Mr. Al-Hassan, a 28-year-old Syrian, says he started to trade antiquities in 2015 after being contacted by a top official of Islamic State who sought his archaeological expertise to find Western buyers.

Later, he became a cog in an international supply chain smuggling art looted by ISIS.

ISIS's territorial grip is fading fast: Iraq has declared victory over the terrorist group in Mosul and ISIS is fighting to hold its self-proclaimed Syrian capital Raqqa - the last major city under its control. But the group's legacy of looting will linger for many years, law-enforcement officials say, in much the same way that art looted by the Nazis continues to surface 70 years later. The ancient statues, jewelry and artifacts that ISIS has stolen in Syria and Iraq, are already moving underground and may not surface for decades, according to these officials and experts in the trade.

"Once looted in Syria and Iraq, objects enter a gray market shrouded in secrecy," said Michael Danti, an archaeologist who directs the Boston-based Cultural Heritage Initiatives and advises the U.S. State Department on the looting of antiquities in Syria. "It's a problem that will stay with us for years to come."

Western security officials say they expect revenue from looted antiquities from Iraq and Syria to become an increasingly important source of money for ISIS if its other revenue streams, such as oil, continue to dwindle.

"ISIS is increasing pressure on this line of trafficking to compensate for the loss of petroleum revenue," a French security official said.

While it's impossible to know how much money these stolen artifacts provide to ISIS annually - estimates range from the low tens of millions by Mr. Danti to $100 million by another French security official - the income is considered noteworthy.

The Wall Street Journal interviewed Syrian art traders, recent ISIS defectors who worked in antiquities, and law-enforcement officials in the U.S., France, Switzerland, and Bulgaria to piece together how the international antiquities smuggling operation works.

Their accounts describe a pattern of trafficking in which ancient objects make their way from archaeological sites in Iraq and Syria, across borders with Turkey and Lebanon, to warehouses in Europe and Asia to await sale to dealers in the West.

Last month, Oklahoma City-based arts-and-crafts retailer Hobby Lobby settled claims with the U.S. government by paying a $3 million fine and surrendering artifacts believed stolen in 2010 and smuggled from Iraq. In response to the claims, which are related to allegations of trading items looted prior to the emergence of ISIS, Hobby Lobby said it would surrender the artifacts, pay the fine and adopt new procedures for buying cultural property.

ISIS hasn't commented on the trade in antiquities.

Mr. Al-Hassan and another Syrian art trader, Omar Al-Jumaa, said they agreed to speak to the Journal in person to denounce ISIS and draw attention to the group's role in the antiquities trade.

Like others involved in antiquities smuggling, Mr. Al-Hassan trades under an alias. He identified himself by his trading name, Mohamed Al Ali, in an interview for a May 2017 Wall Street Journal video about looted art.

In more recent interviews, Mr. Al-Hassan declined to say whether he is currently active in the trade. Mr. Al-Jumaa said he is currently selling looted objects.

Before the civil war, Mr. Al-Hassan said he was an English-language student who had begun studying archaeology in his spare time, inspired by a friend's father. His knowledge in that field became an asset when the rebel Free Syrian Army took control of his region of Eastern Syria in 2013 and he began regularly digging antiquities for the group.

When the territory passed into the hands of Islamic State in June 2014, Mr. Al-Hassan said he and other young men were arrested by the terror group and accused of collaborating with the FSA. Mr. Al-Hassan said he and four other men, including his neighbor, were blindfolded by a Tunisian ISIS commander and lined up in a school. Everyone in the group, except for Mr. Al-Hassan, was shot in the head, he said. Mr. Al-Hassan says he was spared when ISIS officials told him they had no proof of his connection with the FSA.

One year later, he says, he was contacted by Abu Laith Al-Dairi, the ISIS official in charge of antiquities, to sell artifacts looted by the group. "We have a lot of objects," Mr. Al-Hassan remembers Mr. Laith Al-Dairi saying over the phone. "I need you to find European buyers."

For many Syrian traders and smugglers, antiquities are one of the few ways they can earn a living. "They are destroying our history," said Mr. Al-Hassan. But "traffickers love them because they can make money."

The Journal couldn't verify some details of Messrs. Al-Hassan and Al-Jumaa's stories about their lives in Syria. But their accounts of the antiquities trade squared broadly with those of law-enforcement officials. Mr. Al-Hassan, for instance, told the Journal last year about a Roman-era ring that ISIS's Mr. Al-Dairi was trying to sell. Later, in December, the U.S. Justice Department filed a civil complaint seeking the recovery of that object and other Syrian-looted artifacts from the group and named Mr. Al-Dairi as a key figure in the trade.

Islamic State seizes antiquities from Syria and Iraq by giving licenses to locals to dig for them, according to people involved in the trade. The digging operation is often overseen by the group's cadre of foreign jihadists, which the organization considers more loyal than locals.

Initially, ISIS didn't charge for the licenses but demanded loyalty from diggers and 20% of the estimated value of each object they excavated, these people say. Now, however, ISIS demands that diggers sell all discovered items to the group at a 20% discount of their estimated market value; ISIS then resells the objects itself, according to Mr. Al-Hassan. As ISIS loses territory, such rules are applied unevenly depending on the local leader, Mr. Danti said.

The illegal trade is "not just for funding the [terrorist] group itself, but for creating ways to bring funds to its subjected population, whose hearts and minds Islamic State is trying to win," Yaya Fanusie, director of the Washington-based counterterrorism think tank Foundation for Defense of Democracies, told a U.S. congressional hearing last year.

A network of independent intermediaries buy artifacts from ISIS and carries them out of Syria and Iraq, often blending in with humanitarian convoys and refugees, Western officials and ISIS antiquity traders say. They are also hidden in exports such as cotton, fruit and vegetables.

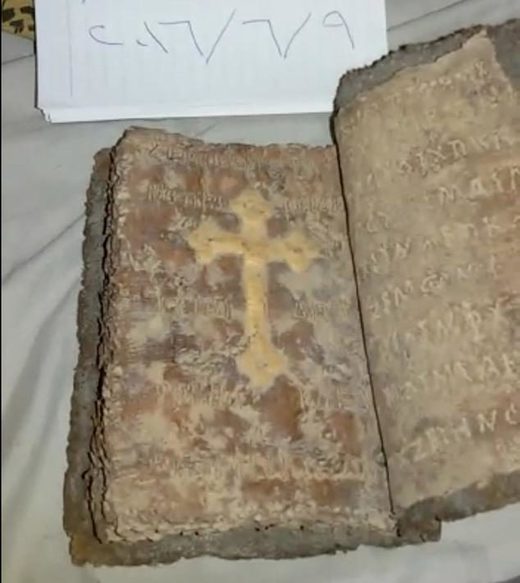

Mr. Al-Hassan said he recently sold two antique bibles looted by Islamic State from a site in Eastern Syria to a Russian buyer in a city in Southern Turkey for €10,000 ($11,800). The Russian then smuggled the bibles out of Turkey, hidden in a truck with vegetables, he said. Mr. Al-Hassan said he kept a commission of 25% and gave the rest to the trader who had brought the object to Turkey.

Other smugglers employ different ways to hide their cargo.

Mr. Al-Jumaa, said he paid $1,000 to a local Syrian woman wearing a long black robe known as an abaya to carry a bronze Roman statue across the Turkish border from Syria in her bag. The statue, of a warrior with winged helmet and a shield, had originally come from Raqqa, he said. The Turkish border police rarely check on women for religious reasons, Mr. Al-Jumaa said.

Mr. Al-Jumaa said he picked up the statue from the woman on the Turkish side of the border and drove it to a city in Turkey, where he said he is currently looking for a buyer. (Mr. Al-Jumaa said he later discovered that the object may be a reproduction made in the 1920s.)

Like Mr. Al-Hassan, Mr. Al-Jumaa has reason to hate Islamic State. He said he was jailed in 2014 after assaulting a member of the group who had refused to let him take a cousin badly burned in an air attack by the Syrian regime to Damascus for treatment. Every morning, an Islamic State jail warden put a large kitchen knife to his throat and said the group would execute him that day.

But after escaping to Turkey he said he began trading for the group. "I don't feel happy selling our history, but I need the money," said Mr. Al-Jumaa, who was a law student when the war broke out.

Despite ISIS's territorial losses, the trader says his business is doing well because so many items plundered by the group are now in circulation. Last week, he said he was set to meet four Lebanese men he had communicated with over WhatsApp who were traveling to Turkey to buy a cut emerald he said was looted by the organization in Mosul in 2014. Mr. Al-Jumaa is asking $600,000 for the precious stone, he said, but negotiations with a British trader to sell for that amount failed in March.

Mr. Al-Hassan said an Iraqi-Kurdish trader on July 30 was trying to sell a 3rd-century Palmyrene limestone statue of a woman after bringing it to Istanbul. On Aug. 1, traders on the Syrian side of the border were offering an ancient Greek silver pendant and antique Hebrew coins looted in Western Syria, as they tried to smuggle them into Turkey, Mr. Al-Hassan said.

In the majority of cases, artifacts from Iraq and Syria are first smuggled into Turkey or Lebanon, European and U.S. officials say, calling those countries key smuggling hubs. From there they often pass through southeastern European countries like Bulgaria and Romania and then into Western Europe, in particular Germany and Switzerland, according to the officials.

Bulgarian police once searched a shipment of clothes from an undisclosed location and found ancient coins disguised as buttons on jackets, according to a December report written by the Organized Crime Unit of Bulgaria's Interior Ministry and seen by the Journal.

Increasingly, objects are being shipped to Southeast Asian nations, like Singapore and Thailand, before making their way back to Western Europe, Brian Daniels, a research associate at the Smithsonian Institution told the House Financial Services Committee at a hearing in June.

That's because Asian markets are less closely monitored by customs officials, European officials say. If the objects arrive in the West from Asia, that may help cover their Middle-Eastern origin as they cross borders, Western security officials say.

In March 2016, police in Paris seized stolen steles from a marble altar as it transited from Lebanon to Thailand. The artifact originated in the middle area of the Euphrates Valley, which spans Syria and Iraq and was largely controlled by ISIS at the time, French customs officials said. It was being shipped via Asia to help mask a suspected final destination in the U.S., according to French security officials familiar with the matter. French authorities tracked the sender to an address in North Lebanon but are still trying to find that person's identity, they say.

Once a smuggled artifact lands with an art dealer in Europe or the U.S., the journey is still not over. To "launder" their origin, smuggled artifacts can be stored in warehouses for years and an ownership history is fabricated, according to a French security official and the Bulgarian report.

In the June House Committee hearing, Mr. Daniels said that it could take six to nine years for the art now being smuggled to hit public sale. A U.S. security official involved in investigations into art trafficking said it could take over 10 years in some cases.

Traffickers often use old typewriters to backdate certificates of ownership, another French official said. Objects are also moved from dealer to dealer to create a fake paper trail that makes their ownership harder to prosecute, said Mr. Danti, the director at the Cultural Heritage Initiatives.

There are around 20 major art galleries and trading houses in Western European cities that offer smuggled artifacts, the Bulgarian report said, without naming them. "The trade's main target buyers are, ironically, history enthusiasts and art aficionados in the United States and Europe - representatives of the societies which ISIS has pledged to destroy," Mr. Fanusie told Congress last April.

The FBI has a $5 million reward for any information about looted materials coming into the U.S. from Syria and Iraq. No one has come forward to claim a reward, law-enforcement officials say.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter