OF THE

TIMES

I've had enough of someone else's propaganda. I'm for truth, no matter who tells it. I'm for justice, no matter who it's for or against. I'm a human being first and foremost, and as such I am for whoever and whatever benefits humanity as a whole.

Perhaps some people may understand now why the Zionists have said long ago: constant remembrance of the holocaust is necessary in order to bring...

This should pinpoint some things [Link]

Well the Israelis are doing a pretty good job of chanting slogans Like Kill all the Gazan's and kill all the Iranians. What's the difference. The...

"To The Last Ukrainian" Sep, 2023 . [Link]

They hate people have an alternative information source they have no control of.

To submit an article for publication, see our Submission Guidelines

Reader comments do not necessarily reflect the views of the volunteers, editors, and directors of SOTT.net or the Quantum Future Group.

Some icons on this site were created by: Afterglow, Aha-Soft, AntialiasFactory, artdesigner.lv, Artura, DailyOverview, Everaldo, GraphicsFuel, IconFactory, Iconka, IconShock, Icons-Land, i-love-icons, KDE-look.org, Klukeart, mugenb16, Map Icons Collection, PetshopBoxStudio, VisualPharm, wbeiruti, WebIconset

Powered by PikaJS 🐁 and In·Site

Original content © 2002-2024 by Sott.net/Signs of the Times. See: FAIR USE NOTICE

This Wall Street article, published today, is focusing on Germany when the fire is in Portugal. They don't want that news to rile the markets anymore than it already has.

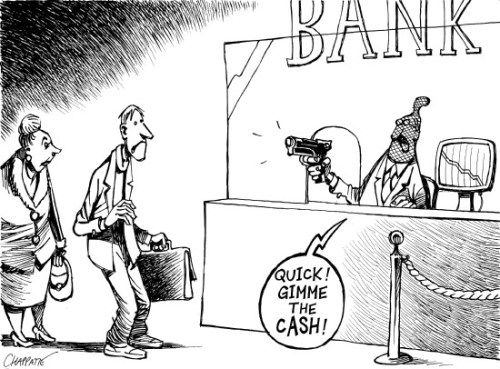

The second largest bank in Portugal, Banco Espirito Santo, just went Lehman Bros today. They are counterparty to a ton of derivatives. This could be that black swan event that causes the wheels to come off the global central banking casino. It deserves serious watching. Late in the day the WSJ finally took notice: Markets Tumble on Portuguese Bank Woes [Link]