.3 quake on the Palos Verdes fault, which could rupture off the coast of Newport Beach and continue underneath the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach and into the northeast side of the Palos Verdes Peninsula.

Engineering options to reduce the liquefaction risk at the ports are costly and complicated. They include pumping water out of artificial land, injecting grout underground, or replacing concrete foundations that support buildings at the port, Hudnut said.

Trying to prepare for the worst

Some government agencies have been trying to focus on preparing for earthquake safety in recent years. The USGS and other agencies have led the ShakeOut earthquake drill annually for nearly a decade. A few California cities, such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, Berkeley, Santa Monica and West Hollywood, have enacted laws in recent years requiring retrofits of certain vulnerable building types, such as wooden apartments with flimsy ground-floor columns over carports that can collapse in an earthquake.

While interstates that cross the San Andreas fault will be severed in the ShakeOut scenario, other California freeways maintained by Caltrans are expected to perform well, given comprehensive retrofit work following the failure of elevated roadways in the 1989 Loma Prieta and 1994 Northridge earthquakes. And state officials subject hospitals and public schools to more stringent earthquake standards.

Many cities have yet to require vulnerable buildings to be retrofitted. But public sentiment is changing. In San Francisco, there was a time when the idea of the city requiring retrofits of apartments was controversial. Now, "people have kind of accepted it," said Patrick Otellini, the former director of earthquake safety for San Francisco.

The reality of Hurricane Katrina and Superstorm Sandy's toll on society have shown the proof of the great harm cataclysmic events can bring. Preparing for them, he said, is "something that has to be practiced all the time. Disasters are the new normal."

Comment: Heads-up, folks. We are heading into rocky times with potentially devastating events. For excellent research on this topic and its correlation to extended solar minimums and increased volcanism: Upheaval!, Why Catastrophic Earthquakes Will Soon Strike the United States, by author John L. Casey.