© Unknown

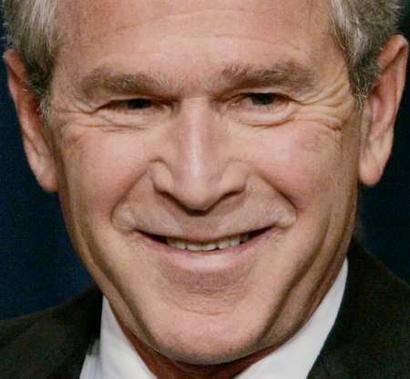

While President George W Bush heaped praise on Thailand, which he recognized as the United States' oldest ally in Asia, a diplomatic debacle played out behind the scenes.

Bush's farewell address to Asia was made symbolically in Thailand to highlight the 175-year anniversary of US-Thai diplomatic ties while also touting his administration's many self-professed diplomatic successes in the region, including the widespread promotion of liberty, law and democracy.

Left unaddressed were tensions in US-Thai bilateral ties, which have risen sharply in the wake of the September 2006 military coup that ousted democratically elected prime minister Thaksin

Shinawatra and sparked accusations among the fallen premier's supporters that Washington has taken sides with the military and its political allies in the country's ongoing political conflict.

On the podium, Bush congratulated Thailand on restoring democracy, but conspicuously refrained from commenting on the country's 16-month period of military rule and the shadow the Thai military still casts over the political scene. Behind the scenes, several key Thaksin allies were not invited to the high-profile event and Thaksin himself was conspicuously absent, traveling outside of the country.

Bush's handlers declined, even after heavy Thai government lobbying, to allow for a question-and-answer session after his address, which inevitably would have led to queries about the US's view of the coup, the military-drafted constitution and the likely US reaction to any future military interventions, which some fear may be in the offing should Thai politics deteriorate into street violence.

Thai government insiders also contended that Bush failed after heavy foreign ministry lobbying to arrange a meeting with King Bhumibol Adulyadej, who was in residence at his seaside palace in Hua Hin, about 200 kilometers south of Bangkok. Government sources say that's because Hua Hin's airport lacks the runway facilities to accommodate Bush's jet. The 80-year-old and highly respected monarch notably did not opt to travel to Bangkok to greet Bush.

The diplomatic snafus come against perceptions among certain Thaksin supporters that Bush's emissaries in Thailand, despite pro forma US public statements condemning the temporary suspension of democracy, too swiftly and too warmly embraced the military coup-makers, many of whom are known to have close ties to top US officials.

While the US suspended a small amount of military aid to Thailand, it followed through on its annual Cobra Gold joint military exercises, the region's largest, while the Thai military was in power. Peeved Thaksin supporters recall comments Bush made at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation meeting in Hanoi soon after the 2006 coup, where in comparison he noted that Singapore wasn't exactly democratic but was nonetheless still a good US friend.

Two-track diplomacyUS diplomacy with Thailand has long run on separate civilian and military tracks and has often prioritized strategic interest over other policy goals. From 1947 to 1958, for instance, the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) was intimately involved in Thai political outcomes and America frequently supported suppression of Thai government opponents when it served Washington's interests. [1]

In the 1960s and 1970s, the US provided assistance to repressive military governments and built the road infrastructure that helped Thai troops battle communist insurgents. Now, nowhere are the conflicted US policies of democracy promotion and strategic positioning more glaringly apparent than in Thailand. The Bush administration's global counter-terrorism campaign, which he highlighted heavily in his farewell speech, recast the cause for US military involvement in Southeast Asia, including in Thailand.

Throughout the 1970s, 1980s and into the 1990s, Washington justified, and several regional countries welcomed, the US military role in counterbalancing China's communist and perceived expansionist threat. When China later effectively ditched communism for capitalism and diplomatically and economically engaged the region, the US's past raison d'etre for a strong strategic presence diminished.

Keen to counterbalance China's rising regional influence, which many analysts view as coming at the expense of the US, the Bush administration highlighted the risk of global terrorism to Southeast Asia - even in backwater countries like Cambodia, where security analysts say the terror threat is virtually nonexistent - as new justification for building strategic ties.

Thailand has been crucial in that campaign and the US in 2003 upgraded Bangkok to a major non-North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) ally, a status that confers special military and financial advantages upon the country. US intelligence agents already positioned in the Thai Supreme Command's so-called JSEC units, according to one government source, were able to refocus their clandestine collaborations.

Thailand also agreed in 2001 to establish a more specific joint Counter-terrorism Intelligence Center (CTIC) in Bangkok, where CIA agents and their Thai spy counterparts continue to gather and share information about regional terror groups. That unit was reportedly responsible for the 2003 sting operation that netted terror suspect Riduan Isamuddin, or Hambali, an alleged high-level al-Qaeda operative who was on the run in central Thailand.

Security over libertyThat arrest, which Bush praised in a 2003 visit to Thailand, was also highly controversial and critics contend represented a violation of Thai sovereignty because the suspect was whisked by the Americans to an undisclosed third country before standing trial in Thailand. The CIA also controversially tapped Thailand to host one of its notorious secret prison sites, to where at least two Pakistani terror suspects were transported and apparently tortured as part of Bush's controversial rendition program.

Thailand has never publicly acknowledged the existence of the secret prison, but US officials did after the Washington Post broke the story. Rights groups have maintained that the US tapped Thailand for the site exactly because Bangkok has not ratified the United Nations Convention Against Torture. Thailand has also passed US-influenced anti-terrorism legislation in 2003, which allows for detention without trial of terror suspects.

These strategic assets have arguably compromised the US's ability and willingness to speak out against the 2006 coup and the military's continued influence over Thai politics. The US's heavy in-country intelligence presence has also bred still-unfounded suspicions among Thaksin supporters that Washington had foreknowledge of the coup, which was orchestrated by several Thai security and military officials with close and long-time ties to Washington.

They include CIA-trained Squadron Leader Prasong Soonsiri and the US-trained General Winai Phattiyakul, former director of the Directorate of Joint Intelligence at the Supreme Command's headquarters where US intelligence officials are allegedly in residence. US security officials and former US ambassador to Thailand Ralph "Skip" Boyce are also known to have generational ties to Privy Council president Prem Tinsulanonda, who Thaksin's supporters have accused of masterminding the 2006 putsch - charges the elder statesman has consistently denied.

Thaksin has never spoken publicly about the role of the US, but his close associates say he was miffed by Washington's response to the coup. It was no coincidence, they note, that he chose to air from China his critical messages about the military government, while his high-priced lobbying efforts in Washington failed to generate much official sympathy as a deposed democratic leader at the White House or Capitol Hill.

While Thaksin fully cooperated with Bush's terror fight, he simultaneously moved to put Thailand's relations with the US and China on a more equal footing. That included new strategic overtures towards Beijing that allowed each side to observe the other's military exercises and the staging of their first joint naval exercises in 2005, which produced an opening to undermine the US's near monopoly on military-to-military training in Thailand. Thaksin also increased Thailand's arms purchases from China during his tenure.

Bush said in his speech that US diplomacy in Asia had transcended its previous "zero sum" calculations and that a prosperous and secure region required both countries' participation. Whether Thaksin's moves to embrace China influenced the tepid response of the US to the 2006 coup is still a matter of conjecture. But the fact that many in Thaksin's camp believe Bush's government put strategic interests before its commitment to uphold democracy means the US could lose out should Thaksin ever return to power.

Note

1. See Daniel Fineman's A Special Relationship: The United States and Military Government in Thailand, 1947-58, University of Hawaii Press, 1997.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter