The findings included the remains of a unique grapevine honey produced by traveling beekeepers along rivers, according to a new study.

"The importance of beekeeping in the ancient world is well known through an abundance of iconographic, literary, archaeometric and ethnographic [or cultural] sources," Lorenzo Castellano, a graduate student at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at New York University and first author of the new study, told Live Science. (In archaeometry, scientists use physical, chemical and mathematical analyses to study archaeological sites.)

Even so, since honeycombs are perishable, direct fossil evidence of them is "extremely rare," he added.

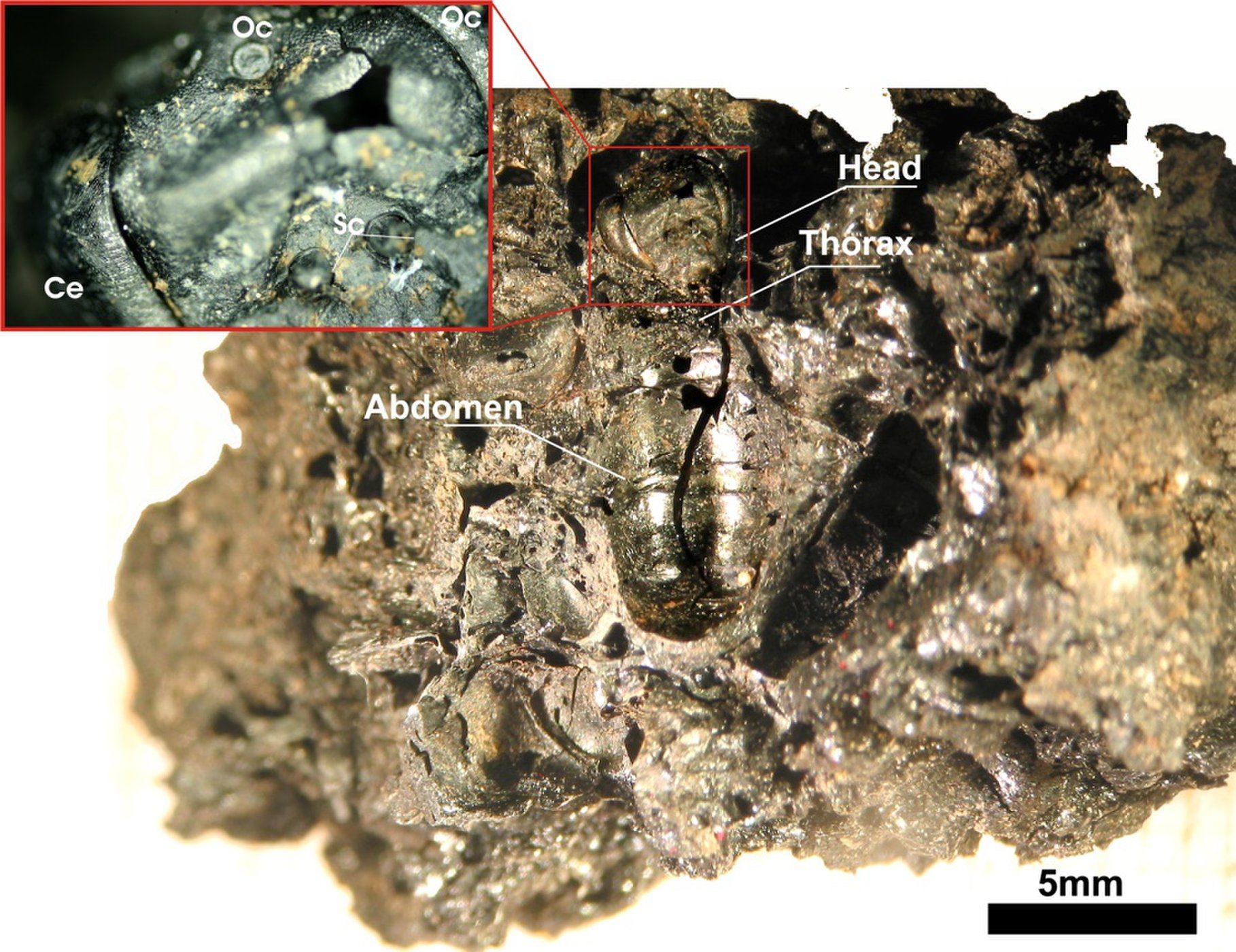

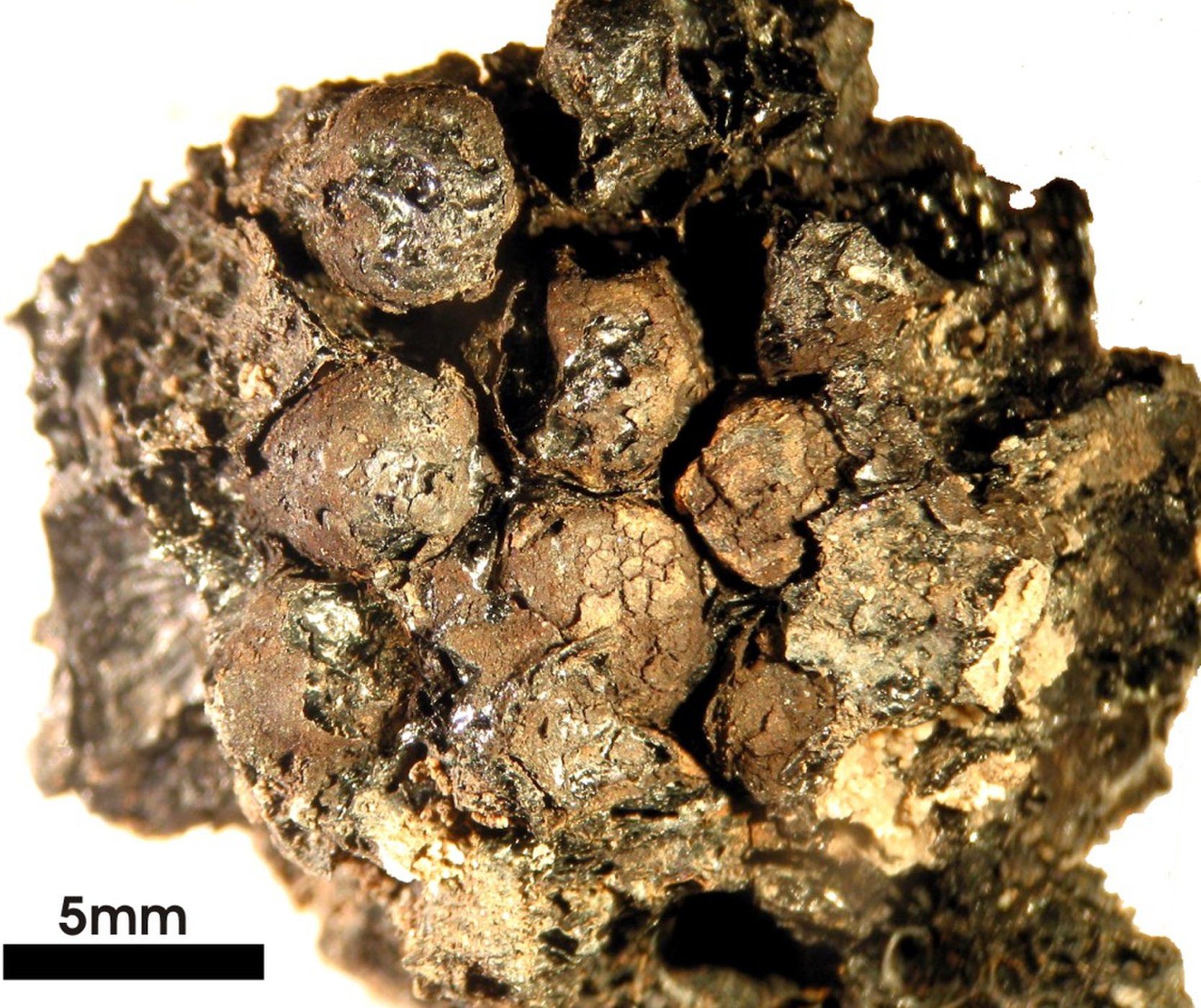

Castellano and his colleagues at the University of Milan and the Laboratory of Palynology and Paleoecology of the Institute for the Dynamics of Environmental Processes at Italy's National Research Council (CNR-IDPA) in Milan found several charred honeycombs, preserved honeybees and honeybee products scattered on the floor of a workshop at the Etruscan trade center of the ancient site of Forcello, near Bagnolo San Vito in the Mantua province.

"The findings are therefore preserved in situ, albeit heavily fragmented and often warped by the heat of fire," Castellano and his team wrote in July in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

The researchers examined bee-breads (a mixture of pollen and honey), fragments of charred honeycombs, remains of Apis mellifera (honeybees) and a large amount of material resulting from honeycombs that had melted and clumped together.

Chemical analysis and an examination of pollen and spores collected at the site confirmed the presence of beeswax and honey on a large portion of the room. Moreover, they found that pollen from a grapevine (Vitis vinifera) abounded in samples from the melted honey and in the honeycomb fragments, indicating the presence of a unique grapevine honey produced from predomesticated or early-domesticated varieties of grapevine.

Today, grapevine honey really has nothing to do with bee-produced honey; it is a kind of syrup produced by boiling grape juice.

The analyses revealed other unique aspects about the Etruscan beekeeping.

Pollen composition showed that honeybees were feeding on plants, including grapevines and fringed water lily, from an aquatic landscape, some of which weren't known to grow in the area.

Such a scenario would have been possible beekeepers who collected bees along a river while aboard a boat, bringing the bees and their hives to workshops to extract the honey and beeswax.

Indeed, the finding confirms what Roman scholar Pliny the Elder wrote more than four centuries later about the town of Ostiglia, some 20 miles (32 kilometers) from the site. According to Pliny, the Ostiglia villagers simply placed the hives on boats and carried them 5 miles (8 km) upstream at night.

"At dawn, the bees come out and feed, returning every day to the boats, which change their position until, when they have sunk low in the water under the mere weight, it is understood that the hives are full, and then they are taken back and the honey is extracted," Pliny wrote.

The finding also shows the Etruscans' high level of specialization in beekeeping.

"It also provides unique information on the ancient Po Plain environment [a geographical feature in northern Italy] and on honeybees' behavior in a pre-modern landscape," Castellano and colleagues concluded.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter