The teeth, retrieved from a cave named Lida Ajer, in the Padang Highlands on Sumatra's west coast, provide the earliest evidence of modern humans living in a rainforest - an environment known to be extremely challenging for incoming Homo sapiens, who were adapted to open grassland survival.

The research, published in the journal Nature, has ramifications in several areas.

Together with recent research indicating the earlier-than-expected arrival of modern humans in northern Laos, the study potentially resets the time frame for the arrival of Homo sapiens in Asia.

This, in turn, may cause a re-examination of timelines for modern human migration out of Africa. It could also impact on research establishing the earliest arrival of humans in Australia.

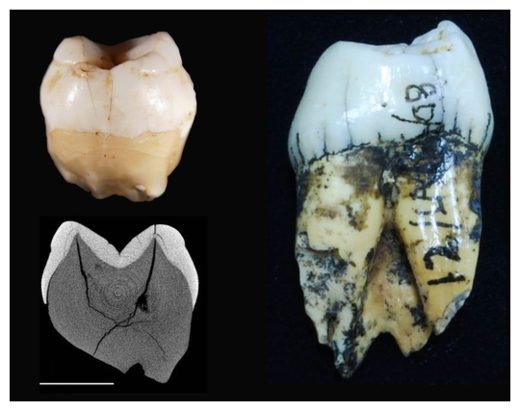

The teeth - an incisor and a molar - were actually discovered by Dutch paleoanthropologist and explorer Eugene Dubois in the late 19th century. Dubois classified them as hominin.

As a result, the Sumatran location has never featured in any serious exercise to map human inflow into Asia.

The teeth were re-examined 70 years ago by another Dutch paleontologist, Dirk Hooijer. He identified them as belonging to modern humans but was unable to provide a firm date for them. Evidence of other hominin species in the region - notably Homo erectus and Homo floresiensis - raised questions about the accuracy of his findings.

This prompted a team of scientists led by Kira Westaway of Macquarie University in Australia to travel to the fossil site to establish reliable dating evidence and to re-examine the teeth themselves.

"The hardest part was trying to find the site again," Westaway says. "We only had a sketch of the cave and a rough map from a copy of Dubois's original field notebook."

Eventually, however, Westaway and her colleagues were successful. Arriving at the site, they set about dating the deposit layer inside the cave in which the teeth were originally located, by using two different types of thermoluminescence analysis. Additional uranium-thorium dating provided supporting information.

Uranium-thorium dating was also used on fossilised gibbon teeth found in the deposit - some freshly found and one originally excavated by Dubois.

Next, the human teeth were subjected to a series of examinations, including enamel-dentine junction morphology, enamel thickness and comparative morphology.

The results confirmed Hooijer's findings, conclusively ruling out them coming from another member of the Homo genus.

Combining the dating results of the location and other fossils yielded a firm date range of the teeth being 63,000 to 73,000 years old.

Although claims for modern human settlement in Sumatra prior to 60,000 years ago had been made in the past, the evidence was indirect and considered open to question. Westaway's team has now provided definitive proof.

Even more interesting is that the proof comes from a site known to have been within a "closed-canopy" rainforest at the time.

Human migration into previously uninhabited areas is thought to have occurred mainly along coastal routes, because open marine-linked environments provided the easiest and most food-abundant access.

"Conversely," write the researchers, "rainforests, with their highly spaced, seasonal resources, scarce fat-rich faunas and dearth of carbohydrate-rich plants, present serious difficulties for movement and colonisation by hominins that evolved in open environments.

"Successful exploitation of rainforest environments requires the capacity for complex planning and technological innovations: the behavioural hallmark of our species."

The Lida Ajer fossils, they go on to say, indicate incursions from coastal to forest environments happened much earlier than previously thought, possibly very close to the time of first arrival.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter