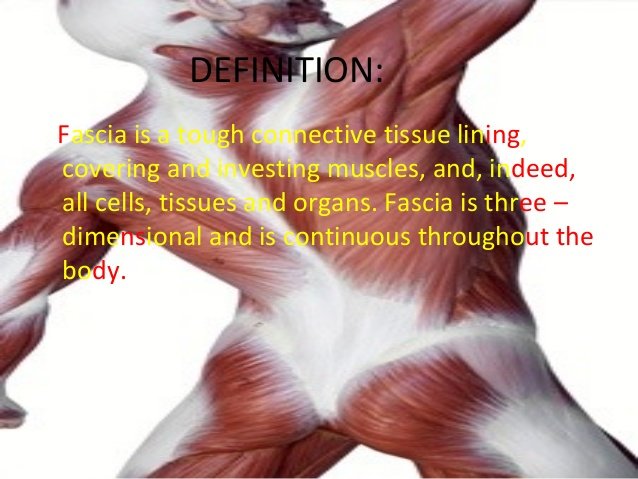

Let's start with the basics: What is fascia?

At its most basic definition: Fascia is connective tissue. It's kind of like a pomegranate—your skin is the outer shell, while your organs, muscles, and bones are the juicy seeds—all the white parts and pockets are fascia.

What does healthy fascia look like?

Healthy fascia is well hydrated and has a gel-like consistency. Its fluid state allows it to move and glide without resistance.

So what does unhealthy fascia look like?

Unhealthy fascia is tight; it's hardened and crystallized. And when the fascia tightens down, fluid can't move through it. Have you ever noticed how when you wake up in the morning, you're quite stiff? That's because little adhesions have built up on your fascia overnight.

Would you say fascia is malleable?

Yes—fascia is a shape-shifter. It is constantly reworking itself. They say you can tell what someone does for a living by their fascia, because the fascia will reshape itself to support a person's habits.

What does fascia like?

Fascia likes variety, so the greater the variety the better. And there are a lot of different ways to create that variety. An easy way is temporally. So, for instance, if you are lifting weights, you can do the exact same set with the exact same weight, lifting faster one day and slower another. This gives you a completely different workout. And the fascia loves that you're changing things.

So what does fascia not like?

Fascia hates repetition—like the keyboard, this is where you see carpal tunnel and such. So highly repetitive movements are the absolute worst things you can do for fascia. It causes the fascia to grip and start laying down supporting cables to help the muscles. And even a sport can be highly repetitive. So the trick is changing it up—like lifting at different speeds per my prior suggestion or choosing a new activity to try.

And how does bad posture impact fascia?

There's a saying by Thomas Myers that movement becomes habit, habit becomes posture, posture becomes structure. So when you have bad posture that causes a muscle to hold for a long period of time, the body starts laying down fascia, like metal cables, to take the load off the muscles. And what started as a movement quickly becomes a habit, which then becomes your posture, which eventually becomes a structure. And by the time it's structure, there's not much you can do.

How do things like stress or trauma affect fascia?

Fascia responds dynamically to stress, and it can change to be more crystalline and rigid or it can change to be more fluid and gel-like. And it happens surprisingly quickly. So when you are relaxed, it turns into more of a gel and you become more flexible and when you're stressed or under fear or trauma, it tightens up under pressure to protect you.

Can fascia recover from the impact of chronic stress or bad posture?

Well the sooner you catch it, the more freedom you have. At the level of movement, it's very easy to correct. Habits are a little tougher. And posture is a pain. To get someone to change their posture, they're going to have to work really, really hard to correct it. But if they don't, then they will move into structural problems. Bones reshape and their whole body will reshape to support that new posture—and at that point posture is actually becoming a structural problem, not muscular.

Comment: More information about posture:

So how should we combat this?

There's a theory that fascia starts to change if you hold any position for 17 minutes or longer. So you can have bad posture for 15 minutes as long as you take a break, get up and stretch it out. But if you go for 20 minutes, your body starts laying down fascia to support the muscles. So one of the easiest ways to help yourself is to get a little timer and set it on your desk and when the timer goes off every 15 minutes, stop for a second, lift your arms up, roll out your shoulders, and then slip right back into what you were doing. Gradually, your body will start to think, oh that feels so good, and you won't need the alarm anymore.

What's the latest fascia discovery or theory?

They are finding now that the fascia is highly integrated with the nerves. No one realized this before. They just thought it was connective tissue and they never really took a closer look at it. But now they believe that fascia runs through the nerves, as well as the muscles. It's everywhere. And they believe there is a higher density of nerves and nerve receptors in the fascia than there are in the retina. So this means your entire body is conscious and taking in information and processing it. And that's led to a theory that the feedback from the fascial system is the key to balance. So practicing balance with the eyes closed can really help increase our consciousness of the whole body and the dialogue between fascia and the nerves.

What is the one thing you want readers to remember about fascia?

Fascia is fluid. Hydrate it and it will be happy.

So how do you keep fascia in the healthy, fluid-like state?

Hydration is essential to the fascia, but you can't necessarily chug a liter of water to do the job. The fluid has to work its way through the fascia, but unlike blood and the heart, for example, there's nothing pumping it through the body. So it's the types of movements and stretches you do that get fluid moving into the fascia. The best thing in the world is any type of rhythmic contraction and relaxing action. Stretching, turning upside down—all of these help.

Knowing fascia can be stiff in the morning, what's the first thing you do when the alarm clock goes off?

We should watch animals, because every time they wake up they stretch really big and yawn. And that's good! So my favorite thing to do is to set my alarm about an hour before I need to get up and then when the alarm goes off, I hit snooze. And I just lay, kind of like in savasana. And usually after about 10 or 15 breaths I'll get the urge to stretch. I keep it small and contained to just the core and take a few breaths. And usually after a minute or two, it's kind of like a yawn, where the urge comes up from somewhere deep within and I get the urge to stretch again. And I keep doing that until I'm wide awake and ready to start the day.

So what does fascia not like?

Fascia doesn't like to stay static for too long, it immobilizes. Inactivity can cross-bond with the fascia sheath, so when you don't stretch, instead of gliding inside that nice smooth facial sheet, you get oxidation and the nerve gets attached to the sheath and it can't move freely. Other things like isolating muscles, training in the same tempos, or training too fast are also bad.

So if you're a runner, for example, don't run everyday?

Well if you did, run differently. Run with hills one day and on flat terrain the next. Try running for less time, but faster. And do a leisurely run the next day. The greater the variety, the healthier the fascia becomes.

You say to always choose boredom over pain—how do you know when you're pushing yourself too far as far as fascia is concerned?

The longer I have practiced yoga, the more I am coming to believe in subtlety and the power of less. I believe in focusing on efficiency over brute force, because with very few exceptions, pain is never good. And when you are pushing into discomfort, your brain starts signaling to muscles to tighten up. And with any type of stress or strain, the fascia tends to grip down and crystallize, which is the worst thing.

And does it stay that way?

When you work with people with chronic pain, it seems to be locked down. But I think initially, it grips at first and then releases when the pain goes away. But if that pain comes too often, too quickly, it goes "why bother relaxing?" And it gets into this frozen state, which is very unhealthy.

So when you injure any one of these anatomy parts—be it bone, tendon, ligament, muscle, fascia—they all have to heal together?

Yes, an injury in one area affects your entire body. IT bands are a good example. Many runners suffer from tight IT bands. If you palpate in the mid-thoracic spine, it will be hard and painful. And if you put two tennis balls there and lay on them and spend a half hour working your way down your back, when you get to the mid-thoracic area to release, the IT bands will release. Because the problem wasn't the IT bands, it was the mid-thoracic pulling that was pulling on the IT bands and causing the pain.

As far as tennis/lacrosse balls, foam rolling, etc., what do you recommend for daily upkeep?

Those are all great. Typically what I do is use a foam roll or tennis balls once or twice a week. If I have a really key area, I might do two or three days in a row, but I don't do it daily. And remember, you want variety. So doing the same thing everyday won't be good for the fascia. Roll along the fibers one day and across them the next. I would also vary the softness and firmness of your roller.

I've found that when using tennis balls, I can sometimes hit resistance that is pretty painful. How do you know when to push through or back off?

There's a fine balance there. And one of the ways I know what edge I'm at of that equation is by my ability to surrender and breathe. When I get to an area that is tight, I try to send my consciousness to it by relaxing the area and breathing into it. So it's not about letting the ball break up the fascia, it's about the ball bringing my attention to that area and then I use my breath and heaviness to lean into it and release it. And if I can't, that's my indication that I'm at too high of a level. If my body refuses to relax into it, then I back off, going to a smaller ball or softer roller to soften it and then I try it again.

About the authors

Laci Mosier is a copywriter living and loving in Austin, Texas. She and her one-eyed pirate dog live for exploring and discovering life's magic. She is most inspired by yoga, running, Kundalini meditation, good books, great jams and even better coffee. Getting lost is where she is most often found. Follow her on the Twittersphere or Instagram.

Charles Maclnerney is an E-RYT-500-hour certified yoga instructor living and teaching in Austin, Texas. He began practicing yoga at 11 years old and has spent the last 44 years dedicated to the practice. He teaches a fascia workshop and is a co-founder of the Living Yoga Teacher Training Program. For information about the variety of yoga retreats that Charles offers throughout the year, please visit his website: www.yogateacher.com or email him.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter