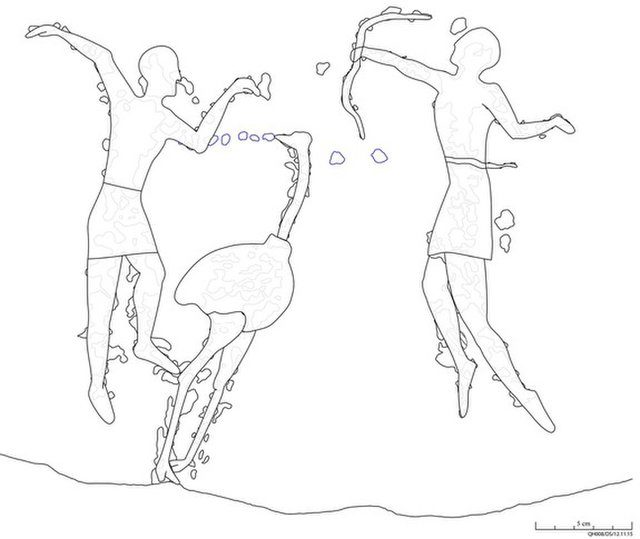

A drawing showing the Neolithic rock carving from Qubbet el-Hawa in greater clarity. Mask use was previously unknown from this era of pre-dynastic ancient Egypt.

The image, discovered recently by archaeologists, provides a tantalizing glimpse of Egypt's Neolithic period, or Stone Age. It likely dates back to the latter half of the fourth millennium B.C., said Ludwig Morenz, an Egyptologist at the University of Bonn in Germany. The depiction of a masked dancer in this era is particularly fascinating, Morenz told Live Science.

"[In] ancient Egyptian culture, we know many, many masks, but they are basically all masks for the dead," Morenz said. "And here we have a mask culture which predates pharaonic culture."

An ancient necropolis

The ancient find sits on Qubbet el-Hawa, the Hill of the Wind, near Aswan. In the pharaonic era, this was near the southern border of Egypt, and it was the site of a necropolis for the nobles of the ancient city of Elephantine, which was on the island of Elephantine in the Nile.

The necropolis was used from about 2200 B.C. onward, Morenz said, and it likely had nothing to do with the Neolithic use of the site; rather, this stretch of the Nile likely appealed to both Stone Age and later people because it is a relatively shallow stretch of rapids, called a cataract, with an island and easy pullouts for boaters.

"What I think is quite likely is that these rock images were placed on ancient pathways which have nothing to do with the later pharaonic necropolis, but where there was communicative access for whatever reason," Morenz said.

Long history

The images are barely visible in the rock today, but their discovery required no excavation — or, in Morenz's words, it was still "archaeology for lazy people." The team discovered the carved rock simply by surveying the landscape around the Qubbet el-Hawa necropolis.

The carving shows a hunter with a bow next to an ostrich. By the ostrich is a person wearing an ostrich mask. This person might have been a shaman, and the mask might have had ritual purposes, Morenz said. Archaeologists aren't yet sure what the belief system behind these rituals might have been, but there are examples of other Near East Neolithic cultures that used masked dancers, he said.

"Similarity does not necessarily mean there was a direct contact, and it does not even necessarily mean that there was an influence," Morenz said. "Sometimes things may be similar due to similar conditions."

However, there may well have been contact between the Neolithic people of Egypt and their neighbors in the fertile crescent of Mesopotamia, Anatolia and Elam, where other examples of ancient masks have been found, Morenz said.

Whatever their purpose, masks for the living dropped out of tradition by the time the pharaohs united Egypt around 3100 B.C. For now, Morenz said, the carving opens up new questions into this mysterious era of Egyptian history while also lengthening the history of Qubbet el-Hawa.

"This archaeological area is about a millennium older than we knew before," Morenz said.

This finding was recently honored as one of the current most important discoveries in Egyptology by Egyptian Minister of Antiquities Khaled El-Enany.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter