- The structures were captured using a technique dubbed 'Exchange-PAINT'

- DNA is attached to antibodies that recognise a specific cellular structure

- DNA with fluorescent tags are introduced and bind to partner structure

- This is first time system has been able to take images less than 10nm apart

- Images like this could uncover new ways to diagnose disease, track its progress, or monitor the effectiveness of therapies at a cellular level

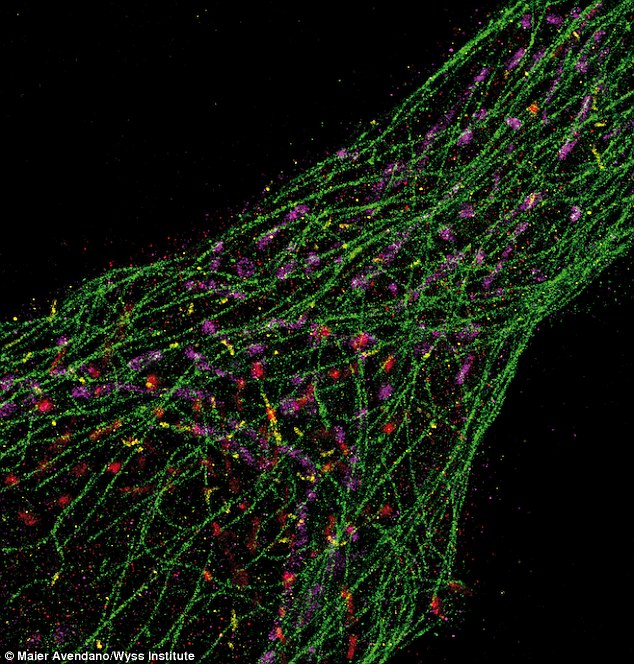

It might seem like a piece of abstract art, but in reality these intricate patterns are the tiny scaffolds and components that make up a human cell.

Inside each cell is a huge range of molecular machinery that can resemble a busy construction site, with different types of these tiny cellular workers coming and going.

This ultrasharp image uses a new method to simultaneously resolve microtubules (green), mitochondria (purple), Golgi apparatus (red), and peroxisomes (yellow) from a single human cell. Each of these components works together to make the cell function

Researchers in Boston were able to capture these tiny structures using strands of custom-built DNA in a microscopy technique dubbed 'Exchange-PAINT'.

The new technique could enable scientists to generate snapshots of dozens of different biomolecules at once in a single human cell.

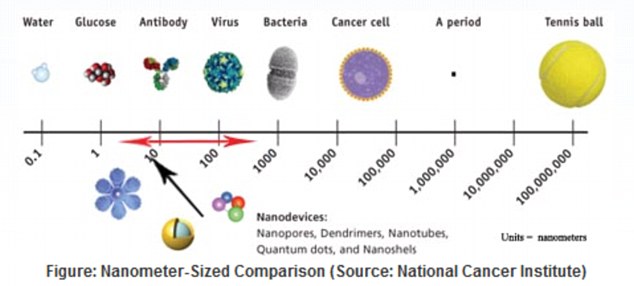

This is the first time researchers have been able to develop an imaging system that can capture structures less than 10 nanometres apart - or the size of an antibody.

Scientists hope images like this will help uncover new ways to diagnose disease, track its progress, or monitor the effectiveness of therapies at a cellular level.

How the Exchange-Paint technique worksToday's methods typically only spot at most three or four types of molecular machinery simultaneously.

Exchange-PAINT relies on the fact that DNA strands with the correct sequence of letters, or nucleotides, bind specifically to partner strands with complementary sequences.

The researchers label a biomolecule they want to see with a DNA tag, then add to the solution a partner strand carrying a fluorescent dye that lights up only when the two strands pair up.

When that partner strand binds the tagged biomolecule, it lights up, causing the biomolecule to 'blink' at a precise rate the researchers can control.

The researchers use this blinking to obtain ultra-sharp images. They then repeat the process to see a second target, a third, and so on.

Researchers overlay the resulting images to create a composite picture in which each biomolecule - each cellular worker - is assigned a different colour.

This allows them to create false-colour images that simultaneously show many types of biomolecules

And these false-colour images allow them to spot enough cellular workers at once to capture the entire scene

But to truly understand complex cellular functions, it's important to be able to see most or all of those workers at once, said Peng Yin, assistant professor of Systems Biology at Harvard Medical School.

'If you can see only a few things at a time, you are missing the big picture,' Dr Yin said.

To capture ultra-sharp images of biomolecules, researchers had to overcome laws of physics that hindered microscopists for most of the last century.

When two objects are closer than about 200 nanometres apart - about one five-hundredth the width of a human hair - they cannot be distinguished using a traditional light microscope.

The viewer sees one blurry blob where in reality there are two objects.

Since the mid-1990s, scientists have developed several ways to overcome this problem using combinations of specialised optics, special fluorescent proteins or dyes that tag cellular components.

Ralf Jungmann at Harvard Medical School helped develop one of those super-resolution methods, called DNA-PAINT, as a graduate student.

DNA-PAINT can create ultra-sharp snapshots of up to three cellular workers at once by labelling them with different coloured dyes.

To visualise cellular job sites with crews of dozens of cellular workers, Dr Yin's team modified DNA-PAINT to create a new method called Exchange-PAINT.

The researchers label a biomolecule they want to see with a DNA tag, then add to the solution a partner strand carrying a fluorescent dye that lights up only when the two strands pair up.

When that partner strand binds the tagged biomolecule, it lights up, causing the biomolecule to 'blink' at a precise rate the researchers can control.

The researchers use this blinking to obtain ultra-sharp images. They then repeat the process to see a second target, a third, and so on.

Researchers overlay the resulting images to create a composite picture in which each biomolecule - each cellular worker - is assigned a different colour.

And these false-colour images allow them to spot enough cellular workers at once to capture the entire scene.

To test Exchange-PAINT, the researchers created 10 unique pieces of folded DNA, or DNA origami, which resembled the numerals 0 through 9.

The team was able to use Exchange-PAINT to capture clear images of the 10 different types of miniscule DNA origami structures in one image.

They also used the method to capture detailed, ultra-sharp images of fixed human cells, with each colour tagging an important cellular component.

Dr Yin expects the method, with further development, will be able to visualise dozens of cellular components at once.

'I expect insights from those experiments to lead to new ways to diagnose and monitor disease,' said Wyss Institute Founding Director Don Ingber.

Seems I've heard that before: "Scientists hope images like this will help uncover new ways to diagnose disease, track its progess, or monitor the effectiveness of therapies at a cellular level."

Must be the marketing dept that writes up these reports... national media... same thing, promotions, propaganda and whatnot.