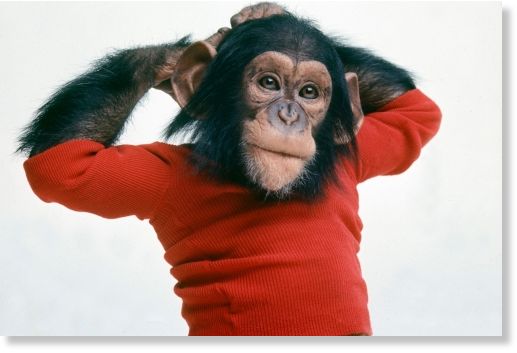

© Harry BensonNim Chimpsky, as seen in Project Nim.

Project Nim,

in theaters Friday, chronicles a bizarre 1970s project that sought to teach chimpanzees language. Marlow Stern spoke with the Oscar-winning filmmaker James Marsh about the ape It's been almost 80 years since King Kong dangled Fay Wray from the Empire State Building, but once again, simian cinema is all the rage in Hollywood. There's the Kevin James comedy

The Zookeeper, featuring a gorilla voiced by Nick Nolte, and later this summer the ubiquitous James Franco, not to be outdone, will square off against a legion of apes imbued with human-like intelligence in the blockbuster

Planet of the Apes prequel,

Rise of the Apes. And, outside of the "high concept" Hollywood kingdom, there's

Project Nim, the latest documentary from James Marsh, who won an Oscar in 2008 for his awe-inspiring film about Philippe Petit's high-wire balancing act between the Twin Towers,

Man on Wire.

"It's one of those things that you don't know when you set out on a film two years ago where it will end up in the culture and the zeitgeist," said Marsh. "I heard the same thing about

The Dark Knight and

Man on Wire. Take your pick, in a way. Ours is true, ours happened, and you see real human emotions in that, and real animal emotions in that."

Based on Elizabeth Hess' book

Nim Chimpsky: The Chimp Who Would Be Human, Marsh's film uses a combination of interviews, archival footage, and reenactments to tell the tale of Nim Chimpsky, a chimpanzee who was the subject of a study led by Columbia University Prof. Herbert Terrace, that attempted to prove if an ape was raised like a human, it could develop language skills. The ape's name was sly nod to Noam Chomsky, the renowned language theorist who posited that only humans could embrace language. "Personally, I never really felt that the project had much chance of success, and didn't follow it closely," Chomsky told

The Daily Beast. "I don't see much point trying to raise humans to act like apes, or conversely."

Prof. Terrace separated Nim from his mother, and the family of one of his former students (and lovers), Stephanie LaFarge, raised the baby chimp in an apartment on Manhattan's Upper West Side. It was a bizarre setup from the start, and one plagued by unpreparedness. "Stephanie took over at the beginning, but I was led to believe that she was going to do a different job than she did," said Prof. Terrace. "When she got him, she just decided she was going to have fun with Nim." LaFarge was first playful, and then began breastfeeding Nim, and as he got older and more sexually curious, as all adolescents do, even allowed the chimpanzee to fondle her breasts. "Stephanie's attempt at mothering him was based on being a human mother, and she reproduced some of that in her own way," Marsh chuckled.

Upset by the lack of progress in the study, and worried by Nim's growing size and aggression--he attacked Stephanie several times--the chimp was moved from Stephanie's brownstone to a sprawling estate in Riverdale owned by Columbia University. Terrace enlisted new caretakers for Nim, including Laura-Ann Pettito, who managed to teach Nim a number of signs through sign language. "If you show weakness in their presence, they'll dominate you," said Marsh. "It seems counterintuitive for [Laura] to slap him around, but that's actually the best way of showing him that you're in charge." The chimp would eventually learn 125 signs and become a star of sorts, appearing on the covers of

New York magazine and

High Times, thanks to a habit of smoking joints that it picked up from the DeFarges. "Chimpanzees like drinking alcohol and smoking pot, and we heard stories of some in Oklahoma liking ketamine, so they have impulses for the altered states," said Marsh. "It's an interesting insight - that chimps like thrills and sensations for their own sake, like we do."

After viewing a tape of Nim signing to a teacher, Terrace came to the conclusion that Nim was merely imitating the signs given to him, and could not sign without some sort of prompting. "I realized that language was out of their realm, and the only reason that they sign was to obtain various rewards," said Terrace. "Some may say it's a failure, but I think it's a positive in as far as we define what it's like to be human, and how we anthropomorphize about animals, and our relation to them." He pulled the plug on the entire experiment and, in 1977, transferred Nim, now a grown ape, to the Institute for Primate Studies at the University of Oklahoma, where it could finally cohabitate with other apes. There, Nim met Bob Ingersoll, a high-spirited University of Oklahoma student who worked at the facility. "My main function was to take people out on walks with chimps - famous people, mostly," said Ingersoll. "Michael Crichton came out there once, and if you read

Congo, Roger [an ape there] is actually one of the fictionalized characters in the book."

Ingersoll, a longhaired hippie, and Nim built a special bond thanks to their mutual love for (excuse the expression) "monkeying around" in the woods - running, sliding down trenches, climbing up trees, etc. - and eventually became best friends. "Back then, I was 125 lbs. tops, so there was no way I was going to dominate a chimp," said Ingersoll. "It has to do with trust, certainty, and familiarity. The chimp has to be certain of what you're going to do, and has to be familiar of how you act in order to play off you." The two also shared a love of marijuana, and would sometimes go out and smoke joints together in the woods. "They seem to like being stoned, and to be fair to Bob, it chills them out," said Marsh. "Like people, they don't tend to go and beat up one another when they're stoned, and neither did Nim."

The institute's money soon began running dry, and the university had no choice but to transfer Nim to New York University's LEMSIP - the Laboratory for Experimental Medicine and Surgery in Primates - in Tuxedo, New York, where Nim became the subject of

animal testing, providing some of the film's most chilling moments. A campaign was then spearheaded by Ingersoll to save Nim, and after dozens of letters, his voice was heard. The Black Beauty Ranch in Texas, operated by The Fund for Animals, purchased Nim, and created a custom, caged living environment for him. There, Nim lived out the rest of his days, dying in 2000 at age 26 from a heart attack.

"The whole experiment is framed as a nature-versus-nurture idea, and that's how Nim's life becomes his tragedy," said Marsh. "His nature is a powerful force that can't be inhibited by human constructs."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter