Archaeological sites are often in remote and rugged areas. As such, it can be hard to reach and map them with the limited budgets archaeologists typically have. Scientists are now using drones to extend their view into these hard-to-reach spots. "There are a lot possibilities with this method," said researcher Marijn Hendrickx, a geographer at the University of Ghent in Belgium.

The machine tested in a remote area in Russia called Tuekta was a four-propeller "quadrocopter": the battery-powered Microdrone md4-200. The fact it is small ? the axis of its rotors is about 27 inches (70 cm) ? and weighs about 35 ounces (1,000 grams) made it easy to transport, and researchers said it was very easy to fly, stabilizing itself constantly and keeping at a given height and position unless ordered to do otherwise.

The engine also generated almost no vibrations, they added, so that photographs taken from the camera mounted under it were relatively sharp. Depending on the wind, temperature and its payload, the drone's maximum flight time is approximately 20 minutes. [Drones Gallery: Photos of Unmanned Aircraft]

Tuekta is in the Altai Mountains where Russia, China, Kazakhstan and Mongolia come together. Researchers there have discovered burial mounds 2,300 to 2,800 years old and up to 250 feet (76 meters) wide.

These burial mounds, called "kurgans," probably belonged to chiefs or princes among the Scythians, a nomadic people known for their horsemanship, who once had a rich, powerful empire. Excavations of some of these have revealed extraordinary treasures of gold and other artifacts well-preserved by permafrost.

Nearly 200 burial mounds were discovered in Tuekta, situated along the River Ursul. The site's heart appears to once have been a row of five monumental Scythian burial mounds with diameters between 140 and 250 feet (42 and 76 m). Regretfully, "in this study area, most of the burial mounds are destroyed," Hendrickx said.

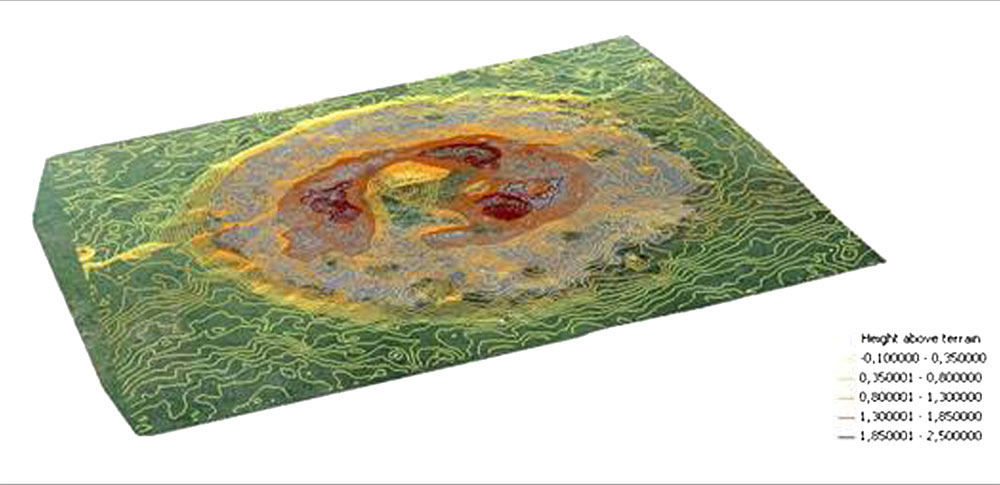

The test area the researchers chose measured approximately 1,000 feet by 330 feet (300 by 100 m), including the five giant mounds and dozens of smaller structures. They flew the drone at a height of 130 feet (40 m) to study one mound in greater detail.

The lightweight nature of the microdrone was a problem at times. "In the field we had to deal with rising wind," Hendrickx recalled. "At some point we even lost the radio connection with the drone - this led to a sprint between the kurgans."

"The 3-D model we created gives us the possibility to calculate the volume of the kurgan," Hendrickx told LiveScience. "With this volume and its precise dimensions, the original shape of the kurgan can be reconstructed."

Archaeologists have begun to use airborne drones more often in the past decade or so, including in Peru, Austria, Spain, Turkey and Mongolia. The resulting maps can help archaeologists see the big picture of a site where up-to-date aerial or satellite images are hard to get, Hendrickx said. [10 Modern Tools for Indiana Jones]

The researchers are now experimenting with a larger microdrone that can carry more weight.

"This will make it possible to use, for instance, infrared cameras or even a radar system," Hendrickx said. "This can make it possible to see things we can't see with our eyes."

The scientists detailed their findings in the November issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science.

...but if we don't also cultivate parallel spiritual abilities, we could get caught with our pants down.

These technologies cost money. That means they will be used mostly by capital, for the purposes of capital. I'm thinking surveillance, remote "removal" of "troublesome" persons, etc.

It also costs time and money to develop spiritual abilities. But probably less than just one fancy remote-controlled explorer robot. And it's the only "low-tech" hope the rest of us have to keep up with the high-tech games the wealthy groups are playing.

So if we work on this, be may be able to maintain a "balance of powers" so to speak. The subject of rehabilitating our spiritual powers is also in its infancy on this planet. Let's not neglect it! It could save us all some day.

And why bother with radio-controlled quadrocopters when you can just go exterior and look for yourself?