The graves were discovered during the construction of a roadway near the Polish town of Gliwice, where archaeologists are more accustomed to finding the remains of World War II soldiers, according to The Telegraph.

But instead of soldiers, the graves contained skeletons whose heads had been severed and placed on their legs. This indicated to the archaeologists that the bodies had been subject to a ritualized execution designed to ensure the dead stayed dead, The Telegraph reports.

By keeping the head separated from the body, according to ancient superstition, the "undead" wouldn't be able to rise from the grave to terrorize the living. Decapitation was one way of achieving that; another way was hanging the person by a rope attached to the neck until, over time, the decaying body simply separated from the head.

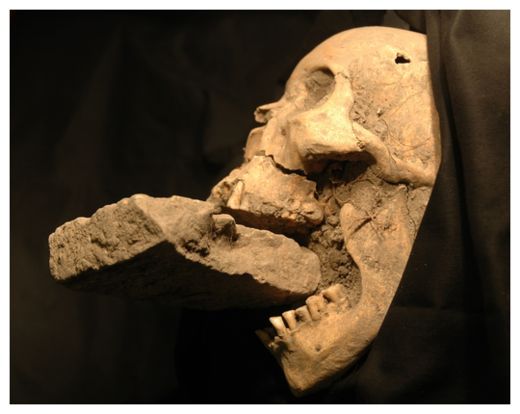

There were other, equally bizarre ways of dealing with vampire burials, according to research published by forensic anthropologist Matteo Borrini. He cites the case of a woman who died during a 16th-century plague in Venice, Italy. The woman was apparently buried with a brick wedged tightly in her open mouth, a popular medieval method of keeping suspected vampires from returning to feed on the blood of the living. The woman's grave might be the earliest known vampire burial ever found.

Hers was a typical case of an accusation of vampirism following some calamity, such as a plague or a devastating crop failure. Accusing an individual of being a vampire was a not-uncommon way of finding a scapegoat for an otherwise unexplained disaster.

In other cases, the body of a suspected vampire might be staked to the ground, pinning the corpse into place with a stake made of metal or wood. In 2012, archaeologists in Bulgaria found two skeletons with iron rods piercing their chests, indicating they may have been considered vampires.

The practice of decapitating the bodies of suspected vampires before burial was common in Slavic countries during the early Christian era, when pagan beliefs were still widespread.

In fact, their belief in vampires stemmed from both superstition about death and lack of knowledge about decomposition. Most vampire stories of history tend to follow a certain pattern where an individual or family dies of some unfortunate event or disease; before science could explain such deaths, the people chose to blame them on "vampires."

Villagers have also mistaken ordinary decomposition processes for the supernatural. "For example, though laypeople might assume that a body would decompose immediately, if the coffin is well sealed and buried in winter, putrefaction might be delayed by weeks or months; intestinal decomposition creates bloating which can force blood up into the mouth, making it look like a dead body has recently sucked blood," writes LiveScience's Bad Science columnist Benjamin Radford. "These processes are well understood by modern doctors and morticians, but in medieval Europe were taken as unmistakable signs that vampires were real and existed among them."

There's no consensus yet on when the bodies found in Poland were buried. According to Jacek Pierzak, one of the archaeologists on the site, the skeletons were found with no jewelry, belt buckles, buttons or any other artifacts that might assist in providing a burial date.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter