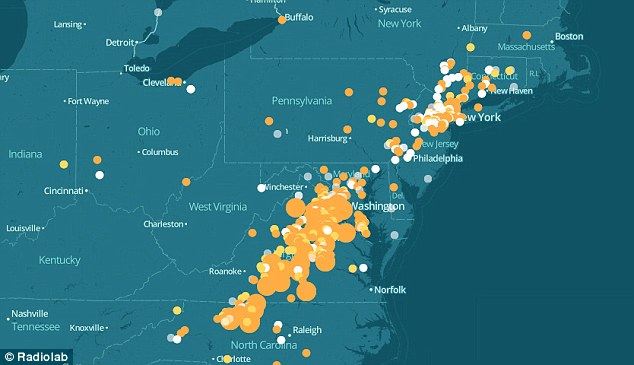

So far the majority of sightings have been in Virginia and other southern states

Further north the weather has been too cool but the emergence of Brood II emergence isn't expected to be too far away

The cicadas invasion of the East Coast has begun, with the insects spotted everywhere from Virginia to Massachusetts.

The infestation, named Brood II by scientists, has not been seen since 1996. Before that it last appeared in 1979.

So far the majority of sightings have been in Virginia and other southern states, where some people have found hundreds in their backyards accompanied by the insects' loud chorus call.

Further north the weather has been too cool in the likes of New England and New York for a full-blown Brood II emergence, but it isn't expected to be too far away.

Cicadas are expected to emerge from the ground in the billions in the next couple of weeks as soil temperature reaches 64 degrees Fahrenheit.

For weeks, bug-watchers have been posting their sightings (and soil temperature readings) to websites such as Cooley's Magicicada.org and RadioLab's Cicada Tracker.

The emergence of the insects has been slower than expected due to this spring's cool temperatures in northern states, reports NBCNews.

In order to bring the soil up to 64 degrees F, air temperatures have to get significantly higher than that on a consistent basis.

The insects are harmless. They do not bite or sting, and will not harm crops or other animals. Lots of people will not even see them, though they could certainly hear their mating call, which was once recorded at 94 decibels.

And the insects can even be transformed into a high protein, low-carb meal.

The magicicadas are only after sex. After a few weeks up singing their loud mating call up in the trees, they will die and their offspring will go underground, not to return until 2030.

Since 1996, this group of one-inch bugs, has been a few feet underground, sucking on tree roots and biding their time.

They will emerge only when the ground temperature reaches precisely 64F.

'This particular brood is extremely large', pest controller Billy Tesh told NBC, who saw a swarm at a farm in Stokes County.

'I've never seen so many in one location in my life. They were on almost every blade of grass.'

A recipe book by scientist Jenna Jadin advocates collecting the creatures for food - though not without consulting a doctor first, and not if you suffer from a nut or shellfish allergy.

She told WUSA9 that about 8pm to 9pm is the prime time for cicada gathering.

'You're going to look at the low-lying shrubs on the ground,' she said.

'You're probably going to need a lot because they're great.'

Ms Jardin, who wrote the book during her PhD at the University of Maryland and now works for the U.S. department of agriculture, advised grabbing the magicicadas off bushes and putting them into a paper bag or basket.

'Newly hatched cicadas, called tenerals, are considered best for eating because their shells have not hardened,' says the book.

'They should be blanched (for 4-5 minutes) soon after collection and before you eat them!

'Not only will this make their insides solidify a bit, but it will get rid of any soil bacteria that is living on or in them. You can then cook with them immediately, or freeze them.'

The insects are expected to arrive in such numbers that people from North Carolina to Connecticut will be outnumbered roughly 600-to-1.

'It's just an amazing accomplishment,' May Berenbaum, a University of Illinois entomologist, told the Associated Press.

'How can anyone not be impressed?'

There are ordinary cicadas that come out every year around the world, but these are different.

They are called magicicadas - as in magic - and are red-eyed. And they are seen only in the eastern half of the United States.

There are 15 U.S. broods that emerge every 13 or 17 years. Last year the swarm affected only a small area, mostly around the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia, West Virginia and Tennessee.

Next year, it is the turn of Iowa into Illinois and Missouri; and Louisiana and Mississippi.

Brood II is one of the bigger groups. Several experts say that they don't know how many cicadas are lurking underground but that 30billion seems like a sensible estimate.

At the Smithsonian Institution, researcher Gary Hevel said it could be closer to a trillion.

If 30 billion magicicadas were lined up head to tail, they would reach the moon and back.

'There will be some places where it's wall-to-wall cicadas,' says University of Maryland entomologist Mike Raupp.

Strength in numbers is the key to cicada survival: There are so many of them that the birds can't possibly eat them all, and those that are left over are free to multiply, he says.

Some scientists think the magicicadas come out in the odd 13 and 17-year cycles so that predators cannot match the timing and be waiting for them in huge numbers.

Another theory is that the unusual cycles ensure that different broods don't compete with each other.

And there's the mystery of just how these bugs know it has been 17 years and is time to come out, instead of 15 or 16 years.

'These guys have evolved several mathematically clever tricks,' Raupp says. 'These guys are geniuses with little tiny brains.'

While they stay underground, the bugs aren't asleep. As some of the world's longest-lived insects, they go through different growth stages and molt four times before ever getting to the surface.

They feed on a tree fluid called xylem. Then they surface, where they molt, leaving behind a crusty brown shell, and grow a half-inch bigger.

The timing of when they first come out depends purely on ground temperature. That means early May for southern areas and late May or even June for northern areas.

The males come out first as nymphs, which are essentially wingless and silent juveniles, then climb on to tree branches and molt one last time, becoming adult winged cicadas.

They perch on tree branches and sing, individually or in a chorus. Then when a female comes close, the males change their song, they do a dance and mate, Raupp explained.

The males keep mating and eventually the female lays 600 or so eggs on the tip of a branch.

The offspring then dive-bomb out of the trees, bounce off the ground and eventually burrow into the earth, he says.

'It's a treacherous, precarious life,' Raupp says. 'But somehow they make it work.'

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter