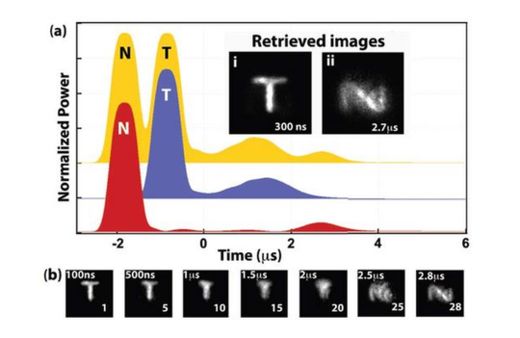

The physicists used lasers and a magnetic field to store the letters "N" and "T" as separate images in a small container filled with rubidium atoms. Then they hit the metaphorical replay button - reversing the magnetic field so that the atomic vapor reemitted the images of the letters as light signals. The very short movie plays with just one millionth of a second between the two images.

"It is very exciting because images and movies are familiar to everyone," said Quentin Glorieux, a physicist at the Joint Quantum Institute of the National Institute of Standards and Technology." We want to go to the quantum level."

The storage achievement goes far beyond a scientific parlor trick. Glorieux and his colleagues hope to harness the storage method for superfast quantum computers that would operate based on the strange, "spooky" behavior of particles at very small scales.

Such quantum memory storage uses a process pioneered at the Australian National University, called gradient echo memory (GEM). In this case, the GEM storage method involved a cell almost 8 inches (20 centimeters) long filled with the rubidium atomic vapor.

"If we manage to store quantum information embedded in an image or maybe in multiple images, that could really hasten the advent of a quantum network/internet," Glorieux said.

But the physicists have a lot of work ahead to make the method useful. The atomic vapor always runs the risk of dispersing and ruining the image, so that longer storage times lasting just 20 microseconds (1 microsecond being one millionth of a second) led to fuzzier images.

If that all sounds confusing, an enterprising musician turned the paper's description into a catchy Internet song that is waiting to go viral on YouTube. His efforts have drawn praise so far - one comment (supposedly from an author of the physics paper) invited the musician to "read-sing all of our work from now on" to make it more friendly for general audiences.

"We studied the storage and retrieval of images in a hot atomic vapor (hot, hot, hot)," sings YouTube user "therockcookiebottom."

"This is the future, oh yeah!"

The paper is published in the May 21 issue of the Journal Optics Express.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter