The Oakland man has a willing donor and private insurance to pay for the transplant. But he faces what may be an insurmountable hurdle in the race to save his life: He is an illegal immigrant.

Administrators at UC San Francisco Medical Center are refusing to transplant a kidney from Navarro's wife, saying there is no guarantee he will receive adequate follow-up care, given his uncertain status.

Their decision is a stark illustration of the tension between health care and immigration policies in the state and underscores the difficult role medical professionals play in trying to save the lives of undocumented residents.

Though no data are available, anecdotal evidence suggests clinics sometimes perform organ transplants on illegal immigrants, especially when the patients are young. In one high-profile case, UCLA Medical Center gave an undocumented woman three liver transplants before she turned 21.

But health administrators also reject patients because of their immigration status, though that usually happens when the patients lack insurance. Bellevue Hospital in New York attracted attention last year when it refused to transplant a kidney between brothers because they could not pay for the operation.

It is the kind of ethical gray area that hospitals hate, said University of Pennsylvania bioethics professor Arthur Caplan.

"It puts the doctors in a very awkward and torn position," he said. "You come into this trying to do good and find yourself stuck in the middle of a fight about immigration."

Immigrant advocates and some scholars say it is wrong for hospitals to withhold health care from the seriously ill, no matter their legal status.

But proponents of tougher border enforcement -- and those fighting to contain ballooning health care costs -- fear that providing such services could lure more undocumented immigrants.

Matter of survival

Navarro, 35, never thought his survival would hinge on his immigration status. He has had private insurance through Berkeley's Pacific Steel foundry for 14 years.

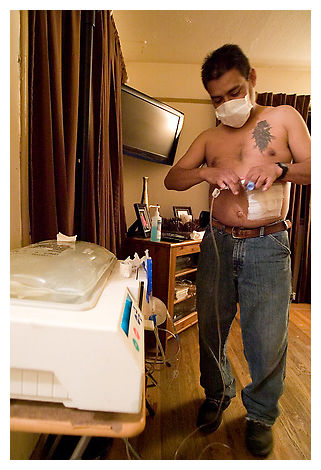

When his kidneys began to shut down eight years ago, he continued to work full time. Each evening, he would cleanse his blood of lethal toxins using a home dialysis machine. But the soft-spoken metalworker has been growing sicker. Life expectancy for dialysis patients hovers around six years.

This spring, the family got a call from UC San Francisco's transplant center: Navarro had reached the top of the waitlist.

"We were so happy," recalled his wife, who went with him for the final work-up.

But in their final consultation before the surgery, Navarro said doctors discovered his immigration status and called off the operation.

"I started crying and crying and crying," said his wife, who asked that her name be withheld because she is also in the country illegally. She offered her own kidney -- and was a match -- but administrators again said no.

UC San Francisco declined to comment on Navarro's case, but Reece Fawley, executive director of transplantation, said in a statement that the clinic evaluates all patients for socioeconomic stability.

"UCSF's policy for financial clearance requires candidates to present evidence of adequate and stable insurance coverage or other financial sources necessary to sustain follow-up care long after transplant surgery," she said. "Immigration status is among many factors taken into consideration."

Navarro was caught up in an immigration audit and lost his foundry job this month. His private insurance continues for now, and he is trying to extend it. But he may end up in the state's Medi-Cal program.

That would deepen Navarro's dilemma. Though Medi-Cal will cover his daily dialysis -- which costs $17,000 a month -- because of his illegal status, it will not pay for the immunosuppressive drugs that ward off organ rejection. The drugs cost $20,000 annually. Medi-Cal also won't pay for organ transplants for illegal immigrants.

No guarantees

The hospital won't perform the transplant without a guarantee that the drugs and accompanying treatment will be paid for.

Some bioethicists say the hospital should have performed the surgery because Navarro would not be taking resources away from other patients or putting his wife at serious risk.

After all, many legal residents fail to follow their post-surgical plan.

"Why was this patient denied the opportunity to comply?" asked Santa Clara University bioethics professor Margaret McLean.

Other experts suggest that the possibility of saving a life should outweigh concerns about follow-up care.

"He has the organ -- the critical resource -- if he can get it transplanted," said University of Southern California bioethics professor Michael Shapiro. "That's a serious chance at life."

But critics say that providing any long-term care to illegal immigrants is irresponsible and discourages home countries from investing in an adequate health system.

"You just cannot provide care for illegal aliens without getting into uncompensated care," said Bob Dane of the Federation for American Immigration Reform.

Navarro said his chief concern is finding a job, not the quest to save his life. But he worries for his family and takes anti-anxiety pills to sleep.

If transplant doctors working with illegal immigrants are in a bind, so are the Navarros.

"We don't know what to do," said Navarro's wife, watching her husband chase their 3-year-old daughter. "It's like we're on a ledge -- we can't go here or there."

Reader Comments