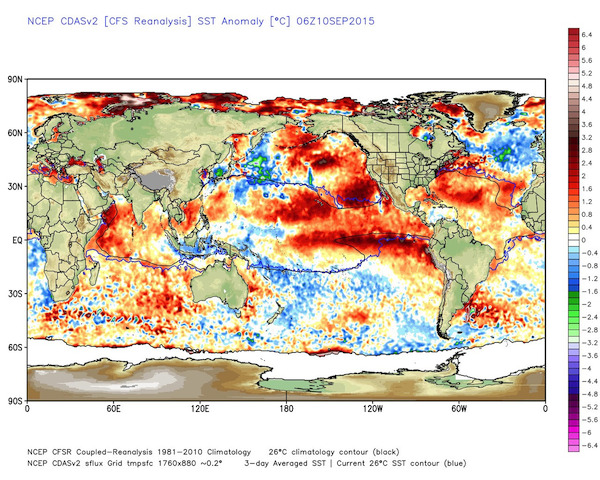

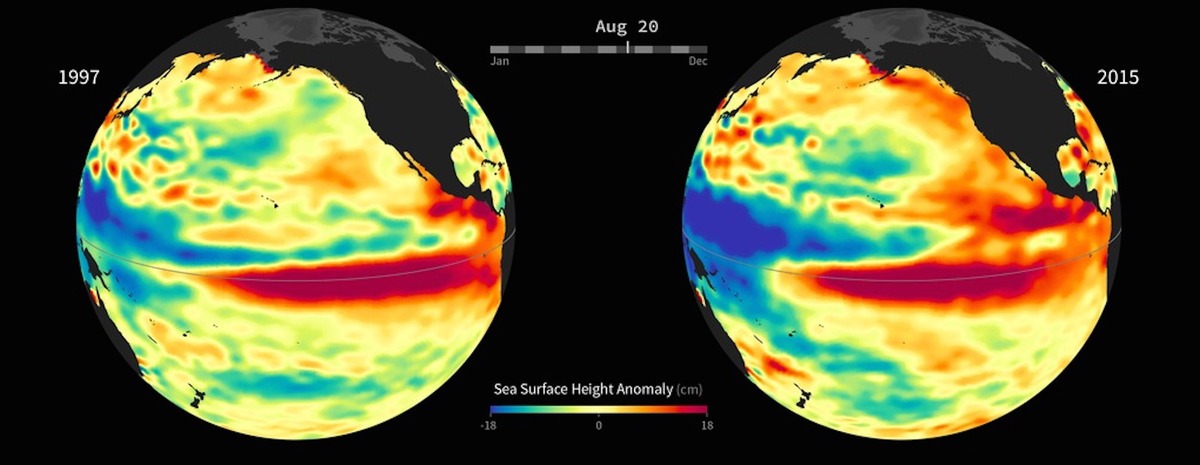

It's possible that the ongoing event, which should peak in the next several months, will eclipse the mother of all El Niño events, which occurred in 1997-98, as well as another monster El Niño that occurred in 1982-83.

That is not assured, however, as it's not quite there yet.

"By any measure, '97 is stronger" so far, said Mike Halpert, the deputy director of the CPC, during a conference call with reporters.

In a forecast update on Thursday, forecasters at CPC said there is at least a 95% chance that El Niño will last through the winter, which is up from a "greater than 90% chance" in the August update. This is about as close as climate forecasters get to a sure bet, given their tendency to hedge slightly just in case something unexpected happens.

In addition, forecasters, relying on readings from a network of buoys bobbing in the Pacific and computer models whirring away in Maryland, Colorado, Australia and elsewhere, are unanimous in saying that this event is and will continue to be strong.

What everyone wants to know: What will El Niño bring?

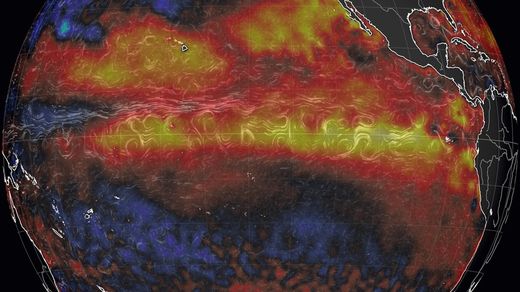

El Niño events are characterized by unusually mild ocean temperatures in the central and eastern equatorial tropical Pacific Ocean, along with a slowing or even a complete reversal of the normal east-to-west flow of trade winds from the coast of Panama to the many islands of Indonesia.

In some ways, you can think of El Niño as a rock suddenly placed in the middle of a river. It will create waves downstream that weren't there before.

El Niño events have consequences far beyond rain and snowfall amounts. Researchers have uncovered links between El Niño, and its opposite sibling La Niña, and cholera rates in Bangladesh, while some countries see significant changes in the price of key food staples as fish move in response to the warming waters.

So the big question for more than a billion people around the world, from East Africa to India to the U.S. is what this event will actually mean for them.

Will central and southern California experience torrential rain and mudslides this winter, as occurred during the 1997-98 event?

Or will El Niño interact in strange ways with unusually mild ocean temperatures in the northeast Pacific and from Hawaii to California, affectionately known to meteorologists as "The Blob," and make storms even wetter but warmer, yielding more mountain rains than snows?

Halpert told reporters on a conference call that the strongest events, such as this one, tend to yield above average winter rainfall in southern California, with six of the six "strong" events in the historical record yielding such a result. That's far from a guarantee, however, he said.

California has been stuck in a historic drought during the past four years, and Kevin Werner, the western regional climate services director at the National Center for Environmental Information, said El Niño tends to raise the odds of wetter than average conditions in the Southwest, but such a relationship does not exist in major water source regions such as central California and the northern Colorado River Basin.

The bottom line is that for this winter to completely erase the ongoing drought, the season would have to have about two-and-a-half to three times the average precipitation for the water year. The wettest water year on record, in 1983, had 1.9 times the average precipitation, Werner said.

For example, in California, the central Sierra Nevada mountains has a precipitation deficit of 71 inches since 2011.

For the U.S. overall this winter, based in large part on presence of the strong El Niño, forecasters are favoring above average precipitation in the southern parts of the U.S., from California to Florida. Forecasts show below average precipitation for the northern Rockies, Great Lakes, western Alaska and Hawaii, and with above average temperatures in Alaska, Hawaii and the northern tier of the country.

Interestingly, the U.S. tends to benefit economically from El Niño events, in part because of reduced heating demand and above average precipitation.

Many other nations are not so lucky, however. In the western Pacific, for example, areas from Indonesia to parts of Australia face a heightened odds of drought, as tropical precipitation patterns shift. This is already developing to some extent.

According to Australia's Bureau of Meteorology, El Niño is typically associated with below-average winter and spring rainfall over eastern Australia. Conditions in the Indian Ocean also influence Australia's climate to a significant extent.

Comment: According to this report from the NOAA, the 1997/98 El Niño, was one of the most significant climatic events of the century, and produced extreme weather worldwide. During this El Niño, temperature and precipitation records were broken across the United States. Many areas suffered heavy flooding, and the U.S. experienced a series of severe tornadoes. Elsewhere around the world, El Niño contributed to major droughts and wildfire in Mexico, Indonesia and Brazil; devastating floods in South America; and massive coral bleaching from Panama to Africa to Australia's Great Barrier Reef.

'Double El Niño? Rare weather phenomenon about to change our world?