It's not a question often asked, but perhaps it should be. What did the Druids do for us? The discovery of a road in Shropshire that was built by pre-Roman engineers suggests that indigenous Britons may have been much more accomplished than we - or the Romans - liked to imagine. The road itself tells the story well.

The route had long been known as a lost Roman road, named Margary No 64 after the man who first mapped what everyone assumed to be the country's earliest network. It was visible as a low earthwork and as marks in ploughed fields, and in 1995 archaeologists dug up a bit. Sure enough, it looked Roman.

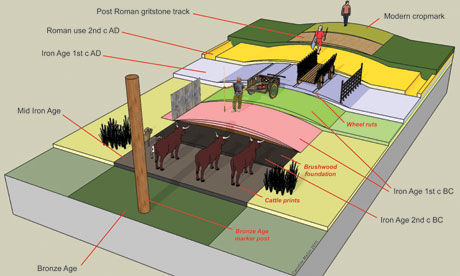

But in 2009, quarrying by Tarmac was due to destroy 400m of it, giving archaeologists a rare opportunity to expose a long section of road, some of it, crucially, very well preserved. At first, it still looked Roman, from its cambered, cobbled surface on a metre of hardcore and a clay base, to the ditches at the sides with a thin scatter of Roman rubbish. However, dig director Tim Malim noticed that the road had twice been rebuilt, and knew its history could be dated using a technique that tells you when buried mineral grains were last exposed to sunlight.

The unexpected result was a more than 80% chance that the last surface had been laid before the Roman invasion in AD43. Wood in the foundation was radiocarbon-dated to the second century BC, sealing the road's pre-Roman origin. And Malim thinks a huge post that stood in 1500BC close to the crest of the hill was a trackway marker.

So, while the cobbles rattled to the sound of carts and chariots generations before the Romans invaded Britain, the route itself was older than Rome.

When the Roman army marched around its new conquest, it was not above using the road and discarding its litter. Indeed, there's every reason to believe that the Shropshire road continues north to meet Watling Street, suggesting that one of the Roman engineers' great achievements was at least in part no more than an act of resurfacing.

It is fashionable among archaeologists and ancient historians to debate how much Britain was really "Romanised". There is no consensus. But notwithstanding villas with central heating and public statues of Roman emperors, some academics portray the four centuries of Roman occupation as a mere ripple on the longer and stronger flow of native culture and politics.

But what of the reverse? Could Britain have been more "Roman" than was thought, before it was invaded? What do we find if we follow route 64 back into the past?

The road implies not just the ability to design and organise its construction, but also the justification for its cost - heavy traffic. Immediately we are outside a vision of ancient Britain where wheeled vehicles appear only in battle, as Roman writers would have it, in chaotic displays of chariotry.

Archaeological evidence is clear that long before the Roman invasion, the British landscape was well organised, with a dense network of fields and tracks. Larger settlements were towns in all but name, where homes were separated from industrial areas by streets, and functions such as mass storage and ritual had their separate places. Baths, medicines, skilled arts and crafts, perhaps even forms of currency - such things were commonplace, and can be seen evolving over millennia.

But archaeology is revealing a twist to this native sophistication, which suggests that before they were invaded, Britons were more aware of Rome than Rome was of Britain. This is seen no more clearly than in a cemetery near Colchester, Essex, excavated mostly in the 1990s at, as it happens, another Tarmac quarry.

Some very special people had been buried there. They weren't leaders, but members of the ruling class who had died between about AD40 and AD60: it's conceivable that some of them actually saw the invading Roman army, but they had grown up and learned their skills long before. There is nothing about their graves that looks in the least bit Roman. One of the men could have been a druid.

But when you look at the things the deceased took with them, you notice a striking thing: Rome. Or more specifically, precious Roman objects requiring Roman expertise. These include a beautiful blue glass jar of a type more typically found in the Mediterranean region around the time of the birth of Christ, that probably held a cosmetic. There is a pottery inkwell: did its owner write? One man took with him a large Italian wine jar and a copper jug and basin set, such as was common in Pompeii; an amber-coloured glass bowl may have been made in Italy.

And then there is "the doctor". This man had his wine jar, his imported pottery service and copper vessels. But he also had a set of surgical instruments - one of the oldest known in the ancient world. The tools are recognisably functional - scalpels, forceps, probes and more - and comparable to finds made around the Roman empire.

But they are not Roman. On current evidence, they were made in Britain to designs that merely borrowed from Greece and Italy. Buried with the surgeon's shiny tools were divining rods and a magical board game. Whether you call him a doctor or a druid, he was a local aristocrat with access to luxuries and ideas from Rome and beyond, and he had the ability to choose.

Archaeology traditionally deals in centuries; history in years. If you find something that looks Roman, you will probably call it Roman, though the dating may be too imprecise to pin down your discovery to a generation, still less a few years either side of a historical event such as a military invasion. Many things here once thought "Roman" could, in fact, be older. Shropshire's road, then, could be the start of a journey that changes the way we think about early Britain.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter