In public, the FBI recommended not filing criminal charges against Clinton on national security grounds. But in private, the Bureau chose to defer to the State Department on whether to recommend anyone to the Justice Department for criminal prosecution on records law violations, the sources said, speaking only on condition of anonymity.

Each email transmission of a government document that was not preserved or turned over to the State Department from Mrs. Clinton's tenure could theoretically be considered a violation of the Federal Records Act, the main law governing preservation of government records and data.

Other federal laws make it a felony to intentionally conceal, remove or destroy federal records as defined under the Act, punishable with a fine and imprisonment of up to three years. A single conviction also carries a devastating impact for anyone looking to work again in government because the law declares that any violator "shall forfeit his office and be disqualified from holding any office under the United States."

The FBI "indirectly documented hundreds, and likely thousands, of violations of the Records Act," one source with direct knowledge of the FBI's investigation told Circa. Using forensics, the FBI recovered from computer drives and other witnesses about 15,000 emails from Mrs. Clinton's private account that dealt with government business, most that had not been turned over by her or her aides, the sources said.

Some of the emails recovered by agents were germane to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests from the public and congressional investigations and had not yet been produced, the sources said.

Accounts from witnesses suggested the efforts to keep Mrs. Clinton's government email communications on a device and server outside the reach of public records laws or congressional oversight were "systemic and intentional" and began as soon as Mrs. Clinton took office in 2009, one source told Circa.

For instance, the sources said agents secured testimony and documents suggesting that Mrs. Clinton's team:

- Was informed in 2009 that she had an obligation under the records law to forward any government-related records contained in private email to a new record preservation system known as SMART but chose not to do so because her office wanted to keep control over "sensitive" messages.

- Was specifically questioned by a technical worker who was involved with her private email server in the Clinton family home in New York whether the arrangement was appropriate for a government official under the federal records law. The worker was assured there were no problems.

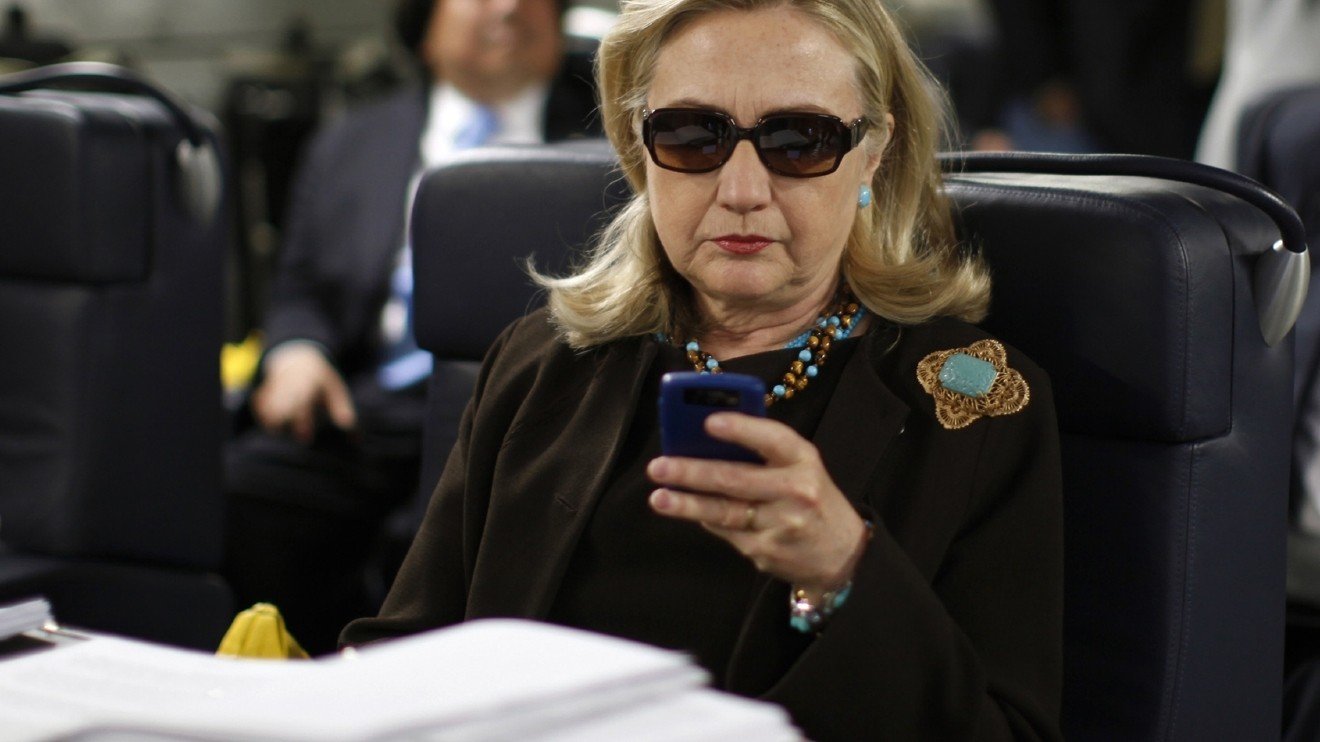

- Wanted to keep her private Blackerry email service because of fears a government email address would be subject to public scrutiny under the Freedom of Information Act.

- Was aware that government officers complying with FOIA requests did not have access to search Mrs. Clinton's private email for responsive records.

- Persisted in allowing her to use private email to conduct State Department business even after a cable was sent under her name in 2011 to all diplomats worldwide urging them to stop using private email because of foreign hacking fears.

- Allowed Clinton to keep using the private email system after after she personally received a 2011 presentation warning of dangers of the private email for government business.

- Failed to preserve private emails from Clinton that clearly involved significant government business, including discussions with Army Gen. David Petraues, the Benghazi tragedy, meeting requests with foreign leaders and the State Department's quadrennial policy and performance review.

- Had prior reason from earlier legal cases involving their conduct to know that emails covering government business were legally required to be preserved and turned over to their agency and the National Archives.

"I don't think so. I know you have the State inspector general here, who's more of an expert on all the department's policies, but at least in some respects, no," he answered. Comey, however, offered no explanation why charges weren't filed.

Attorney General Loretta Lynch said in mid-July that she did not believe her department had assessed whether Clinton or her team violated the Records Act.

"I don't know if that was under the purview of the investigation. I don't recall a specific opinion on that," she said.

The Clinton campaign did not respond to a request for comment. But Mrs. Clinton has said she regrets using private email to conduct official State Department business. Her former chief of staff Cheryl Mills also expressed some regret, saying the Clinton team thought her records would be preserved because her private emails usually went to other government email accounts, but that was mistaken.

Former President Bill Clinton was less apologetic, strongly dismissing Comey's and the FBI's criticism of his wife. "This is the biggest load of bull I ever heard," he said a few weeks ago.

A retired federal prosecutor told Circa the FBI and DOJ could easily have brought a case if the evidence pointed toward intentional violations.

"If you get enough instances of people violating the Federal Records Act and if it's a group of folks then you could look at things like a conspiracy, or a criminal enterprise, that could bump it up to a felony," said

Matt Whitaker, who served as U.S. Attorney for Iowa under President George W. Bush and President Barack Obama and now runs a conservative-leaning government ethics group.

"There are a lot of intentional acts including the setting up of the private email server that probably could go to a question of was this intentional and was this violation of both the records act and the handling of classified material."

Whitaker said he believes a special prosecutor should be appointed to review the Records Act questions because "in this political silly season it appears that the FBI and especially the Department of Justice doesn't have the stomach to pursue the potential charges that emanate from this behavior."

Ronald Hosko, who retired two years ago as the Assistant FBI Director in charge of the bureau's criminal division, agreed Mrs. Clinton's actions at the State Department showed a disregard for her obligation to preserve and protect sensitive government information.

