Don't tell Hollywood. Or Bill Keller's agent. At latest count, at least four studios are working on at least five movies about the WikiLeaks story. And with Assange somewhat out of pocket while on house arrest, plenty of option deals are going to journalists who are covering the secretive organization.

- Guardian reporters David Leigh and Luke Harding sold rights to their book WikiLeaks: Inside Julian Assange's War on Secrecy to DreamWorks

- Raffi Khatchadourian embedded with Assange for a New Yorker profile and sold rights to his HBO and the BBC which will release a documentary by Inside Job director and Oscar winner Charles Ferguson.

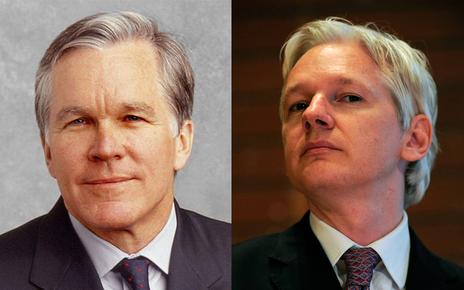

- Bill Keller sold his life rights to a production company led by another Oscar winner, Mark Boal, writer/producer of Hurt Locker, after he wrote about his dealings with Assange.

The flurry of deals has made it difficult for some journalists to report on a story that now involves their peers. When Frontline, which produces investigative films for US public TV, interviewed two Guardian journalists for its WikiSecrets programme, it was told it could use only limited footage because the reporters were under contract with another production.This, of course, is hardly the first time journalists have optioned an article or book. Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein became millionaires off of their book, All the President's Men, and the resulting movie starring Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman. In fact, Redford reached out to Woodward and Bernstein while they were still reporting on the scandal to make their reporting efforts into a detective film. "I thought that would make it a better movie because history would provide the answer, and it was going to be a very big answer, said Redford at the 35th anniversary of the films release this April. "It was never about what the public knew; it was about what the public didn't know."

"What's awkward is that these guys were journalists, but they were also players [in the story]," said Martin Smith, who produced WikiSecrets. "The idea that companies can buy people out of stories gets in the way of reporting."

One could argue, however, that reporting on the Watergate scandal was yesterday's news by the time Woodward and Bernstein released their book in 1974. (The movie version followed in 1976.) However, WikiLeaks is a different kind of story. With thousands of documents and diplomatic cables not yet released, The Guardian, The New York Times and other news organizations will likely be sourcing WikiLeaks material for some time to come. Does it seem less than ethical for newspapers to profit off of their relationship with WikiLeaks while still reporting on WikiLeaks?

Based on past statements about his relationship with his sources at WikiLeaks, Keller may leave it to others and history to decide. "Deep Throat had an agenda. Ellsberg had an agenda," Keller told the Poynter Institute in regards to a survey last year about how WikiLeaks is changing the power structure of news organizations. "That doesn't invalidate the information they provide us. If we refused to work with sources whose motivations we didn't share, a lot of important stories would go untold ... The critical thing is what we do with the material--check its authenticity, draw our own conclusions from it, put it in context, and lay it all out for readers on our terms, not the source's terms."

"Awkward" might be the best word to describe the path forward. Keller, at least, will play less of a role in Times reporting on WikiLeaks when he steps down as executive editor in September. Further, the depiction of Keller's involvement with Assange in upcoming films will presumably only cover past events. Whether rising executive editor Jill Abramson will let him report on WikiLeaks is yet to be determined, and it may serve as a nice epilogue. We can see the scene now. Justin Timberlake as Keller, Natalie Portman as Abramson. A white-haired Jesse Eisenberg lurking in the background. "I believe I deserve some recognition," he says quietly.

Wait, somebody already thought of this approach.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter