Yet most of us know that perpetual joy is not a practical goal—and recent research is starting to suggest that it may actually be a harmful one. Scientists are discovering that feel-good states can be detrimental to our problem-solving, judgment, morality, and empathy in the moment.

The upshot? Context matters.

On the whole, it's absolutely beneficial to be someone for whom feeling good comes easy, who can appreciate a good meal, connect warmly with others, and dream up sunny possibilities for the future. But our whole spectrum of different feelings, from anger to elation, evolved for a reason: to help us confront and handle challenges to survival. There are times in life when feeling positive won't help—and could even hurt.

1. When you're working on critical reasoning tasks

Research suggests that positive feelings can help us be more productive at work overall and more adept at creative tasks, particularly those that involve brainstorming responses and ideas. But a positive mood isn't conducive to the best performance on certain analytical tasks.

In a 1989 study, researchers induced a positive mood in half the participants by either giving them $2 or showing them a funny video. Then, everyone read an editorial they disagreed with—except some editorials contained strong, thoughtful arguments, and others contained weak arguments.

Under time pressure, the amused participants were equally persuaded by the strong and weak arguments, couldn't remember as many of the points made, and relied on shortcuts more in their evaluations (whether the author was a scholar or not) compared to the control, non-amused group. (When amused participants had more time, these patterns disappeared: They read for longer, and then they were more likely to be persuaded by strong arguments, remembered more details, and didn't tend to rely on shortcuts.)

In a 1995 study, a group of around 60 undergrads solved syllogisms—logic problems that ask you to deduce conclusions from statements like "All A are B" and "Some B are C." Again, a group that had been induced to feel amused performed worse. They spent less time working on the syllogisms and drew fewer diagrams to help solve them. They also gave riskier "all" or "none" answers (rather than "some"), perhaps indicating that they were overoptimistic about their problem-solving abilities.

The authors of a different study from 1994 offered this interpretation:

A 2000 study complicates the picture a bit, though. Here, students read moral dilemmas and had to pick the best arguments to solve them; their performance was rated more highly if they chose arguments that were more principled and abstract, rather than concrete and simple. In this situation, amused people took longer and performed worse. But this wasn't always the case: When students imagined themselves in the moral dilemma, or when the moral dilemma was serious and disturbing, involving war or racism, the amused students performed just as well as those in a neutral mood."Happiness is a kind of safety signal, indicating that there is no current need for problem solving....Unhappy people will think more deeply about their social environment (in an effort to solve their problems), whereas happy people can contentedly coast on cruise control, not bothering to think very deeply about surrounding events unless they impinge directly on their well-being."

In the end, the type and even the content of the task we're working on matter. For some parts of the work we do, particularly tasks that involve logical reasoning and critical thinking, positive emotions may not be the best helper. In other words, don't expect yourself to feel joyful proofreading a document or formatting a spreadsheet; serious focus may not be pleasant, but it may be the optimal mood for certain tasks.

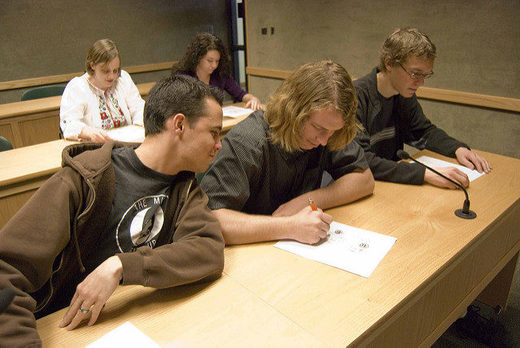

2. When you want to judge people fairly and accurately

Cognitive psychologists classify stereotyping as a form of "heuristic processing": using general knowledge about a group to efficiently make predictions about individual members. In this sense, stereotyping is a kind of superficial thinking—and people in a good mood may be prone to it.

In a 1994 study, participants were asked to make judgments about student misconduct; some had been induced to feel good by remembering and writing about a happy event from their past. The researchers were trying to find out if participants feeling good would make more stereotyped judgments: judging the Latino student guilty of assault or the track-and-field athlete guilty of cheating.

And so they did. (Notably, researchers were able to overcome this bias by telling happy participants that they would be held accountable for their judgments and should be able to justify them—effectively increasing their motivation to make good judgments with external accountability, and eliminating stereotypical reasoning in the process.)

People feeling amused also made more stereotypical judgments in a 2000 study: Here, they were more likely to (incorrectly) identify African-American-sounding names as belonging to criminals or basketball players. They didn't make the same mistakes with European-sounding names. Participants in a neutral mood weren't as likely to fall back on stereotypes.

However, other research has shown that white people in a happy mood show less implicit bias toward African-American faces—so, again, the effects may be complex. Perhaps it matters whether we come face to face with the people we're judging, where a happy mood may help dampen our fear response to unfamiliar faces.

In any case, it's still true that people who are in a good mood are sometimes more likely to jump to conclusions about others—and less likely to consciously correct for any stereotypical notions they harbor.

3. When you might get taken advantage of

The 2000 study also found that feel-good participants were prone to applying European-American names to politicians—a (theoretically) positive bias.

If feeling good inclines us to see certain people in a positive light, does that mean it might make us more likely to be manipulated? Maybe.

In a 2008 study, nearly 120 students were induced to feel amused, neutral, or sad (by watching a comedy video, a nature documentary, or a film clip about cancer). Then, they watched interrogation videos where other students lied or told the truth about stealing a movie ticket. Overall, the negative-mood group was better at detecting deception than the neutral or positive groups, correctly identifying the liars more often.

Researchers believe this is because a negative mood makes us process information in more detailed, systematic ways, and also makes us more likely to recall other negative information (like when our roommate lied about stealing our Pringles).

People intuitively seem to realize this: When we express high levels of happiness, research suggests, we are perceived as more naive and are more likely to be targets of exploitation than when we express moderate happiness. This explains why we wait for people to be in a good mood before we ask for favors, hoping that they won't be as critical and careful in considering our request.

4. When there's temptation to cheat

In some cases, feeling good may also compromise our morality.

In a 2013 study, 90 students were induced to either feel positive or neutral by watching clips from a cartoon or something resembling a screensaver. Then, they were instructed to complete a crossword-puzzle-type task, grade their own work with an answer sheet, and compensate themselves 50 cents for each correct answer. Although the worksheets appeared to be anonymous, invisible ink let the researchers figure out who was honest and who wasn't—and the amused group stole more money than the neutral one.

In surveys, the amused group reported being more morally disengaged—more apt to come up with justifications for immoral actions without judging themselves harshly. In this case, for example, they might think, "I'm not getting paid enough for this boring experiment, and I could have found more words if I tried harder."

Interestingly, these effects disappeared when the researchers put mirrors in their workspace, making them more self-aware.

"Although conventional wisdom would suggest that happy people are less likely than unhappy people to be dishonest, our work suggests that anyone who buys into this simplistic cliché might be blindsided by the stealth behind the smile," the researchers write.

5. When you're empathizing with suffering

Research suggests that being happier in general makes us kinder and more generous. But people who try to feel good all the time, at all costs, can miss some opportunities to connect with others.

A 2014 study, for example, found that positive people less accurately empathize with certain negative emotions. Over 120 young adults watched four videos, where people described good or bad events in their own lives (e.g., winning a scholarship or having a dispute with a landlord). During the videos, the participants continuously rated how they believed the storyteller was feeling on a scale of one to nine, changing their rating any moment they sensed an emotional shift. Those ratings were compared to the storytellers' ratings of their own feelings over the course of the video.

In general, positive participants—those who reported experiencing positive emotions more in general—were more confident in their empathic skills but weren't actually any better at identifying the storytellers' emotions than other participants.

In fact, when the storyteller was describing a high-intensity negative event, like the death of a parent, positive people were less accurate than their peers. For whatever reason, they seemed unable or unwilling to engage with such difficult emotions.

"It perhaps takes more sacrifice to 'drop down' and focus on another person's high-intensity negative emotions, and this may be particularly difficult to do" for positive people, the researchers explain.

If there's anyone in your life with inveterate positivity, you've probably experienced something similar. When I share my anxiety or sadness with a hyper-positive friend of mine, he usually insists that the situation doesn't merit despair, or reassures me that everything will turn out okay—neither of which make me feel better (or understood).

Should we give up on feeling good?

Clearly, while feeling good does feel good, it doesn't always bring us the success and connection we desire. It doesn't seem ideal in all situations for all outcomes, meaning—as evolutionary psychologists could have already told us—that other, less-blissful feelings serve a purpose.

Indeed, according to a survey of more than 35,000 people, those who reported high levels of positive emotion weren't as protected against depression as those with high emodiversity—who experienced many positive and negative emotions, from awe and amusement to anger and sadness.

And that's another point worth making: "Feeling good" doesn't always refer to the same feeling. Much of the research focused on amusement, induced by watching a cartoon or a standup comedian. And none of the studies looked at warmer, more interpersonal feelings like love and compassion.

In a quest for more happiness, I once tracked my mood every hour for a month, hoping to identify the downers in my life and try to eliminate them. But instead, I came away from that experiment a little less concerned about my negative moods—because they never lasted! Each hour brought a new feeling with a different cause, and I realized I didn't have to stress so much.

Similarly, this research might help you relax about yesterday's bad mood—and give you a greater appreciation for all sorts of feelings.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter