Researchers at the Université de Montréal, Arizona State University and the University of Genoa analyzed 29 beach pebble fragments recovered in the Caverna delle Arene Candide complex on the Mediterranean Sea in Liguria, Italy. The site is a necropolis containing the remains of some 20 adults and children from the Upper Paleolithic period.

The cave was first excavated in the 1940s and is located about 90 meters above sea level on the upper margin of the former Ghigliazza quarry. The cave has great archaeological importance because it is a reference site for the Neolithic and Paleolithic periods in the western Mediterranean.

What is particularly interesting about the study is that occasionally, pieces of rock or pebbles uncovered during an excavation go unstudied, simply being regarded as artifacts of no consequence.

In this study, by closely examining the stone pieces that were found microscopically, as well as by conducting other tests, it was discovered that a funeral ritual was carried out some 5,000 years earlier by humans than previously thought.

The Palaeolithic, or Stone Age, is the longest period of human history. The Upper Paleolithic Period began about 40,000 years ago and can be identified by the emergence of regional stone tool industries and is associated with the modern Cro-Magnons. Keep in mind that during this period, complexities and specialization in stone tools were a step up from early stone age tools.

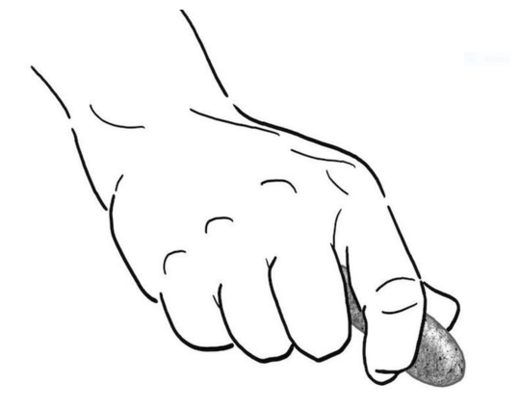

When someone died, family members and others in a group would go down to the beach and gather oblong stones to be used for a specific purpose. In other words, only stones of a specific shape and size were used. These stone "spatulas" were then used to apply red ochre to the body of the deceased.

The researchers determined the stones were then broken and discarded. Breakage appeared to have been intentional with many of the pebbles being broken by direct blows to their center.

The study's co-author Julien Riel-Salvatore, an associate professor of anthropology at UdeM said the intent could have been to "kill" the tools - "discharging them of their symbolic power" after they had come into contact with the deceased.

The study's lead author Claudine Gravel-Miguel, a Ph.D. candidate at Arizona State's School of Human Evolution and Social Change, in Tempe, said, "If our interpretation is correct, we've pushed back the earliest evidence of intentional fragmentation of objects in a ritual context by up to 5,000 years."

"The next oldest evidence dates to the Neolithic period in Central Europe, about 8,000 years ago. Our analysis puts the date to somewhere between 11,000 and 13,000 years ago when people in Liguria were still hunter-gatherers," Gravel-Miguel added.

An emotional connection to the deceased

Because no matching pieces to the broken stones were found, it has been conjectured that the missing halves were kept as talismans or souvenirs, showing there could have been an attempt to keep bad luck from following the living or perhaps, the pieces were used as a memento.

"They might have signified a link to the deceased, in the same way that people today might share pieces of a friendship trinket, or place an object into the grave of a loved one," Riel-Salvatore said. "It's the same kind of emotional connection." But whatever the reason for keeping the stones, it is an interesting conclusion.

"This demonstrates the underappreciated interpretive potential of broken pieces," the new study concludes. "Research programs on Paleolithic interments should not limit themselves to the burials themselves, but also explicitly target material recovered from nearby deposits, since, as we have shown here, artifacts as simple as broken rocks can sometimes help us uncover new practices in prehistoric funerary canons."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter