© Unknown

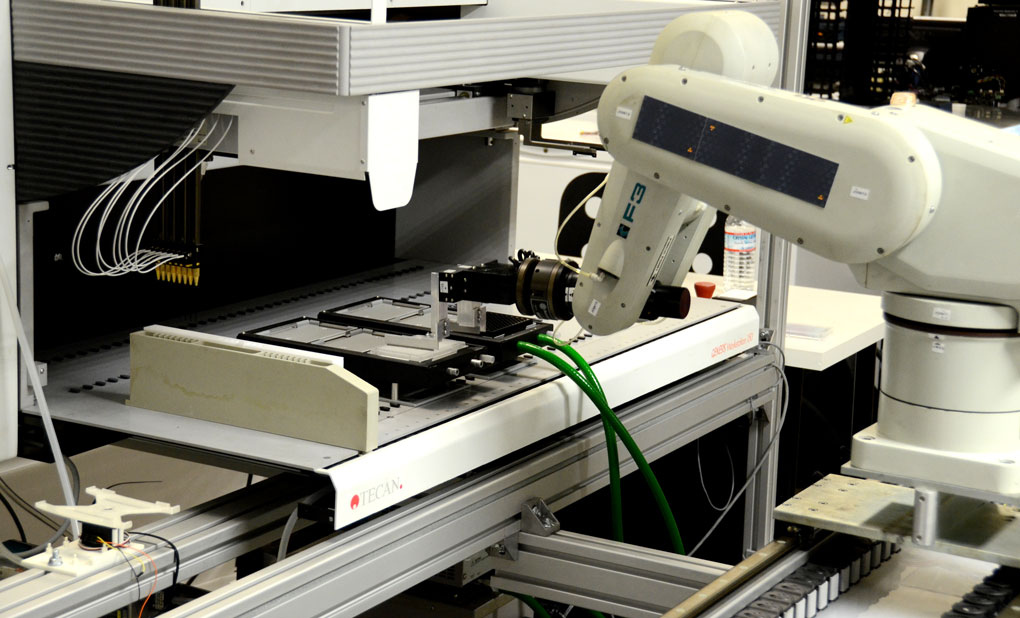

Inside a nondescript office park in Silicon Valley, a robotic arm is running a test. With rapid, precise movements, the arm pipettes colored liquids into wells on a tray. Within a few minutes its work is done: the arm has pipetted the logo for

Transcriptic, a fast-growing, Google Ventures-backed robotics startup that could upend the way biologists do their research.

Transcriptic's small team is calibrating the robot arm, which serves as the linchpin of the company's efforts to transform life-science research by making it cheaper and more accessible. Scientists send in raw materials - DNA, for example, or biopsied mouse tissue - and tell Transcriptic what to do with it. Costs for the service start at a few dollars per test, and the turnaround time is typically limited only by how long it takes for cells to divide.

The company began taking orders from all comers earlier this year, selling services including cell cloning, genotyping, and biobanking. Early customers include Stanford; the California Institute of Technology; the University of California, San Diego; and the University of Chicago. Since July, the number of customers has roughly doubled every month. The heart of Transcriptic is what it calls the "work cell," the automated lab where the robot arm performs its duties: manipulating samples using the various connected machines that run protocols.

The company had never previously allowed journalists inside its walls. But recently, Transcriptic invited

The Verge to come look behind the curtain - the work cell is normally hidden behind an actual, physical curtain - to see how the company is using robotics to do work that has previously been the province of PhDs.

© Unknown

"At first I was like, this is kind of crazy," says Blake Byers, a partner at Google Ventures, which led a $1.2 million seed investment in Transcriptic last December. "Are you really going to automate all the nuance that is biology?" But Byers, who earned his PhD in bioengineering from Stanford, came around in part because of his own experiences in labs. "It's a fact that I've wasted many hours of my life moving my hand around to transport small volumes of liquid from one tube to another.""I've wasted many hours of my life moving my hand around to transport small volumes of liquid from one tube to another."

© Unknown

That feeling was familiar to Max Hodak, the 24-year-old entrepreneur who founded Transcriptic nearly two years ago. A native of New York City, Hodak

built and sold his previous startup before he could legally drink. That company, MyFit, focused on helping students identify the right colleges. But Hodak spent much of his time as an undergraduate at Duke University researching brain-machine interfaces, and saw firsthand how much time in the lab is wasted. Sometimes researchers have to wait days or weeks to use a particular machine. Other times they spend days on end doing work that is essentially robotic - transferring liquid from one small well to another. And if they should make a mistake, they might not even notice for weeks.

Hodak's proposed solution is a company that tries to do for biologists what Amazon Web Services does for information technology: by making basic services cheap and accessible over the web, it lets customers try things that were not previously possible. "Most of biology is in the analysis," Hodak says inside his office. "The humans don't add value in going to the bench and doing this stuff by hand. Humans add value by writing papers and running creative experiments that test sophisticated hypotheses. But that's not what we're spending most of our time on as a field."

© Unknown

For now, Transcriptic is a lean operation, with nine people working in a small two-story office that contains the company's lone work cell. To conserve costs, employees build much of their own equipment using 3D printing and laser-cutting tools. Among other things, they built an automated freezer that would have cost them $400,000 retail for about $8,000.

The company's main competitors are the nation's 1,100 contract research organizations, a multibillion-dollar industry that provides third-party support for clinical studies and trials. But Hodak doesn't want his customers to merely run the occasional test - he wants them to build whole new companies and services using his robots. Eventually, he says, two people will be able to found their own biotech company working from a coffee shop: Transcriptic runs the tests, and the coffeeshop biologists sell the analysis.

It's an idea that has some appeal to biologists contacted by

The Verge. "If you go into a lab, they basically look the same as they did in the 1980s, except for computers," says Josiah Zayner, a biochemist at the University of Chicago. (Among other experiments, Zayner

has used proteins to create a new musical instrument.) Zayner is frustrated that computers in his lab still aren't networked - checking in on one of them requires pulling the data off a USB drive. It seems archaic, given the progress of cloud computing. "I really think this is a step in the correct direction," he says of Transcriptic. "Imagine if science was industrialized, what could be accomplished."

"Imagine if science was industrialized, what could be accomplished."

Chaitan Khosla, professor of chemistry and chemical engineering at Stanford, agrees. "Discovery biology and chemistry, as practiced in university and industrial labs, is more expensive than it needs to be," Khosla says. "If an organization takes on the challenge of lowering these operating costs without compromising safety and effectiveness, then that is a good thing. I would try it, and would support it, if it worked for me."

The question for researchers will be whether they trust a small startup with their life's work. Some academics believe that completing research tasks by hand connects researchers to their work in an important way. "You'll meet professors who have an allergic reaction to outsourcing research," Byers says. Transcriptic still has to persuade customers that its results are at least as accurate as the ones they would get by hand. Direct comparisons can be difficult, Hodak says, but the company is collecting data to make its case. "Biology is very finicky, and it still takes some work to get a protocol reliable and stable on our platform," Hodak says. "Once it's stable, it requires monitoring and periodic revalidation - but it's vastly more reliable than working by hand."

And among the younger generation, resistance is decreasing, Hodak says. "It's the world's easiest sale to convince a grad student that they want to use this," he says. And if they do, Transcriptic should soon outgrow its single work cell and start building more of them. Already, it's working on a next-generation design. Soon, research may become one more information technology, managed in the cloud instead of the lab. "There isn't a lab in the world that doesn't have more ideas they'd like to test, more hypothesizes they'd like to run," Hodak says. "Because it's very expensive to run even a simple project, and it takes a lot of time, this leads to a lot of weirdness in how decisions gets made on what gets done." Hodak's eyes widen, thinking of all the work his robots will do. "It really changes the field."

are machines and machines are tools. If you use them for extremely precise work, enduring work and otherwise work not doable by humans, you win. If you are a corporation that wants to cut costs and doesn't care about their employees, this is what comes of it.