He said such responsibilities were "taken seriously" inside the FBI but that "does not appear to be the case in the State Department under Hillary Clinton. To me, this was a systemic failure at State, top to bottom."

But Hosko said a misdemeanor case wouldn't be sexy enough for an FBI -- stretched by higher terrorism, organized crime and cybersecurity priorities -- to pursue, especially against a candidate leading the presidential race right now in a polarizing election. "The FBI is an agency with finite resources. Seldom do you expend resources when the top available penalty is a misdemeanor," he said. "I'm not saying you don't consider it or contemplate it. I would say you contemplate it if the facts are so compelling and the intent is so overwhelmingly clear, that her desire was to violate that statute."

"But we are in a hyper-politicized time in America. Would the electorate take to that? You have to take that all into consideration."

Sources directly familiar with the FBI's thinking said the bureau was not concerned about the election and did make a short reference to Federal Records Act issues in its final report to the Justice Department.

But it chose to defer to State to decide if criminal charges should be filed. "It's their records and their determination to make," one source said, describing the philosophy that governed the FBI's final decision.

In a noninvestigative report in June, the State Department's internal watchdog concluded Mrs. Clinton was one of only three senior department officials in the last two decades to use a private email account exclusively for government business and that her team did not comply with the record-keeping policies of the Federal Records Act.

Douglas Welty, a spokesman for the State IG, said Thursday the office has no further work planned on the Clinton email scandal. "The OIG has completed its work. The OIG does not comment on whether or not it has referred, or will refer, any particular matter to DOJ," he wrote in an email to Circa.

State Department officials declined comment.

The Federal Records Act was passed by Congress 66 years ago to ensure federal agencies properly managed and maintained government records so they are preserved for historical purposes at the National Archives and for public access and congressional oversight. The law was updated by lawmakers in 2014, legislation that President Obama himself signed.

Since the mid-1990s, the State Department has made clear to its employees that emails were public records covered by the Act, even those sent on their private accounts. In 2009, State employees were instructed if they used personal email for work they had an obligation to upload the emails to a special system called SMART to preserve the records.

Much of the focus during the presidential race has been on the more than 100 emails that moved between Mrs. Clinton and her top aides that contained intelligence classified at the confidential, secret and top-secret level at the time it was transmitted.

Comey announced earlier this summer that Mrs. Clinton's and her staff's handling of intelligence was "extremely careless" but the bureau decided not to request criminal charges for violating national security laws because agents found insufficient evidence of intent and motive.

After her private email system was discovered, Mrs. Clinton eventually turned over 55,000 pages from about 30,000 emails involving State Department work. But FBI officials recovered about 15,000 additional emails on her private account that involved government business by sweeping her old devices and servers or scouring the government emails of other people she corresponded with.

"There was plenty of evidence from our interviews, especially from technical and compliance staff, as to the intention of creating a private email system outside the State Department's record keeping. It was well known, and it persisted even after people raised legal and security concerns," one source told Circa.

At least one witness in the technical community involved in setting up, maintaining or wiping Clinton's email equipment was concerned enough about their legal liability under federal records laws to invoke their Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination during an FBI interview, sources said.

Among the strongest evidence gathered by investigators occurred in late 2010, when Mrs. Clinton was directly approached by one of her top deputies and informed that her government emails from her private account were not reaching State Department officials and possibly were going to spam. Mrs. Clinton was encouraged to get an official State email address.

Mrs. Clinton told her deputy she was willing to get a govermment email address if she could be assured her personal emails wouldn't be "accessible" to the public. Rather than create the government email address, State officials went to a technical person maintaining her private server and made adjustments to the server to ensure emails wouldn't be treated by the agency's email screening systems as spam, the sources said.

Around the same time, two information management employees inside State began raising concerns that material in Clinton's personal email server likely contained government records that needed to be preserved under the Federal Records Act. One raised the concern to a supervisor at a staff meeting but was scolded and eventually told never to raise the issue of Secretary Clinton's personal email account again, according to the sources.

Agents also found evidence Mrs. Clinton herself was acutely aware of the security and legal dangers of using her private Blackberry to conduct government business. For instance:

- In 2009, Mrs. Clinton and her chief of staff were briefed in a classified memo from the Assistant Secratary for Diplomatic Security on the security dangers of private Blackberry service and the secretary of state responded to that official a few days later that she "gets it."

- Mrs. Clinton received a second classified email in March 2011 about foreign government hacking attempts specifically aimed at State Department officials. The memo included this warning: "We also urge Department users to minimize the use of personal Web email for business" citing evidence of "compromised home systems." A version of that briefing was found in Mrs. Clinton's personal files at State.

- In June 2011, a cable entitled "securing personal email accounts" was sent to all U.S. diplomatic posts worldwide under Clinton's own name that highlighted growing cybersecurity threats and specifically warned "to avoid conducting official department business from your personal email accounts."

- By that time, officials maintaining Mrs. Clinton's private email server had detected attempts to hack into it but still she persisted in using the private email to conduct government business.

In 2011, shortly after the information management staff raised concerns about her private email, Clinton's top aides discussed replacing her private Blackberry with a government-owned device, but that idea was scrapped after a top aide warned the materials on the government Blackberry would be subject to FOIA.

"You should be aware that any email would go through the Department's infrastructure and be subject to FOIA searches," a top State official warned.

The government Blackberry was never issued.

When Mills, Clinton's former chief of staff, was recently deposed in a civil lawsuit over FOIA practices brought by the watchdog group Judicial Watch, she admitted that State Department FOIA officers would not have had access to Mrs. Clinton's private email to search for responsive records.

"No is the answer," Mills testified. "I don't think I reflected on were there occasions where there might still be something with respect to a personal e-mail where someone had either e-mailed me or I had responded back or the system had been down and we ultimately needed to use it, that there was information that hadn't been captured. And I wish it had."

We are probably seeing more of Secretary Clinton's emails now than we would have if they had actually been stored at State Department...But it's not just the State Department. Experts say the federal government as a whole has a serious problem when it comes to maintaining electronic records.

— Patrice McDermott

Patrice McDermott, executive director of the non-partisan OpentheGovernment.org, told Circa that federal agencies have largely failed to preserve electronic records since the government switched to emails in the 1980s. That's nearly four decades of records that, for the most part, haven't been fully archived.

Regret for lost government records isn't new to the Clinton political machine. Both Mills and Mrs. Clinton were mentioned in a lawsuit in the late 1990s during Bill Clinton's presidency over the loss of more than 1 million White House emails that were not saved for FOIA, congressional or criminal investigations. The Clinton White House blamed a technical error for the loss of the records.

But subsequent litigation by the Judicial Watch group found evidence that a White House official disabled the archiving function for White House emails. A federal judge sharply criticized the Clinton White House for what he called a "fiasco" and singled out Mills, who had been a deputy White House counsel for Bill Clinton, for having "failed miserably" to resolve the problem or give the court accurate information.

In another embarrassment, Sandy Berger, President Clinton's national security adviser and a longtime confident of both Bill and Hillary Clinton, was caught a decade ago trying to secret classified information about terrorism out of the National Archives in his socks. He pleaded guilty and apologized. Berger died last December after a brief illness.

But Republicans have had their fair share of records act violations too. Most famously in the late 1980s, Fawn Hall, secretary to Marine Corps Lt. Col. Oliver North -- one of President Ronald Reagan's national security advisers -- smuggled documents related to the Iran-Contra affair out of the White House in her boots and shredded them. And Clinton is not even the first a secretary of state to use a private email account. George W. Bush's secretary Colin Powell had one too.

Whether Secretary Clinton's deleted her emails with the intention of evading records laws or not, the FBI and other experts agree conducting government business on a private email account was reckless.

"It was irresponsible of state to let her do it," McDermott said. "I know it's difficult to manage the head of your agency and tell her she can't do something. But, the attorneys should have told her she cant do this."

Reader Comments